Throughout my entire adolescent life, I’ve felt left out. Especially during elementary and middle school, it seemed like I never fit in with social groups. From my olive-colored skin to my thick, curly hair, I envied my friends’ physical features; I always wished I had blue eyes or blonde hair.

I felt a perpetual sense of “otherness,” as if every person I passed somehow knew I was hiding a part of myself. I felt ashamed of how my parents and I looked, but I struggled to place the source of my discomfort.

When I was younger, I attributed my differences in skin and hair to the color of my mother’s brown tone. I felt like I had two white parents: a white father, and a slightly darker, but still white, mom.

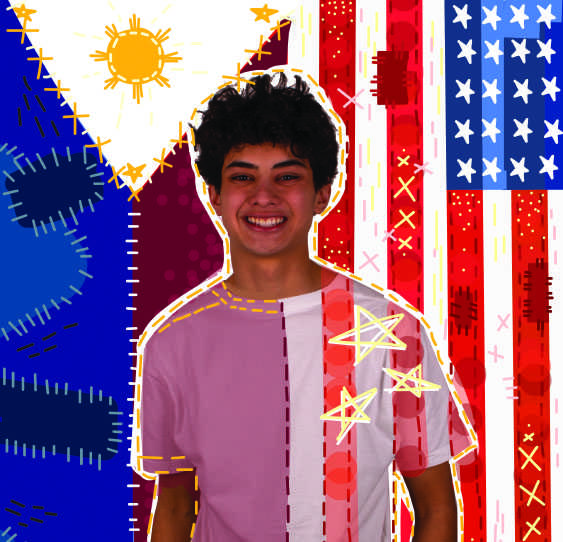

Race was a difficult concept to grasp. My white-passing privilege granted me the luxury of not experiencing overt racism, but I couldn’t understand the social implication of being a biracial American. In a school that was empirically white, it was easy for me to fit in with the rest of the white crowd and completely neglect my Filipino side.

Filipino and white culture are polarized, and it makes being somewhere in between confusing. Wasian culture, characterized by being a half-Asian, half-white teenager, is prominent on social media platforms like TikTok; although there is a Wasian community online, Columbia is not known for its diversity.

As a Wasian, I lack a sense of cultural identity. While white and Asian people find assurance in their race since they are able to socialize with other whites or Asians easily, forming groups of only their respective race, I face the opposite. There’s no club for us like the South Asian Student Union or Wasian appreciation month, making it difficult to meet others like me. I felt left out of both cultures. I’m too Asian for the white crowd but too white for the Asian crowd.

I also couldn’t relate to either side of my family, which was especially hard at family gatherings. I can recall countless times when I walked into a Filipino relative’s house and my tiyas and titos showered me with compliments, which usually preceded a line of people waiting to get into the kitchen, eager to eat food. Shortly after a meal, we would all sing karaoke and eat halo halo while my relatives played cards a few feet away.

On my father’s side, however, I learned all the colloquial manners a young white man should learn: no elbows on the table, only speak when I was spoken to, ask to be excused from the dinner table. My cousins and I would sit at the kids’ table, away from the grown-ups. Even after dinner, while families were socializing amongst themselves, I tended to stick with my brother and sister, separate from the rest of the group.

The customs from each respective culture clashed with each other, leaving me unsure as to how I should act at events. For example, at a recent family reunion to a lakehouse on my father’s side, my relatives were confused when I didn’t put on sunscreen, neglecting to acknowledge the fact that I don’t sunburn. I didn’t know whether I should put on sunscreen to fit in, or if I should explain that my Filipino genes protected me from harmful sun rays.

Outside of family events, I still felt out of place. Throughout elementary school, I had a variety of social problems. As a shy kindergartener, it was a strain to make any friends because there weren’t any Wasians in my grade; it would’ve been great to know other Wasian kids to play with at recess.

Even at assemblies or gatherings, I felt uncomfortable because my mother was there. My friends’ moms toted large handbags and formed cliques with other white mothers.

But my ina is brown.

When I saw her sitting alone at assemblies, I tried to disassociate with her. I would stay with my friends, avoid hugging her and refuse to hold her hand. I tried to act independent. My mom’s thick, curly, black hair, a trait I shared, varied greatly from other moms. My mother called me anak rather than son. Instead of bedtime stories, she read verses out of her Bible until I fell asleep.

She didn’t like to attend baseball or football games, but she loved Manny Pacquio’s boxing matches. She would smile and wave at my friends, and when they asked who the brown lady was, I embarrassingly told them she was my mother before quickly starting another conversation, only furthering my sensitivity on the subject of my race.

In middle school, when teachers or classmates questioned my race, I wouldn’t respond with “Filipino” or “biracial.” I said “white.” If someone asked why I looked a little dark, it would only be then when I told them I was half-Asian.

What began as questions from others evolved into a problem of introspection. I didn’t know if I should “act like” or try to be white or Asian. When a snotty person said, “No way” or “You don’t even look Asian,” I wondered if I should apologize for my facial features or feel offended by the rude remark. I blamed myself for being different.

I was satisfied living with the dilemma of not knowing my own race, but about halfway through my junior year, I ironically downloaded TikTok to further satisfy my perpetual procrastination. My preconceived TikTok assumptions consisted of kids doing bad dances to radio pop music, but I was shocked to see there was an entire community of others like me on the app. For weeks after I first got TikTok, I remember scrolling through the “For You Page,” a personally catered page of viral videos, watching biracial Asian-American teenagers show off rice cookers and Asian food while Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline” played in the background.

Along with boosting multiracial appreciation, this surge of Wasian culture introduced virtually an entire generation of TikTok users to the realities of the identity crisis I faced as a child. It was weird watching half-white, half-Asian kids portrayed so frequently and positively on social media. For the first time, I was proud to be Wasian. I felt a sense of community, like entering a warm home, even if it was with a few kids who went viral on social media. After seeing how many other people like me exist, I finally realized I don’t have to “act” white or Asian to fit in. I can express myself authentically, and find solace in being different, hoping others do the same.

Although I am grateful to have found a community through niche apps like TikTok, other multiracial people have difficulties accepting their identity, too. There aren’t enough people for me to create a group to relate with, making it difficult for biracial or multiracial people to find a community. They are stuck in an awkward state of not being “enough” for either group.

I’ve lived my life without knowing a sense of community in my own race, but in hindsight, I’m beginning to understand how great it is to be diverse. After years of ignoring my own ethnicity, it’s extremely surprising, while at the same time perfectly apt, that a sound, informally labeled “Wasian check,” on TikTok helped me take the first step on my journey of self-appreciation and acceptance.

I’m proud to tell the world I’m biracial because it tears down the awkward race conversations I dreaded to have in the past. Hopefully, people see me for more than a Wasian kid — there is much more to me than my hair or eyes or skin color — and take the time to get to know me. I realize people are much more complex than just their race, and narrowing down my entire personality to a snap judgement or stereotype about the color of my skin is degrading to the rest of my personality.

Those of multiracial backgrounds have diverse and unique stories to tell. It’s fascinating to meet others who are more than a single race — to learn how their parents met, to converse about if they experienced the same problems I did as a kid. Only by hearing others’ stories did I accept my own.

I regret disenfranchising my ethnicity. The color of my skin is not a defining personality trait. Being biracial should not be the quality someone notices me for. I shouldn’t base my friend group, the clothes I wear or my likes and dislikes on my race. It’s gratifying to know there are people who have felt like me — left out by friend groups and out of touch with their own sense of self and belonging — who may now share the sense of community I currently feel.

Looking forward, I will look at people through a more accepting lens. There is so much more to people than the color of their skin or facial features, and it’s unfair to base a first impression solely on those factors.

Have you ever seen the “Wasian check” trend on Tiktok? Let us know in the comments below.

Sunny • Jun 12, 2021 at 10:16 pm

Wow I relate to so much in this article. I’m a quarter Filipino though so I feel like even more im not allowed to claim it as part of my identity/heritage because of the priveledge I have in being mostly white, and yet when I try to not claim it as part of me I find myself like. trying to hide it on purpose as to not seem like I’m faking something? It’s a weird delima.

londynn • Feb 10, 2021 at 12:55 am

hi! fellow half filipina, half white high school student here and found this article as i am reflecting upon my mixed race and specifically my wasian identity. especially as someone who is white passing, i guess i never have felt like my phenotype has attested to my strong ties to my filipino heritage (especially because my mom’s family embraces and continues those traditions). i especially relate to the not fitting type thing, yet maybe it’s okay to not always feel like you “fit”. idk. either way, this brought me a much needed sense of comfort that i’m not alone in these sentiments. so thank you.

Lee • Oct 4, 2020 at 9:15 pm

im also half pinoy and half white, and knowing that someone out there feels the same i do is, quite honestly, reassuring. i’ve often found myself wishing i was only one race, because i wouldn’t have to deal with my lost sense of self. i’ve done some digging, and it’s called racial impostor syndome. you feel like you’re not actually part of the culture you are, and it can really hurt you. i’ve seen the tiktok “wasian check”, but honestly, my pinoy family is so westernized that seeing everyone whose family strongly embraces their traditional culture made me kinda envious, which is ridiculous. speaking of traditional culture, i want to wear filipino traditional clothing, but i’m worried i’ll be made fun of or not accepted because i’m a “half-blood”, and yes, i’ve been called that. thing is, nobody else in my pinoy family is biracial. i often feel like the odd one out. my brother is too young to understand this, so i feel really alone. so i guess what i’m trying to say is thank you for writing this, it made me feel less alone

britton • Feb 3, 2021 at 10:46 am

This is exactly how I feel. Sometimes because I live in a predominately white city and rarely get to see my Filipino side of the family, I don’t feel like I’m ‘truly’ Asian enough or something; like I’m just a white person appropriating the culture because (as one of my friends in elementary once said to me) technically I “was raised just like any other white person, so I’m basically just white”. Stuff like that makes me feel guilty to even have an interest in wearing traditional Filipino/Chinese clothing, and I feel like I’m not as connected with the culture as I should be. But thank you for this, it really speaks to me and I’m really glad I found it.