Life, though, is not efficient. It is not always purposeful. And it certainly is not spared extra details and seemingly pointless character quirks.

T/F documentaries are extremely rewarding in this respect because of how beautifully full each character is. They are all real people, so unlike in other movies, they have all the characteristics, relationships and personal histories that each of us carry around. In a movie, a character may fall in love with the wrong person just to provide contrast for when they fall in love with the right one. In a documentary, a character may fall in love with several ‘wrong’ people or several ‘right’ ones just because they fall in love.

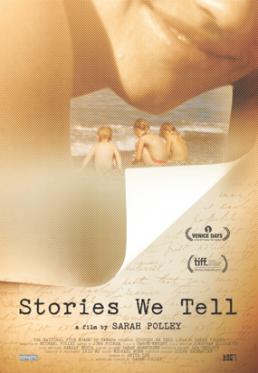

Sarah Polley’s “Stories We Tell” is a film acutely aware of its ‘documentary’ status.

‘How’s this angle?’ Polley’s interviewees ask. ‘How do my breasts look?’ her brother jokes.

The subjects’ comments about the fact that they’re being interviewed are reminiscent of, and often as funny as, the feel of the show The Office. But unlike The Office, unlike most movies, actually, the person behind the camera is the main character. She’s also the director.

The documentary is about Sarah Polley’s family, focusing on life after her mother’s death. Though Polley lost her mom years before the start of the project, it is obvious that her absence is still fresh. Mostly, the movie is the production of the most intimate thoughts of a family’s story brought forward candidly; each character’s honesty is remarkable, but the compilation of such openness is overpowering, as if you have suddenly been let in on all the family’s secrets. It feels inappropriate, as if you are eavesdropping, so it also subsequently fills you with awe at how much access you are given.

The film’s first 30 minutes feature an influx of character introductions, each with just a name, rather than a job title or family relationship or background summary. As the various interviewees’ responses start to interact with one another, the various bonds between the characters start to become more evident. This unraveling of characters is more eloquently beautiful than any forceful character development would have been, representative of the film overall.

Beyond the premise of the film and the honesty of the characters, the storytelling itself is superb, and the plot flows fluidly. It’s thought provoking, as the best documentaries are, and you leave chuckling about the various contradictory answers to the same question, debating about which ‘truths’ were maybe a little bit truer, and, most of all, wondering about, well, the stories we tell.

By Nomin-Erdene Jagdagdorj