[heading]Athletes put enough time, effort into sports to earn physical education credits[/heading]

Ever since I could walk, sports have been a vital part of my life. Whether it was ballet at age three, swimming at five, softball at nine or cross country at 10, I was continuously enrolled into some form of a sport.

In elementary and middle school, physical education classes were the highlight of my day. I looked forward to the class where I could run around and compete in a game of dodgeball or capture the flag. However, as high school came next, and classes started to count for credits, I was annoyed to see that P.E. was a required class for graduation. If I already participated in a sport, I saw no benefits in the recreational games that were performed in the 90-minute class.

In middle school, sports were nothing more than a couple practices a week with games consisting of no one in the stands except for parents of the athletes. But in high school, it’s serious business. With 6:15 a.m. practices and games weekly, the atmosphere of high school sports is sure to leave sore muscles that can not be compared to the middle school world of athletics.

Why would jogging around the gym, mixed in with some stretches and a game, count as credit while mile repeats at the crack of dawn don’t count for anything? Conditioning or speed workouts on the track are far more intensive yet are not acknowledged for the time and effort put into them.

The 90 minutes filled with games of ultimate Frisbee do nothing to build up stamina or strength. Never in my years in a physical education class have I found myself drenched in sweat, breathing in gulps of air the way practices drain me.

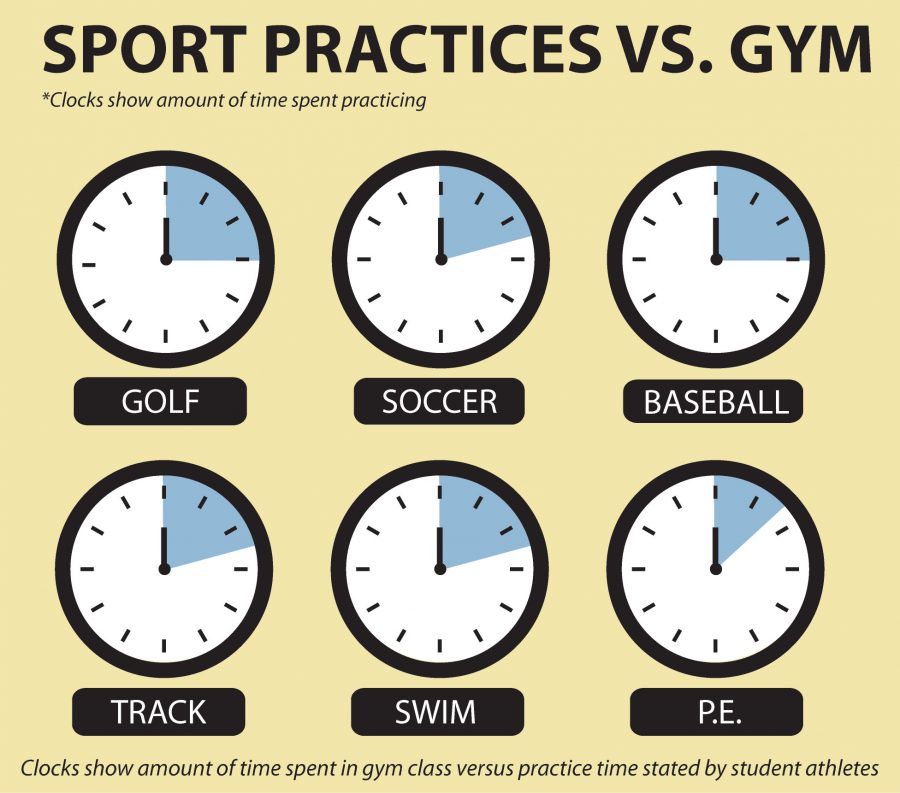

The National Association of Sports and Physical Education recommends that school children participate in 150 minutes a week of physical education. For student athletes, most practices are least an hour long, usually longer. Many students spend five days a week working out from after school practices alone. These athletes would be completing 300 minutes, double the recommended amount. On top of practices, tournaments, meets, and games fill the weekends for student athletes. The extra minutes in gym classes could result in overuse of muscles and increase the chance of injuries.

In a five-day school week, most students get two to three classes of P.E. per week depending on the schedule and day. This calls for around three to four and a half hours of physical activity per week. After a semester of these classes, students are able to gain a half credit of P.E. For extracurricular sports, practices are usually held every day, lasting as long as three hours. Already in a week, student athletes could be taking on 15 hours of practices — around five times more than required classes in school. Still, that student athlete receives no credit.

While physical education classes are not training you to be star athletes, do the P.E. courses add anything to students who are already participating in an extracurricular sport?

Physical education classes are meant to promote healthy lifestyles and ensure good health of students so they can meet the recommended minutes of physical activity per day. To student athletes, the mile walk probably feels like a breeze and the core workout just a fraction of what is done in sports practices. If P.E. classes are supposed to help get heart rates up, these slow paced, tedious sessions of so-called physical education don’t actually benefit our health.

If a sport could count as a physical education credit, it would free up one block for athletes, allowing for new class options. It would open up opportunities for student athletes to branch into fields of study that can only be experienced during one’s high school career. Whatever the option, being able to add a new class that could count as a credit toward what would help in the future would be more useful than the speed-walking around the gym or the recreational game of flag football.

When next year rolls around and you are forced upon another class schedule form sheet, choose the classes first, not the unwanted P.E. course. Save that for later or take it as a summer school class. Instead, replace the unnecessary course with a more desired and applicable course, which could help one to not only veer towards a specific career goal but also enable all students to enjoy a variety of classes.

A current goal for the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is to become a top 10 state for education by 2020. Becoming a high ranked school across the nation calls for a range of approaches to gain credit — something our state currently lacks. With the potential to gain P.E. credits through sports, students would be able to higher their level of education by selecting new courses that have been high on their list.

In elementary and middle school, physical education classes were the highlight of my day. I looked forward to the class where I could run around and compete in a game of dodgeball or capture the flag. However, as high school came next, and classes started to count for credits, I was annoyed to see that P.E. was a required class for graduation. If I already participated in a sport, I saw no benefits in the recreational games that were performed in the 90-minute class.

In middle school, sports were nothing more than a couple practices a week with games consisting of no one in the stands except for parents of the athletes. But in high school, it’s serious business. With 6:15 a.m. practices and games weekly, the atmosphere of high school sports is sure to leave sore muscles that can not be compared to the middle school world of athletics.

Why would jogging around the gym, mixed in with some stretches and a game, count as credit while mile repeats at the crack of dawn don’t count for anything? Conditioning or speed workouts on the track are far more intensive yet are not acknowledged for the time and effort put into them.

The 90 minutes filled with games of ultimate Frisbee do nothing to build up stamina or strength. Never in my years in a physical education class have I found myself drenched in sweat, breathing in gulps of air the way practices drain me.

The National Association of Sports and Physical Education recommends that school children participate in 150 minutes a week of physical education. For student athletes, most practices are least an hour long, usually longer. Many students spend five days a week working out from after school practices alone. These athletes would be completing 300 minutes, double the recommended amount. On top of practices, tournaments, meets, and games fill the weekends for student athletes. The extra minutes in gym classes could result in overuse of muscles and increase the chance of injuries.

In a five-day school week, most students get two to three classes of P.E. per week depending on the schedule and day. This calls for around three to four and a half hours of physical activity per week. After a semester of these classes, students are able to gain a half credit of P.E. For extracurricular sports, practices are usually held every day, lasting as long as three hours. Already in a week, student athletes could be taking on 15 hours of practices — around five times more than required classes in school. Still, that student athlete receives no credit.

While physical education classes are not training you to be star athletes, do the P.E. courses add anything to students who are already participating in an extracurricular sport?

Physical education classes are meant to promote healthy lifestyles and ensure good health of students so they can meet the recommended minutes of physical activity per day. To student athletes, the mile walk probably feels like a breeze and the core workout just a fraction of what is done in sports practices. If P.E. classes are supposed to help get heart rates up, these slow paced, tedious sessions of so-called physical education don’t actually benefit our health.

If a sport could count as a physical education credit, it would free up one block for athletes, allowing for new class options. It would open up opportunities for student athletes to branch into fields of study that can only be experienced during one’s high school career. Whatever the option, being able to add a new class that could count as a credit toward what would help in the future would be more useful than the speed-walking around the gym or the recreational game of flag football.

When next year rolls around and you are forced upon another class schedule form sheet, choose the classes first, not the unwanted P.E. course. Save that for later or take it as a summer school class. Instead, replace the unnecessary course with a more desired and applicable course, which could help one to not only veer towards a specific career goal but also enable all students to enjoy a variety of classes.

A current goal for the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is to become a top 10 state for education by 2020. Becoming a high ranked school across the nation calls for a range of approaches to gain credit — something our state currently lacks. With the potential to gain P.E. credits through sports, students would be able to higher their level of education by selecting new courses that have been high on their list.