Taw holds a larger responsibility in his home than most teens at RBHS; his parents are highly dependent on him and his siblings because they cannot speak English. Taw, being the oldest of six, said he doesn’t mind this burden in the least because he is so relieved to live in America.

“I am not tired about [helping my parents.] I am happy about this,” Taw said. “In Burma, life was harder. It was not about things. But here, I can work and help my family.”

An English Language Learner student here, Taw is not alone. About 20.3 percent of American families spoke a language other than English in their homes between 2007 and 2011, according to the U.S. census. For some, it is their only language, and their children are their translators.

Taw and his family came to America about four years ago, but from the age of 12, Taw lived in a refugee camp on the border of Burma and Thailand.

“The Burmese army came to our village and destroyed the village and burned all the house,” Taw said. “We didn’t have home. We didn’t have a country. We didn’t have freedom. If we go to Burma, they would kill us; if we go to Thailand, they put us in jail. So we cannot go anywhere.”

But, in 2008, Taw and his family applied to come to the United States, and in October of the next year, the United Nations heard his family’s plea and allowed them to come to Columbia, Mo. Taw said the trip was the longest journey of his life, and at its completion, he discovered a completely different world than he had known existed. He used an indoor toilet for the first time and tried to make sense of the chaotic airports he was sleeping in. His first flight was scary, he said.

“When I first went to the airplane, I thought I was going inside a cave. Huge, and I had never been,” Taw said. “The size, noise and you move a little bit. Your body shakes.”

The trip, and all work after it, was worth the culture shock, he said, because once he arrived in the States, he had a safe home.

His father works at a “pork factory” and his mother takes care of the younger children. Taw said he believes he will have to help his father with English for the rest of his life because his father works everyday and “doesn’t have time to learn” the language. His mother, though, is learning slowly with a volunteer tutor who comes to their house once a week to help her learn the basics.

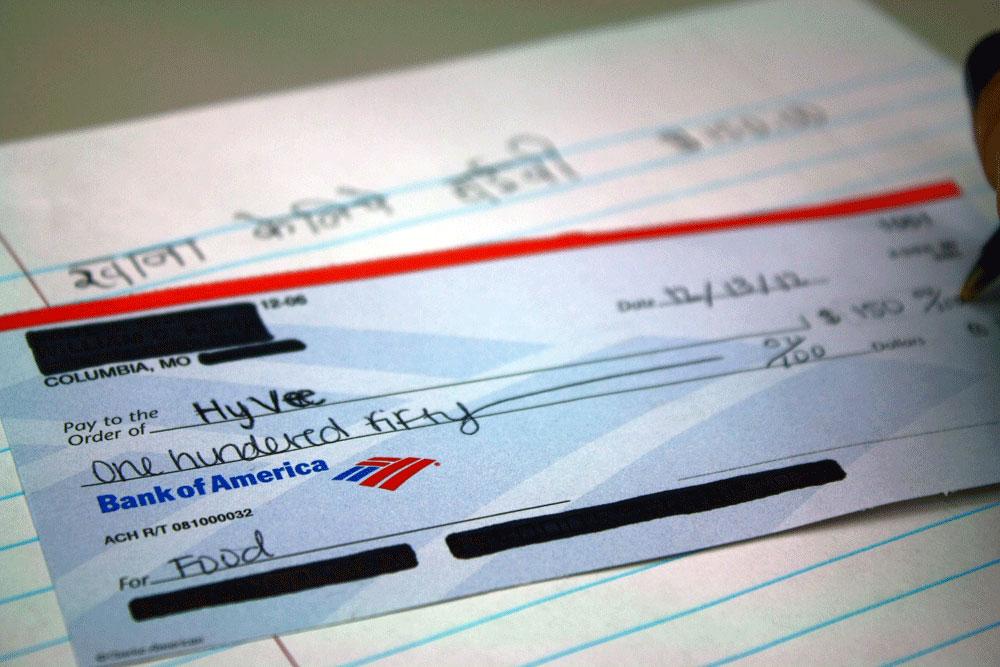

Still, Taw must help his mother in everyday situations. She cannot go to the supermarket without him because if she needs to ask the price or location of an item or there is a problem with the payment, he must be there to translate for her. Taw said his family is happy to have him around to translate for them, because they dislike wasting people’s time. This overwhelming self consciousness is a difficult, but common, problem for new speakers, said Lila Ben Ayed, one of RBHS’ two ELL teachers.

“For the beginning months or even years, non-native speakers struggle to feel confident enough to make mistakes and understand that most people don’t mind if someone has an accent or makes mistakes when they speak,” Ben Ayed said. “It’s not easy to feel stupid in front of other people. And speaking a language that is not your own, especially for older people, can be so hard.”

Sophomore Sohae Park had to make a similar leap when she first moved from South Korea. Although she knew basic words like “hello” and “thanks,” her language skills were pretty minimal. She said even today, she struggles to understand humor, sarcasm and American references that she has not heard of.

Still, she said she generally functions well in American society, even taking difficult English classes at RBHS. Although her English has vastly improved in the past few years, her mother has made little progress. Her age and her schedule make it difficult for her to pick up the language. Park said it was more than just a daily nuisance in helping her family with day-to-day translations; the language skill has become an emotional cyclone — messing up relationships in her family and creating difficult personal choices for her.

“When my mom was in Korea she had a big job. … She was a chief of a company. And she always was so busy, running around, never sleeping. She was so independent and powerful. I looked up to her and respected her so much. … But when we came to America, she was so dependent. She needed my help all the time, and my English was better than hers,” Park said. “It was so difficult for me … I felt like I respected her less … but I felt so bad about this. It is so hard.”

Park said this dependence changed their roles as child and parent. While in her home country, Park’s mother was the one who always knew best, but now Park finds herself put in a new position where her mother comes to her for advice and help. This responsibility, Park said, made it difficult to see her mother as a parental figure, rather than someone who was equal to her.

“My mother didn’t like this,” Park said. “It caused so many fights.”

ELL students can be in a position of doing more for their family than many English speakers, Ben Ayed said. Their parents will expect them to take younger siblings to school, help pay for the rent and translate various documents or signs.

“ELL students often have a lot more going on at home,” Ben Ayed said. “This is a lot of pressure sometimes, but they usually handle it really well. They love their families and want to help them, just like other kids.”

Taw said his family encourages him to continue his English studies, but it is difficult. And although he helps his family with many things, on days when he is worn out from the effort of learning a new language and living in a new world, his family returns the favor by making him smile and giving him advice.

“My parents always give me my happy. If I have a hard time, they make me feels happy,” Taw said. “They say, ‘It’s OK my son; you are a man. Never give up in your life and someday you will grow up and know more.’”

An English Language Learner student here, Taw is not alone. About 20.3 percent of American families spoke a language other than English in their homes between 2007 and 2011, according to the U.S. census. For some, it is their only language, and their children are their translators.

Taw and his family came to America about four years ago, but from the age of 12, Taw lived in a refugee camp on the border of Burma and Thailand.

“The Burmese army came to our village and destroyed the village and burned all the house,” Taw said. “We didn’t have home. We didn’t have a country. We didn’t have freedom. If we go to Burma, they would kill us; if we go to Thailand, they put us in jail. So we cannot go anywhere.”

But, in 2008, Taw and his family applied to come to the United States, and in October of the next year, the United Nations heard his family’s plea and allowed them to come to Columbia, Mo. Taw said the trip was the longest journey of his life, and at its completion, he discovered a completely different world than he had known existed. He used an indoor toilet for the first time and tried to make sense of the chaotic airports he was sleeping in. His first flight was scary, he said.

“When I first went to the airplane, I thought I was going inside a cave. Huge, and I had never been,” Taw said. “The size, noise and you move a little bit. Your body shakes.”

The trip, and all work after it, was worth the culture shock, he said, because once he arrived in the States, he had a safe home.

His father works at a “pork factory” and his mother takes care of the younger children. Taw said he believes he will have to help his father with English for the rest of his life because his father works everyday and “doesn’t have time to learn” the language. His mother, though, is learning slowly with a volunteer tutor who comes to their house once a week to help her learn the basics.

Still, Taw must help his mother in everyday situations. She cannot go to the supermarket without him because if she needs to ask the price or location of an item or there is a problem with the payment, he must be there to translate for her. Taw said his family is happy to have him around to translate for them, because they dislike wasting people’s time. This overwhelming self consciousness is a difficult, but common, problem for new speakers, said Lila Ben Ayed, one of RBHS’ two ELL teachers.

“For the beginning months or even years, non-native speakers struggle to feel confident enough to make mistakes and understand that most people don’t mind if someone has an accent or makes mistakes when they speak,” Ben Ayed said. “It’s not easy to feel stupid in front of other people. And speaking a language that is not your own, especially for older people, can be so hard.”

Sophomore Sohae Park had to make a similar leap when she first moved from South Korea. Although she knew basic words like “hello” and “thanks,” her language skills were pretty minimal. She said even today, she struggles to understand humor, sarcasm and American references that she has not heard of.

Still, she said she generally functions well in American society, even taking difficult English classes at RBHS. Although her English has vastly improved in the past few years, her mother has made little progress. Her age and her schedule make it difficult for her to pick up the language. Park said it was more than just a daily nuisance in helping her family with day-to-day translations; the language skill has become an emotional cyclone — messing up relationships in her family and creating difficult personal choices for her.

“When my mom was in Korea she had a big job. … She was a chief of a company. And she always was so busy, running around, never sleeping. She was so independent and powerful. I looked up to her and respected her so much. … But when we came to America, she was so dependent. She needed my help all the time, and my English was better than hers,” Park said. “It was so difficult for me … I felt like I respected her less … but I felt so bad about this. It is so hard.”

Park said this dependence changed their roles as child and parent. While in her home country, Park’s mother was the one who always knew best, but now Park finds herself put in a new position where her mother comes to her for advice and help. This responsibility, Park said, made it difficult to see her mother as a parental figure, rather than someone who was equal to her.

“My mother didn’t like this,” Park said. “It caused so many fights.”

ELL students can be in a position of doing more for their family than many English speakers, Ben Ayed said. Their parents will expect them to take younger siblings to school, help pay for the rent and translate various documents or signs.

“ELL students often have a lot more going on at home,” Ben Ayed said. “This is a lot of pressure sometimes, but they usually handle it really well. They love their families and want to help them, just like other kids.”

Taw said his family encourages him to continue his English studies, but it is difficult. And although he helps his family with many things, on days when he is worn out from the effort of learning a new language and living in a new world, his family returns the favor by making him smile and giving him advice.

“My parents always give me my happy. If I have a hard time, they make me feels happy,” Taw said. “They say, ‘It’s OK my son; you are a man. Never give up in your life and someday you will grow up and know more.’”

By Maria Kalaitzandonakes

Justin • Jan 16, 2013 at 9:21 am

It is shocking the amount of families who do not use english in the household. I know a lot of students that struggle with the same problem as Taw. Many who struggle with language do not like the inability to come up with the word that they are thinking of.

Yazmanian Devil • Jan 16, 2013 at 9:20 am

This is deep

Muhammad Al-Rawi • Jan 14, 2013 at 3:53 pm

It’d look better if the address and numbers were just Photoshopped out. The stark black draws a lot of attention.

Just a thought.