The male and female physiologies are different down to the cellular level. Females have two X chromosomes but no Y chromosomes while men have one of each. Men have a 36% greater skeletal muscle mass than women. Testosterone is the main sex hormone for males while estrogen maintains females’ mentrual and reproductive systems. Physiological differences between genders such as these and others are essential for understanding and developing treatments for diseases and conditions.

For one, alcohol impairs females more strongly than males, according to Harvard Medical School. Female bodies contain proportionately less water and more fat than male bodies. Water dilutes alcohol and fat retains it, so female organs are exposed to higher concentrations of alcohol for longer periods of time. As a result, one drink for a woman is roughly equivalent to two drinks for a man.

Dr. Mahesh Thakkar, University of Missouri—Columbia School of Medicine’s Department of Neurology Director of Research, examines the role of alcohol addiction in sleep disorders in his experiments. His lab is focused on understanding the pathophysiology of sleep disorders in humans and animal subjects.

“Stress-induced sleep changes in females are more robust as compared to males, and that is dependent on [the] estrous cycle,” Dr. Thakkar said.

The estrous cycle, the period in the sexual cycle of female mammals (excluding higher primates such as humans, who have menstrual cycles instead), is just one of many differences between the male and female bodies. The varying estrogen and other circulating hormones mean Dr. Thakkar must monitor the estrous cycle of his subjects while experimenting. Because the subjects all have cycles that occur at differing times, this helps to make sure the controls and treatments are performed on the same estrous day. Not all labs, however, take the same steps as Thakkar.

“One of the most prominently believed rationales for male bias in research is that the estrous cycle significantly complicates the study of physiology in females,” a 2016 article by the Medical College of Wisconsin stated. Because of this, the varying hormone levels could make experimentation in female organisms more difficult, leading labs to only research males.

Although experimenting with female subjects involves the extra step of monitoring the estrous cycle, choosing to only research male subjects contributes to what the article calls “overwhelming male bias in pre-clinical scientific research.” For example, the ratio of male to female animal subjects in pharmacological research was almost 6:1 in 2016, which limits the potential of scientific discovery for women more than men, according to the article. Without equal representation of both sexes while conducting research, there cannot be equal opportunity for healthcare advancement.

Senior Meredith Farmer, who wants to work in a medical microbiology lab in the future, said she believes gender bias in research must be addressed. She said she wants to work with vaccinations and medications that have global and practical effects on human lives. “Studying both genders is incredibly important because, in the past, only the male health problems have been addressed.”

“When the birth control pill [was first available], it had negative effects on women due to the extremely high doses of hormones,” Farmer said. “The pill was advertised, but … the long term effects were unknown.”

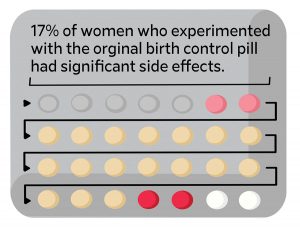

When birth control pills reached the market in 1960, the original brand, Enovid, had much higher levels of specific hormones than necessary to prevent pregnancy. According to Planned Parenthood, a nonprofit organization which provides reproductive healthcare, it contained 10,000 micrograms of progestin and 150 micrograms of estrogen in contrast to today’s 50–150 micrograms of progestin and 20–50 micrograms of estrogen—a vast difference from today’s safer, equally effective levels.

It took scientists more than a decade to recognize the risks of the high hormone levels. One woman died of congestive heart failure, and another developed pulmonary tuberculosis after a trial. Gregory Pincus, one of the researchers who pioneered the pill, ignored the problems and the gravity they held. “These side-effects are largely psychogenic. Most of them happen because women expect them,” Pincus told the New York Times years after the trials, according to Harvard University’s newspaper publication, The Harvard Crimson.

“I think that if it were a men’s product, testing would’ve been done to ensure that it was safe, but because of the gender bias, the same standards didn’t apply for women,” Farmer said. “The gender bias is much better than it used to be but it still continues into today.”

Even with diseases such as AIDS that affect one sex more than the other, researchers must still study both sexes in order to maintain safe treatment. Dr. Michelle Teti, an associate professor in the Department of Health Sciences in the School of Health Professions at the University of Missouri — Columbia, conducts HIV and sexual health research. Approximately 23% of people living with HIV in the U.S. are women, according to amfAR, a nonprofit AIDS research organization.

“Just because women make up a smaller proportion of cases of HIV does not mean they are not important to understand,” Dr. Teti said. “As a public health researcher, I also look at trends in illnesses. It’s important, for example, that the cases of HIV among women have grown over time, and that certain groups of women, like young women, increasingly become infected with HIV.”

For much of the American scientific landscape, researchers considered the male body to be the “norm” study population. In conditions such as coronary heart disease, which is the leading cause of death for both genders, according to Harvard Medical School, research funding is far greater for men than women. The lack of funding means less scientific advancement, and therefore, less healthcare advancement for women.

“When we only understand the experiences of one gender and an illness (like men), we fail to understand what people who identify as women need when they are sick, and even how they get sick,” Dr. Teti said. “We wind up knowing less about medicine and dosages, but also about people’s psychological and social needs.”

How do you think biased research affects the future of women’s health? Let us know in the comments below.