The female gaze counteracts existing standards in cinema

December 20, 2021

In every visual representation in media consumed, the creator controls the perspective through which audiences view the work. The female and male gazes are two defined examples, primarily found and discussed concerning cinema, of said perspectives intentionally curated to guide how viewers are meant to engage with the content. The term “male gaze” has its roots in feminist film theory, with scholar and filmmaker Laura Mulvey first coining the term in her 1975 essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

Drawing from a psychoanalytic standpoint, Mulvey asserts films that engage with the male gaze aim to satisfy a concept Sigmund Freud popularized called scopophilia, which translates to “the love of looking.” As a result of pandering to cis, heterosexual masculine perspectives, women in cinema are often sexualized and objectified. As outlined by Mulvey’s essay, the camera acts as the eyes through which men see and display women for their “to-be-looked-at-ness.” Female characters serve only as a symbolic “bearer of meaning” for one of three potential “makers of meaning”— the filmmaker, the male character and the viewer.

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female,” Mulvey wrote. “The determining male gaze projects its [fantasy] onto the female form which is styled accordingly.”

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its [fantasy] onto the female form which is styled accordingly.

— Laura Mulvey

Movie examples of the male gaze are easy to find. From Marilyn Monroe’s roles playing the “Brainless Beauty” trope in works such as “Some Like it Hot” and “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” to animated characters like Jessica Rabbit, filmmakers project the gaze onto female characters with varying degrees of subtlety and awareness. Some films maintain the male gaze even with the inclusion of complex backstories and strong motivations for female characters. Female superheroes and villains in popular franchises like Marvel and DC still sport tight or revealing clothing that sticks out from their male colleagues, despite having essential roles contributing to the plot. From Catwoman’s latex bodysuit to Harley Quinn’s ripped shirt, fishnets and tiny shorts and Black Widow’s poses framed to show off her body, the characters were constructed — in some cases by completely moving away from their original designs, like Harley Quinn, who wore a full-length jester suit in earlier designs, — to be looked at by the audience.

On the more transparent side of the spectrum, blatant examples of characters derived from the male gaze include the James Bond movies and their eroticization of the “Bond girls,” who only exist as alluring distractions to the hero. James Chapman, author of “License to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films,” said Bond girls are in the movies “purely for decoration […] the girl is literally reduced to the level of an object.”

In the infamous scene in the 2007 Transformers movie where Megan Fox’s character leans over to fix a car, the positioning and close-up shots clearly emphasize her body as the focal point of her character. In these hypersexualized scenes, the characters are not behaving naturally, rather distorting real-life circumstances with the projection of male fantasy, which takes away from the character’s human-like-ness.

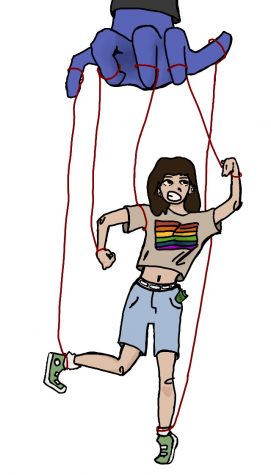

Movie representations of women depicted through the male gaze harm them by actively perpetuating patriarchal ideals, which seek to limit women in demeaning ways and define them with labels of unimportance and over-sexualization, in contrast to the elevated experience of the heterosexual man. These ideas permeate through societal views and manifest themselves in direct experiences like catcalling or unfair dress codes. Constant exposure to these views also affects women’s self-perception and self-esteem, causing women to monitor themselves and their bodies in the same ways they believe men are observing them. This process is called self-objectification and, when recognized, becomes an ever present extension of the patriarchy, which the women themselves inadvertently uphold.

In these hypersexualized scenes, the characters are not behaving naturally, rather distorting real-life circumstances with the projection of male fantasy, which takes away from the character’s human-like-ness.

Margaret Atwood, feminist poet, novelist and literary critic, highlights the implications and ramifications of self-objectification in her 1993 book “The Robber Bride.” “Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? Up on a pedestal or down on your knees, it’s all a male fantasy: that you’re strong enough to take what they dish out, or else too weak to do anything about it,” Atwood wrote. “Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you’re unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

The realization of appearance as a social currency creates a societal emphasis on how a woman conforms to the standards of the male gaze, and this pressure results in adverse psychological effects for women related to body image and confidence. A 2011 study by the American Psychological Association stated, “mere anticipation of a male gaze increased self-objectification in young women and led to greater body shame and social physique anxiety when compared to participants who anticipated a female gaze or no gaze at all.”

In direct contradiction to the male gaze, the female gaze represents a female perspective of a story. Because there is no pre-existing systemic power difference, as the patriarchy creates, the female gaze does not parallel the male gaze in its oppression of the opposite sex. Similarly, because characteristics of the female gaze center around emotional transparency and vulnerable intimacy, the objectification and hypersexualization of men do not exist under it. Instead, in movies like “Lady Bird” and television shows like “The Handmaid’s Tale,” the female gaze aids women in offsetting the negative repercussions of the male gaze, freeing them from their subjugation and even men from their roles of the aggressor, sexual pursuer or consumer of women.

Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? Up on a pedestal or down on your knees, it’s all a male fantasy: that you’re strong enough to take what they dish out, or else too weak to do anything about it. Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you’re unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.

— Margaret Atwood

The film industry is a heavily male dominated field, with a 2018 report from the BBC stating nine out of ten movies had more men than women in prominent cast and crew roles. Additionally, women made up only 12% of directors and 8% of cinematographers. It is therefore doubly important that women have space within the industry for more varied perspectives and create movies targeted toward more diverse audiences.

Not only does the female gaze succeed in exhibiting outlooks of an underrepresented demographic, it can also become a tool used to break down and counteract the male gaze. The redesign of Harley Quinn’s character in the female written and directed movie “Birds of Prey” examples the subversion of the male gaze through the female gaze with a new look, consisting of jean shorts and a loose-fitting t-shirt with her own name stamped across the front — compared to “Daddy’s Lil Monster” in “Suicide Squad” — giving the character a sense of ownership over her identity lacking in previous portrayals. “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” is another example of a female directed film which internalizes the female gaze. As an exploration of female sexuality, it almost entirely removes the influence of men from its narrative and reclaims the representation of queer women in a space where men have long fetishized their existence.

In this way, filmmakers can employ the female gaze to create representation for all women, including queer women and women of color who are especially marginalized by the effects of the male gaze. By helping them effectively recognize instances of the male gaze by contrast, and contributing to the deconstruction of long held societal views and expectations of women, the female gaze becomes a necessary implement for women to resist and fight against the restrictions of their long-held representation in cinema.

Have you seen films created in the female gaze? Let us know in the comments below.

Luke Stagg • Dec 20, 2021 at 6:38 pm

This is a great article!! A movie that comes to mind for me is Jennifer’s Body, directed by Karyn Kusama. The movie is all about sexuality but Kusama uses the male gaze as a weapon against the male characters with the love story and attraction between Amanda Seyfried and Megan Fox being deeper than skimpy outfits. Another example could be WandaVision, which isn’t by any means an exploration of the male gaze, but head writer Jac Schaffer kind of inherently works against it by putting Wanda in outfits culturally accurate to sitcoms through the decades until finally revealing her badass, non-sexualized superhero outfit. Again, this is a super thoughtful article that’s well-researched on an important lesson in art-making