In sixth grade sophomore Zachary Willmore said he knew he was gay when he memorized all the lyrics to Nicki Minaj’s “Super Bass.” While he doesn’t watch sports often, he said Minaj is the closest person he knows to a professional athlete because she “puts that thing in sports,” a reference to the artist’s song “MotorSport” with Migos and Cardi B.

In seventh grade Willmore came out through a PowerPoint presentation in front of his entire social studies class and said he received no negative responses.

“I was lucky in that way because I know that a lot of people don’t get very much positive feedback,” Willmore said, “but my friends, family and teachers were all very supportive of me, and my social studies teacher at the time made rainbow cookies for everyone after the presentation.”As a varsity cheerleader who started gymnastics in eighth grade, Willmore said having coaches and athletic peers support LGBTQ team members is important. He said regardless of how an athlete identifies, he or she can have “great talent and potential.” With a supportive and accepting environment, Willmore said LGBTQ athletes can thrive.

“My coaches and team mates have been incredibly supportive, and the main thing about them being supportive is that me being gay isn’t a big deal,” Willmore said. “It never really gets brought up, and I just feel like a regular part of the team instead of just the ‘gay one.’” Middle school was a formative time for junior Piper Forthaus, as well. She came out to her friends and family as bisexual in eighth grade and said her family had “no major reactions.”

“Figuring out my identity was a weird process,” Forthaus said. “At first I thought I was gender queer, and then gay and then I realized it was [definitely] bisexuality, but I think everyone goes through those stages, so it’s different for everyone but a common experience.”

The most supportive person in her life, Forthaus said, has been her older brother. He, too, is bisexual and came out after Forthaus. She said he is her role model and one of her closest confidants. She said he helped her learn about his journey as well as her own.[TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Container hotspot_image=”323860″][TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Single hotspot_title=”Safety of LGBTQ youth” hotspot_positions=”21,17″ hotspot_color_dot=”#ffffff” hotspot_color_circle=”#b53859″ hotspot_color_pulse=”#b53859″ content_tooltip_title=”LGBTQ youth report” content_tooltip_content_html=”JTNDcCUzRSUyMjgwJTIwcGVyY2VudCUyNm5ic3AlM0JvZiUyMExHQlElMjB0ZWVuYWdlcnMlMjBhbmQlMjZuYnNwJTNCODMlMjBwZXJjZW50JTIwb2YlMjB0cmFuc2dlbmRlciUyMHRlZW5hZ2VycyUyMGFyZSUyMG5vdCUyMG91dCUyMHRvJTIwdGhlaXIlMjBjb2FjaGVzJTJDJTIyJTIwYWNjb3JkaW5nJTIwdG8lMjB0aGUlMjBIdW1hbiUyMFJpZ2h0cyUyMENhbXBhaWduJTIwRm91bmRhdGlvbiUyMGFuZCUyMHRoZSUyMFVuaXZlcnNpdHklMjBvZiUyMENvbm5lY3RpY3V0JTIwcmVwb3J0JTJDJTIwJTNDZW0lM0VQbGF5JTIwdG8lMjBXaW4lM0ElMjBJbXByb3ZpbmclMjB0aGUlMjBMaXZlcyUyMG9mJTIwTEdCVFElMjBZb3V0aCUyMGluJTIwU3BvcnRzLiUzQyUyRmVtJTNFJTIwTGVzYmlhbiUyMGZsYWclMjBhbmltYXRpb24lMjBieSUyMFNub3d5JTIwTGkuJTNDJTJGcCUzRQ==” content_tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-right”][/TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Single][/TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Container]“He was the first person I told, so we kept it on the low because I was nervous about my parents before I knew they were chill about it,” Forthaus said.

While Forthaus has been swimming competitively for six years and is a member of the RBHS swimming and diving team, her brother was a dancer at the Columbia Performing Arts Center. Forthaus said because her brother is a male dancer, outsiders assumed he was gay before he began contemplating his own sexual orientation. While Forthaus told certain people about her sexual orientation on her own terms, she said her brother’s journey was “a lot more pressured and publicized” because of people’s more openly judgmental attitudes.“Siblings are a real gift, especially when they’re in a similar situation,” Forthaus said. “He’s just been a rock for me and all of my issues.”

All in all, Forthaus said she’s had a mostly positive experience coming out. She described her mixed-gender swim team as misogynistic, though, so she wasn’t sure if she could “come out to everyone all at once” and instead elected to only tell certain teammates whom she felt comfortable with.

“As an athlete, coming out to my team felt like broadcasting it just to be like, ‘I’m different,’” Forthaus said, “so it was very, like, low-key and only close people really.”

Dr. Brian Brown is the Deputy Athletics Director at the University of Missouri ― Columbia (Mizzou). In addition to his position in the athletic department, Dr. Brown is the coordinator for Student-Athletes Fostering Equality (S.A.F.E.), a group that focuses on education and intentional dialogue surrounding real-world issues including those in the LGBTQ community. Within workplaces, academic institutions and athletic programs, Dr. Brown said all people should feel welcomed, valued and respected regardless of their race, gender, sexual orientation or background, and creating such an environment starts with education.

“We’re fostering, I guess, a safe environment where you can have vulnerability around these discussions [about the LGBTQ community] because they don’t naturally happen in the locker room,” Dr. Brown said. “They don’t naturally happen unless there’s a classroom focused on that particular topic.”

By promoting respect and encouraging cultural competency, Dr. Brown said people can educate themselves on how to thoughtfully learn and listen. Putting everyone in the same box or providing a blanket resource for all marginalized people, thus ignoring the various groups’ inherent differences, would not necessarily meet each group’s specific needs, Dr. Brown said. For example, a racial minority and a religious minority may experience overlap in their needs, but support with the intention of helping one group could prove ineffective in aiding the other. Allies can thus understand what to say and not to say so as to prevent unintentional harm and become more sensitive and empathetic supporters of underrepresented groups.

“Sometimes people just want to not be stereotyped or pointed out. They just want to have their own safe existence as opposed to [being] labeled any particular group,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s tricky, but you just start off by just being good, moral people who respect everyone and be willing to listen more than anything.”

Athletes urge coaches, leaders to promote acceptance

Forthaus said coaches need to create inclusive environments, making sure athletes know they belong on a team or in a sport. The LGBT SportSafe Inclusion Program exists to educate people of authority (such as coaches and administrators) at all levels of athletic competition on how to protect and support LGBTQ athletes, according to the program’s website. LGBT SportSafe reported 84% of athletes “witnessed or experienced homophobia in sports” and said LGBTQ student-athletes “generally experience a more negative climate than their straight peers,” which can be detrimental to their academic success and athletic identities.[TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Container hotspot_image=”323857″][TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Single hotspot_title=”How to be an ally to the LGBTQ community” hotspot_positions=”21,17″ hotspot_color_dot=”#ffffff” hotspot_color_circle=”#70267c” hotspot_color_pulse=”#70267c” content_tooltip_title=”How to be an ally to the LGBTQ community” content_tooltip_content_html=”JTNDcCUzRSUyMkJlbGlldmUlMjB0aGF0JTIwYWxsJTIwcGVvcGxlJTJDJTIwcmVnYXJkbGVzcyUyMG9mJTIwZ2VuZGVyJTIwaWRlbnRpdHklMjBhbmQlMjBzZXh1YWwlMjBvcmllbnRhdGlvbiUyQyUyMHNob3VsZCUyMGJlJTIwdHJlYXRlZCUyMHdpdGglMjBkaWduaXR5JTIwYW5kJTIwcmVzcGVjdCUyQyUyMiUyMGFjY29yZGluZyUyMHRvJTIwR0xBQUQuJTIwQXNleHVhbCUyMGZsYWclMjBhbmltYXRpb24lMjBieSUyMFNub3d5JTIwTGkuJTNDJTJGcCUzRQ==” content_tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-right”][/TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Single][/TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Container]“If my coaches/other athletes were not as accepting I probably would’ve been more inclined to quit,” Forthaus said. “I think in general women are more accepting, and if I had been in a more traditionally anti-gay sport it would’ve been harder. I probably would’ve pretended to be straight.”

Although Willmore had a positive experience and said his coaches and teammates were “extremely supportive” and helped him grow as a person as well as an athlete, not all LGBTQ athletes share this story. LGBT SportSafe reported 85% of athletes have “received verbal slurs,” and 70% of athletes “find homophobia worse in sports than society.”Willmore said as the media continues to change by showing increased diversity, inclusion, acceptance and equality on television and in films, the more coming out will become a cultural norm, even for LGBTQ athletes. While he said he doesn’t want to be celebrated simply because he is gay, pride marches and Pride Month in June exist to help make societal changes and normalize LGBTQ identities.

“If my coaches and teammates were not supportive of my me being gay, I would have finished the year and not tried out again,” Willmore said. “I would understand that not everyone can be accepting, but I wouldn’t want to surround myself with those people.”

When leaders do not keep the well-being of youth intentionally in their hearts, Dr. Brown said the strength of a community becomes weaker. Through the stop-start continuum he uses during S.A.F.E. meetings, Dr. Brown asks participants to help him identify what changes need to be made to Mizzou’s athletic department and campus environment to better support LGBTQ people. Dr. Brown said he wants people to treat one another with respect, integrity, gratitude and humility to create community, part of the athletic program’s “Win it Right” philosophy of accountability.

“Like any underrepresented group, if there’s not value shown, there’s not some intentionality, you lose the strength of that community because that group then feels marginalized, voices not heard and we would reinforce bigotry, and we would compromise the ability to have anyone feel really welcome and valued,” Dr. Brown said. “So you would lose a part of that community that I think … makes you stronger.”

As for people and programs who haven’t made progress toward inclusivity, Forthaus said she thinks they are scared of the backlash they’ll receive, and the only reason they won’t take the necessary steps to create a more accepting environment is “because they’re afraid they’ll lose revenue from their typical audience.”

The Center for American Progress (CAP) conducted a study using an online sample of adults to “explore the public’s beliefs about professional sports teams that support LGBT issues.” Of all respondents, 56.1% said their opinion of a professional sports team would become “significantly more positive” or “somewhat more positive” if the team “expressed support for LGBT athletes and fans;” this support crossed gender lines as 54.5% of men and 57.3% of women responded with the same two positive answers, according to the CAP survey.“Like any underrepresented group, if there’s not value shown, there’s not some intentionality, you lose the strength of that community because that group then feels marginalized, voices not heard and we would reinforce bigotry, and we would compromise the ability to have anyone feel really welcome and valued,” Dr. Brown said. “So you would lose a part of that community that I think … makes you stronger.”

As for people and programs who haven’t made progress toward inclusivity, Forthaus said she thinks they are scared of the backlash they’ll receive, and the only reason they won’t take the necessary steps to create a more accepting environment is “because they’re afraid they’ll lose revenue from their typical audience.”

The Center for American Progress (CAP) conducted a study using an online sample of adults to “explore the public’s beliefs about professional sports teams that support LGBT issues.” Of all respondents, 56.1% said their opinion of a professional sports team would become “significantly more positive” or “somewhat more positive” if the team “expressed support for LGBT athletes and fans;” this support crossed gender lines as 54.5% of men and 57.3% of women responded with the same two positive answers, according to the CAP survey.“All people should be accepted in sports because anyone can play,” Forthaus said, “and the culture of sports prior to these movements doesn’t make it seem that way.”

Forthaus said she thinks the negative perception of LGBTQ athletes comes from the fans, as well as some athletes. She said there is a common stereotype that members of the LGBTQ community are “less committed or worse at the sport” or are only there to meet cute people. A couple times, Forthaus said other people told her she had “better not be looking at them in the locker room,” making the incorrect assumption that because she is attracted to males and females she must be attracted to everyone.

“I tried not to let it get to me and never really talked about anything relating to my sexuality, and it was fine,” Forthaus said. “I loved the sport, and I wanted to continue swimming, so I made sure to just tailor my words to those around me and not make it a point to tell new members of the team or people I hadn’t told before.”

Positive role-models, sincere allyship set example for future

By looking at historically marginalized groups and their experiences, Dr. Brown said it is clear at some level all underrepresented groups are suffering from a lack of access, stereotypes and bigotry. There may not be a way to entirely eliminate all forms of bigotry in an instant, but by identifying and creating success stories, Dr. Brown said the people who are bigots become outliers. Changing a culture takes time, and he said people must be willing to get their hands dirty and dig into an issue to make lasting, positive change.

“From a mental approach, if you don’t feel valued by your teammates or by your peers, it could affect your athletic ability,” Dr. Brown said. “It could affect your approach to games. It could affect your life.”

In the future Forthaus hopes to see openly LGBTQ players in male professional sports leagues because that’s where she thinks the greatest change can happen. As a hockey fan herself, Forthaus said she sees and hears slurs become insults to call out other teams. She said the culture of sports needs to be re-evaluated, and fans need to educate themselves on what being an LGBTQ person means, even if they themselves don’t identify as part of the community. [TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Container hotspot_image=”323862″][TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Single hotspot_title=”Accessible resources for LGBTQ athletes from the NCAA” hotspot_positions=”21,17″ hotspot_color_circle=”#efd94a” hotspot_color_pulse=”#efd94a” content_tooltip_title=”Accessible resources for LGBTQ athletes from the NCAA” content_tooltip_content_html=”JTNDcCUzRSUyMkF0aGxldGljcyUyMGRlcGFydG1lbnRzJTIwc2hvdWxkJTIwbWFpbnRhaW4lMjB1cC10by1kYXRlJTIwTEdCVFElMjBpbmNsdXNpb24lMjByZXNvdXJjZXMlMjB0aGF0JTIwYXJlJTIwcmVhZGlseSUyMGF2YWlsYWJsZSUyMHRvJTIwY29hY2hlcyUyQyUyMHBsYXllcnMlMjBhbmQlMjBzdGFmZiUyMHRocm91Z2hvdXQlMjB0aGUlMjB5ZWFyJTJDJTIyJTIwYWNjb3JkaW5nJTIwdG8lMjB0aGUlMjBOQ0FBLiUyMFBhbnNleHVhbCUyMGZsYWclMjBhbmltYXRpb24lMjBieSUyMFNub3d5JTIwTGkuJTNDJTJGcCUzRQ==” content_tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-right”][/TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Single][/TS_VCSC_Image_Hotspot_Container]Growing up in Columbia was a “weird area to be out in,” Forthaus said because of the strange intersection between its relatively large size and Midwestern culture. She said she didn’t know any other LGBTQ athletes aside from one other swimmer, and both of them shared similar experiences in the sport.

“I wish that I had been more visible to others,” Forthaus said. “Many athletes suffer in silence and hide who they are because of stereotyping and discrimination in sports, so I wish I could’ve reached out to others who were also kind of hiding themselves in an attempt to be normal.”While Forthaus and Willmore are both members of the LGBTQ community, their experiences as athletes are far from the same. Willmore said he has had a great experience as an LGBTQ athlete, and his identity made him more well-known around the school. His family and friends have supported him, and he said the one time in his life a person threw a homophobic slur his way, his friends chased the guy down and beat him up.

“If anyone has a problem with you coming out, they keep their mouths shut because of the huge backlash they would get,” Willmore said. “It’s easy for me to say that because I personally haven’t received any negative experiences, but I truly believe that if you’re confident and own who you are people aren’t going to mess with you.”

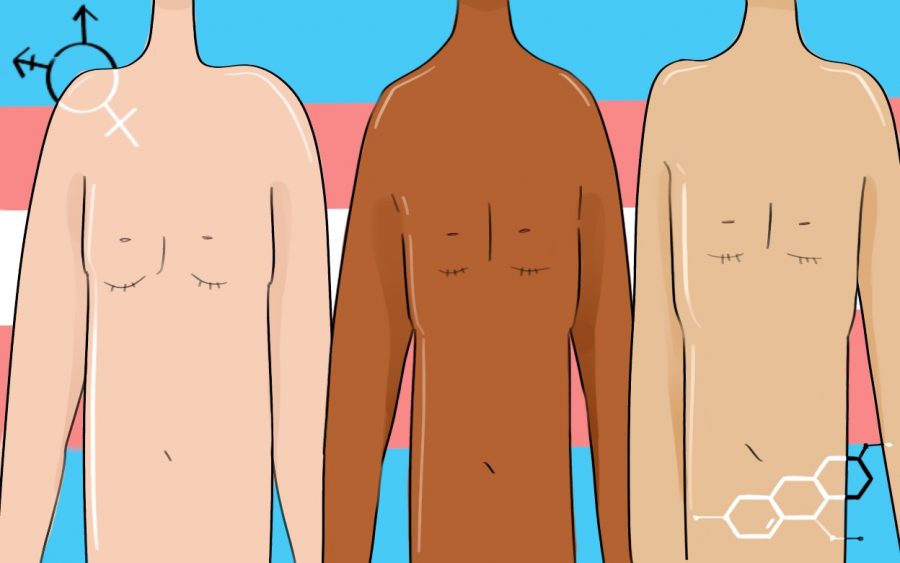

Through open communication, LGBTQ-inclusive codes of conduct and LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination policies, the National Collegiate Athletic Association is taking steps to provide schools with diversity and inclusion resources and protect LGBTQ athletes. Today’s youth is also in agreement that policies and protection for LGBTQ people need to strengthen, and 95% of youth want hate crimes to cover sexual orientation and gender, according to LGBT SportSafe. Dr. Brown said being one’s authentic self takes courage and sometimes comes at the price of standing alone, but with courage, confidence, allyship and the strength of one’s own voice, being an LGBTQ person will become more normalized. There is no one way to be an LGBTQ athlete, just as there is no one way to be a member of the LGBQ community.

“To athletes who are fearful of coming out: those who don’t accept you won’t accept you no matter what,” Forthaus said. “Your teammates will be inclusive if they’re inclusive, and your sexuality shouldn’t determine that. Fight for your rights and those who come after you.”

How do you support LGBTQ athletes in your community? Let us know in the comments below.[penci_authors_box_2 style_block_title=”style-title-11″ columns=”columns-2″ post_desc_length=”20″ number=”2″ order_by=”user_registered” include=”5, 75″ block_id=”penci_authors_box_2-1593280135379″]