Widely regarded as some of the most graphic and brutally violent moments in cinematic history, the first 27 minutes of Steven Spielberg’s academy-award winning war epic “Saving Private Ryan” depict war in all its raw savagery.

The chaotic, horrifyingly realistic reenactment of the Omaha Beach landing features bright red gore and severed arms flying through the air as American soldiers storm the German occupied coast. Watching even the first few opening moments of the film is an experience many reviewers on sites like Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes describe being as memorable as is terrifying.

During the past few decades, groups like the American Academy of Childhood and Adolescent Psychiatry and Common Sense Media have argued that the growing presence of gratuitous violence in American media, like the sort found in “Saving Private Ryan,” has had a profoundly negative impact on younger generations’ psyche as well as adults. Such organizations often make the claim that violent media, especially the R-rated variety, desensitizes Americans of all ages and increases aggression across the country.

Not everyone agrees on the matter, however. Amateur filmmaker and senior Ian Gibbs said accurate portrayals of violence can have a significant and positive impact on society. The founder of RBHS’s Society for Cinematic Greatness club and president of the school’s True/False Film Club, Gibbs argues that violence plays an important role in media. He said the more realistic a film’s portrayal of blood and gore, the better it firmly reinforces for its audience that real world violence is truly awful and terrifying.

“When we see James Bond dispatching several opponents without seeing the impact of his punches, we tend to believe that’s how it works in real life,” Gibbs said. “However, if we see the blood and the pain in the eyes of the opponent, then we think to ourselves ‘Wow, I hope I never have to do that.’”

Jim Klagge, a professor of philosophy at Virginia Tech, agrees with Gibbs’ feelings that violent media can have a positive impact upon society. Klagge said that portrayals of violence can act much like the philosopher Aristotle’s notion of “catharsis,” the belief that tragedies can purge the body of negative emotion. Violent media, he says, can help the viewer to work through their emotions.

“My main thought is that violent media allows people to blow off steam without actually hurting anyone,” Klagge said. “I like the line from [American rock musician] Chris Cornell: ‘It gives you a chance to release those dangerous impulses without hurting yourself or anyone else.’”

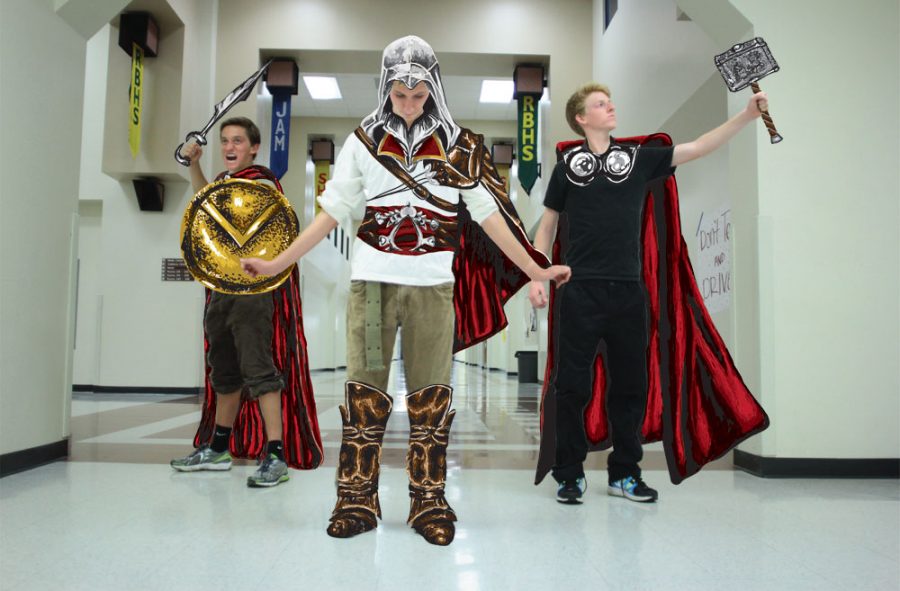

Alongside television and cinema, violent video games, such as Assassin’s Creed, Call of Duty and the upcoming Dishonored, stand accused of desensitizing Americans to real-life violence. A 2011 international joint-effort study by psychology and communications experts from the University of Missouri-Columbia, Ohio State and Vrije University supports such a claim.

Data collected from subjects exposed to violent images and games helped support the claim that media violence can desensitize its audience. The experiments conducted during the study showed that people exposed to higher levels of violence in games and other media had reduced brain response to depictions of real-life violence.

However, recent research conducted by New York University suggests such games can have positive effects on the player. When used as part of a balanced entertainment diet, they can stimulate thought, increase synapses, improve concentration and aid in stress relief.

Both Klagge and Gibbs said it’s important to limit the access younger children have to graphic media, particularly those with ‘mature’ ratings. One issue with using such ratings as a barometer, however, lies in the fact that many of the organizations that rate American media, such as the Entertainment Software Rating Board and Motion Picture Association of America, often judge different works based on an inflexible set of guidelines rather than evaluating films on an individual basis.

Critics of the system being used at present say the approach doesn’t take violence seriously enough and gives access to wide audiences instead of the people for whom such media is appropriate and potentially positive. Some argue the rating boards are inclined to determine ratings based too heavily on sexual content and profane language and not enough on violence.

“I’m not a big fan of the rating system, as it tends to label sex as much worse than violence, even though sex is a more natural part of life and it shouldn’t be demonized,” Gibbs said. “Go ahead and show the movie where people are being murdered left and right but, God forbid, we show someone having sex.”

Across the country, people continue to fervently debate whether or not violent media causes violence. Dozens of research programs conducted over the past decade show limited results, most of which are fairly inconclusive at best. Debates rage over the risk of creating violent media as a result of claims that such media has caused an upturn in violent crime and school shootings.

Klagge was on sabbatical during the tragic 2007 shooting at Virginia Tech; he found out about the massacre Monday morning on the news and returned to the school in time for the aftermath. The shooting produced a cascade of heated discussion as to whether or not the shooter, Seung-Hui Cho, committed the atrocity as a result of the impact of violent television and cinema. Klagge feels that such questions don’t encapsulate the issue.

“The question arises whether violent media provoked or encouraged Cho to do that. It’s possible. We’ll never know for sure,” Klagge said. “My thought is that even if violent media can have a serious downside, we can’t ignore the upside too.”

By Jake Alden