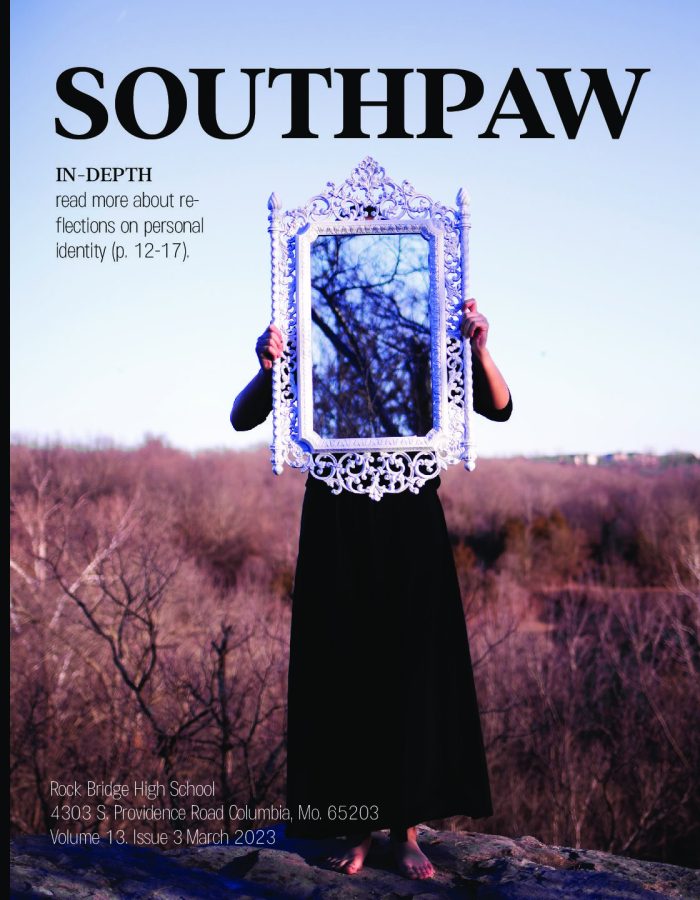

Lost

|

>>Blake Becker Independence pushes people to walk their own road and find their identity. Wandering off the path however, they can become swathed in isolation and depression. Junior Blake Becker talks about his struggles finding his identity. |

>>Adam Schoelz In the hypercompetitive world of academics, some students feel left behind when it comes to choosing careers. And as their high school lives end, these students feel mounting pressure. After the final grades are turned in, they ask, what comes next? |

>>Mike Presberg Nothing rivals high school competition when it comes to producing extreme emotions. The victors emerge jubilant, while the vanquished face bitter disappointment. The defeated speak of their agonizing loss and how they overcame their failure. |

>>Kirsten Buchanan As children grow older, they learn more about the real world and the corrupt. Their mindsets slowly change and, as a result, so does their behavior. |

|

>>Nomin-Erdene Jagdagdorj When young immigrants come to the United States, one of their hardest struggles involves learning English. This language barrier requires students to overcome ignorance from peers and the nearly impossible academic walls. |

Rejection

>>Maddie Magruder Fitting into society is a proven longing. Thus, when adolescents find themselves in situations of isolation, changes can happen within a person — whether for better or worse. |

Memory

>>Sami Pathan A key component of aging is the loss of one’s memory. Through diseases like Alzheimer’s, people forget about loved ones and how to care for themselves. The end result is losing everything one has worked for during his or her life. |

Near-Death Experiences

>>Alyssa Sykuta Whether because of a health problem or an accident, when people face near-death experiences, their perspectives on morality dramatically change. |

Compassion mends mental scars

Start with depression, add self-pity, pepper with arrogance and mix a closed mind filled with conceit. Cover with a cloud of apathy. Presto: the recipe for a loss of reality, respect, dignity and identity.

Start with depression, add self-pity, pepper with arrogance and mix a closed mind filled with conceit. Cover with a cloud of apathy. Presto: the recipe for a loss of reality, respect, dignity and identity.

A large part of my life has been scarred with regret, shame and isolation.

My journey began when I left elementary school feeling like a million bucks, ready to make a grandstand in middle school to lead the pack. But my old friends were not in any of the classes in my new world.

An extreme left-wing environmentalist, I held a deaf ear to others’ ideas. I raised myself an intellectual above others, with my word as truth.

In reality I was in for a world of hurt.

I walked the halls of middle school with a smile rarely crossing my face, trying to always be serious to assert my “coolness.” However, I came off as a short, apathetic whiner. People asked me questions, “Do you have any emotions?” or “Are you a robot?” for valid reasons. I grew to hate school, developing a sense of pessimism, a sailor’s mouth and a sense of loneliness, yet I continued my poor social habits. I labeled those without an obvious liking to me as bad people and insulted those who didn’t agree with me.

I tried turning to my old friends, looking for a sense of belonging and camaraderie. But this fellowship broke as I tainted our friendship with my new behavior and incessant complaining on my school life. They rapidly lost their sympathy as my displays of self-pity and lethargy showed why I was having a miserable time. They shrank from my presence like bats from sunlight. Time we spent together decreased, I realized no one called to hang out. Only I was making contacts. Then I was truly alone.

In eighth and ninth grade I condemned my old friends as traitors and developed a seething hatred for them. I cursed every step they took, grouping them with the people I disliked in middle school. Now, left with no one, I branded myself an outcast, thinking it was a title of individualism. I conjured a place where I was purely innocent while the conformists of society preyed upon my keen intellect. They couldn’t understand my logic. If I found people who didn’t believe in climate change, I would shower them with insults then wonder why they disliked me.

I talked big and made empty threats if challenged or put down; the targeted saw my ruse and pointed out flaws in my physique. I was the victim, they the tormentor, gleefully stomping on my depression and needling at my faults.

I dug a bottomless hole of self-pity, losing any chance of redemption in the eyes of my peers.

My parents and sister sympathized for a long time. They said school life would get better, and I would eventually find people to relate to. Their coddling stopped after two years of the same defeated attitude. Then during the second semester of my freshman year, my mother gave me the wake-up call I desperately needed.

“You’re going to be miserable for the rest of your life,” she said.

It wasn’t the words she said that affected me but instead who said it. Those words came from a person I will love my entire life. The same effect would have come from my father, sister or another close relative because these are all people who love me.

Hearing a voice I trusted, I was no longer lost. I tore down the pride and loneliness, a curtain of self-deceit, to hide any poor social decisions. I felt enlightened and aspired to be a friendlier, better person. I greeted people with a smile, kept an upbeat tone and joked around more.

People saw me in a better light and treated me with more respect as I did to them. They encouraged me to join conversations, happy to have my company.

There are countless people lost in the world, in this school. All have problems they can’t solve alone. It takes one person whom they love to save them from being lost. None of us can make it alone. I won’t be lost again because people care enough to keep me on the right path, and it’s my duty to watch out for those I care for, too.

By Blake Becker

Purity disappears as children grow up

When a 30-year-old man approached her, senior Ngoc Tran tried not to respond. Skittish, the then-third grader ducked away when he talked to her and pinched her cheeks. After he left, Tran realized the encounter had been more than just awkward.

When a 30-year-old man approached her, senior Ngoc Tran tried not to respond. Skittish, the then-third grader ducked away when he talked to her and pinched her cheeks. After he left, Tran realized the encounter had been more than just awkward.

“When I was little, I was really chubby [so] that’s why people pinch[ed] my cheek, so I thought he was just like other people,” Tran said. “When he talked to me, I didn’t feel [anything]. But when he left, I touched my ears, and he had taken my earrings.”

While the robbery disapointed her, its eeriness stuck with her longer than the sting of loss.

The robbery “made me realize that people are not really nice, and sometimes they’re kind of creepy,” Tran said. After that experience “when people [approached] me I had more tension. I was more scared and realized things could go wrong and that the world could be dangerous.”

Tran became more apprehensive of strangers and tried to keep her distance from anybody she didn’t know.

Senior Wednesday Corley, on the other hand, tried to maintain her naivety even after experiencing multiple unethical events. When she heard there was a homicide in her neighborhood, she shrugged the news off. It was the second murder that month in the inner city, but in a place where crime was frequent, it hardly affected the fifth grader.

Crime “never [caused me to be] like, ‘Oh, the world is bad,’” Corley said. “I was just like, ‘Oh, … that happened. This sucks. But oh well. The world’s still a good place.’”

Her nonchalant view changed when a girl her age began to tease her family for no apparent reason. While other crimes had not affected her personally, all of a sudden she was in a situation where she was experiencing immoral behavior first hand.

Corley confronted the girl and told her to stop. Annoyed, the girl told Corley to meet her for a fight. Although Corley came out of the fight physically unharmed, her mindset changed.

“I realized that there’s not a lot of good in the world. I felt betrayed because I hadn’t done anything, and I didn’t want to hurt her, but it escalated to a fight because I wanted to protect what made me happy, even if I had to do something bad for it,” Corley said. “Realizing that I had to take actions like that … just changed me.”

University of Missouri — Columbia doctoral student Benjamin Winegard said in an email traumatic events often open up a person’s worldview. He said most children become aware of evil things around age 12 or 13 because they develop the ability to think abstractly. A young child, nonetheless, can still recognize evil.

“Much evidence suggests that humans come ‘hardwired’ into the world with a moral grammar and that this is refined based on local inputs from institutions, social groups and so on,” Winegard said. “This suggests that children are aware of the fact that the world is an unfair place at a pretty early age. If you notice, very young children have an innate fear of strangers.”

A reality check associated with loss of innocence also comes in non-criminal situations, like it did for junior Matthew Caldwell. In fifth grade, his class began sex education. Not only were the facts surprising and new to him, but after learning about the negative ramifications associated with sex, Caldwell felt his purity slipping away.

“After [sex education] I guess guys started kind of talking differently when they heard [sex] and start[ed] acting differently and started talking more perverted[ly]. They made more inappropriate jokes,” Caldwell said. “You don’t think the same way after guys think like that and talk like that, and you start changing as well with the way they talk, and you kind of want to fit in so you talk that way, too.”

Caught between morality and belonging, Caldwell started acting differently toward girls. Sometimes he treated them better than before and at other times worse, but his behavior was not the only difference; he had to learn how to live in a world where he knew the undesirable parts about sex.

Winegard said most adults try to maintain their innocence and believe Earth is a fair place. He cites a phenomenon called just-world beliefs, where most people are predisposed to think the world is a safe, impartial place.

Just-world beliefs “make us humans blame the victim more often than we should because it reassures us that the world is OK. I’ll catch myself doing it when I read about a guy who got shot in a bar or something,” Winegard said. “Automatically, I think to myself, ‘The guy was probably a worthless drunk who was picking a fight.’ Of course, I quickly correct myself and feel silly for attempting to justify the shooting. Even though we all lose our innocence, so to speak, we still like to keep it as adults. Most people cannot handle the idea that life is truly not fair.”

Corley believes keeping her purity is a task with a simple solution: it is merely a matter of optimism.

“I have a strange feeling that if you look at the bad in the world, you gain more innocence because of it — because you see what happens,” Corley said. “You see how good you got it, and you realize how much bad your life is not.”

By Kirsten Buchanan

Athletes endure devastating losses

Before the 2011 season even began, the RBHS boys soccer team had its sights set on winning the state championship for the first time in school history. With 13 varsity players returning from a team that finished fourth in the 2010 state tournament, both the players and the coaching staff knew the goal was well within reach.

Before the 2011 season even began, the RBHS boys soccer team had its sights set on winning the state championship for the first time in school history. With 13 varsity players returning from a team that finished fourth in the 2010 state tournament, both the players and the coaching staff knew the goal was well within reach.

“The very first practice [assistant] coach [Alex] Nichols came in saying that if we don’t win state, it’ll be a failure of a season. So from the very beginning he had us aiming to be perfect,” senior midfielder Ryan Schmidt said. “We were there to show that a public school in central Missouri can have a team that can compete with all the private schools in St. Louis and Kansas City.”

The Bruins opened the season with games against two of the top teams in the Midwest: Kansas City’s Rockhurst and Illinois’ Quincy Notre Dame. Although RBHS lost both games by one goal, the team proved it could compete with anyone in the state, and perhaps even the country.

It went on to win 24 of its next 25 games, setting a school record for most shutouts in a single season along the way. The team also captured and maintained the No. 1 state ranking throughout the second half of the season.

After defeating their arch rival Hickman High School to win the district championship, the Bruins continued their post-season success by beating Rolla 3-1 in sectionals and Nixa 2-0 in the state quarterfinals.

“The [Rolla and Quincy] games really showed us that if we stuck to our game and played our style, we could beat anybody,” Schmidt said. “We were more confident than we’d ever been, and it felt like we could go all the way.”

But the greatest soccer season in RBHS’ history took an unexpected turn when the team’s dreams of a state championship shattered just six days later.

The Bruins, despite not allowing a single shot on goal the entire game, fell to underdog Oakville 1-0 on penalty kicks in the state semifinal matchup, after Oakville made all five of its PK’s.

“It was honestly the hardest loss that I have ever been a part of as either a player or coach,” head coach Kyle Austin said. “The look of disappointment on the players’ faces after the game was unbearable and gut wrenching. My coaching staff and myself felt so helpless. … We knew there was nothing that we could do or say.”

There are few things as devastating as an unexpected loss, even when it comes to something as seemingly inconsequential as high school competition.

According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, a shocking defeat in athletics can have long-term psychological effects. These include abnormal levels of harm avoidance and severe anxiety, as well as novelty seeking behaviors such as impulsiveness and extravagance.

Although they haven’t experienced effects as drastic as these, the boys and girls show choir “City Lights” suffered severe disappointment after receiving a disheartening blow of their own in their first performance this year.

After evaluating each of the teams at the Pleasant Hill festival in late January, Bruins choir director Mike Pierson told the team it had an excellent chance of placing at least second overall in the competition.

The group’s confidence skyrocketed after RBHS’ all-girls show choir team “Satin ‘N Lace” won first place in the all-female competition. “City Lights” merely had to finish in fourth place to qualify for the finals.

But as the announcer read the names of the top four teams into the microphone, “City Lights” was surprisingly absent.

“We started to hear the other names of the choirs they said,” junior Morgan Widhalm said. “They got to the first place overall, and our name still hadn’t been called. We were so confused. … We were made to believe that we had such a great chance of making finals, and then the rug was pulled out from under us.”

The results devastated the group and in unfamiliar territory; it was the first time in more than six years “City Lights” hadn’t made the finals of the Pleasant Hill tournament.

“There were a lot of sullen faces; people were just [lying] on the ground waiting to go home and just go to sleep and be done with the day,” Widhalm said. “I know a few girls had started crying about the performance, and I know my guy friend had this look, like trying to contain the anger.”

Despite the initial disappointment of losing, however, Widhalm said the experience has actually done more good than harm for the group.

“That was a piece of humble pie. We really realized that we couldn’t just go into the competitions with the mindset that we were [going to] win,” Widhalm said. “We [have] to work our butts off, and I think it’s made us a lot more dedicated to our rehearsals. … It really brought more energy back into the group.”

Unlike show choir, there was finality to the soccer team’s defeat. A loss in the semifinals meant the Bruins had no chance of achieving their season-long goal of winning the state championship.

But even though they fell short of their dream, the players decided that ending the season as a team and as a group of friends was still of utmost importance.

“In the end I turned the game over to the seniors and asked how they wanted to end their careers,” Austin said. “And in a true reflection of their character … they chose to embrace all of their teammates and share playing time equally so that everyone shared in the glory and had their moment to shine at the final four of state.”

The Bruins won the game and finished with the best record in RBHS’ history. But somehow the outcome of the season didn’t matter as much to the players as had imagined. Instead, what seemed important was the friendships gained and the lessons learned.

Schmidt believes the disappointing finish — and the season leading up to it — has done anything but damage him psychologically. In fact, he said it’s given him a more thoughtful, mature perspective not only on athletics, but also on life.

“I realized that you don’t just look at your outcome; you have to look at the personal goals you achieved throughout the season,” Schmidt said. “I had to battle through injuries, so I learned a lot about myself there, and as a team we just really bonded. It’s not really about the end result; it’s about the road you take to get there.”

By Mike Presberg

Lack of acceptance raises questions about individual worth

Three little girls run around the playground, portraying cartoon characters with enthusiasm. Energetic boys play freeze tag, posing in goofy stances. All seems fine on this kindergarten playground. But in the corner stands a little girl, all alone. No one asked her to play.

Three little girls run around the playground, portraying cartoon characters with enthusiasm. Energetic boys play freeze tag, posing in goofy stances. All seems fine on this kindergarten playground. But in the corner stands a little girl, all alone. No one asked her to play.

Senior Maddie Hicks said she was this little girl.

“I was really, really skinny and my teeth were really messed up,” Hicks said, “and I had glasses, so I had the complete odd-kid-out look.”

Through elementary school, she didn’t think she fit in with her classmates. Her reading level was slightly above the others, and combined with her appearance, she said the kids didn’t know what to think of her.

The differences continued through middle school, too.

“I definitely did feel like I wanted to attempt to be like [my classmates], and I wanted to attempt to have their normalcy,” Hicks said, “and I tried, but it didn’t really work. And it was too hard to be what their idea of what I should be like was. So I kind of gave up.”

Advanced Placement Psychology teacher Tim Dickmeyer said the human race finds safety in groups, making belonging in society a pathological need. Twentieth century psychologist Abraham Maslow created a pyramid that put the need for belonging directly after physiological satisfaction — water, food and air. But Maslow’s theory also stated in some cases a person’s need to belong can surpass his need for safety.

“We all react to rejection in different ways,” Dickmeyer said. “Some people express their rejection by becoming hyper-aggressive. Some people direct their rejection inward and become depressed.”

Senior Haley Canada said she experienced loneliness nearly her entire life. Even before telling people she was homosexual at age 13, she didn’t think her peers accepted her. In eighth grade Canada’s peers told her she needed to act more “girly.” In an effort to appease her friends, she bought skirts, painted her nails and did her hair every day.

“Everybody kind of bought into [my behavior]. Everybody thought, ‘Oh, she’s finally normal. She’s finally acting how she’s supposed to,’” Canada said. “But deep inside, I was like, ‘This is absolutely ridiculous.’ And I felt like if I started acting like who I wanted to be, people would automatically shun me.”

After Canada came out, she had no one to relate to and felt even more alone, questioning life. She thought if she wasn’t alive, a load would disappear from the shoulders of her parents and friends.

“I lost myself,” Canada said. “I didn’t know who I was, and I was trying to be something that I truly wasn’t just to make other people happy when, in reality, I was absolutely miserable.”

From ages 13 to 15, Canada harmed herself as a way to escape. She felt she had no one to turn to for advice, so this was the only way out she could find. Many adolescents around the U.S. find themselves in this situation. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 666,000 emergency department visits in the United States in 2008 solely because of self-harm.

“At this one point, right before I was about to do something” life-threatening, Canada said, “I realized I have so much potential in life, and with potential, there are so many opportunities.”

One way Canada has stayed true to herself is by expressing herself through music. If she ever feels stressed, music is her solace.

“I’ll just get my guitar out and strum a few chords, or I’ll write a few songs,” she said. “That’s the main way I get out my emotions because sometimes it’s very hard to say what I feel.”

Canada also expresses herself through tattoos; the symbols and phrases serve as constant reminders of the journey in life so far. One below her neck that says “Breathe” brings her comfort; when life begins to overwhelm her, she can look to the tattoo to remember everything will work out.

“The reason I got it is because you [have] to look around and see what you have in front of you,” Canada said. “Don’t look too much into the past. Don’t look so much into the future. … Don’t get so caught up in trying to be something you’re not. Just do the simple things. Take it one breath at a time.”

Snide comments are enough to work someone up, Hicks said. Some of her teasers’ comments really got to her. While she tried to let them roll off her back, there were some she just couldn’t shake off.

“I’m not that girl who’s like, ‘Oh, I’m so beautiful, and I’m so pretty,’ but I know that I’m not a sea monster,” Hicks said. “When people criticize my intelligence or my own desires or interests, I tend to question them more on that and question myself more. But by doing that, I understand myself a little bit more too.”

When she looks at the past, she doesn’t remember the teasing from elementary school. It may have hurt at the time, but she’s learned a valuable lesson from her high school years. She doesn’t even talk to the teasers now.

“Sometimes I see them in the hall, [and] I don’t know if some of them even made it to high school, to be honest,” Hicks said, “so [the teasing] doesn’t bother me, and I know I have a future ahead of me and a lot of things that I don’t think they’ll ever be able to take away from me, so I just kind of don’t care anymore.”

Like Hicks, Canada has learned to care little about what people think. Their opinions aren’t important, she said. She knows how to express herself, and if certain people don’t agree with it, she can always find someone else who will.

“I’ve come to accept the fact that people are obviously not going to understand me, and I can’t really change their minds,” Canada said. “I just have to be able to be happy with myself and who I am and just accept myself for who I am.”

By Maddie Magruder

Memory loss degenerates a person’s life

Like so many from his generation, Roy Hayden joined the U.S. military to fight in Vietnam. He was only 22 at the time, fresh out of college. Hayden was an armor crewman; he pumped grease into the wheel hubs of different tanks to help everything run smoothly.

Like so many from his generation, Roy Hayden joined the U.S. military to fight in Vietnam. He was only 22 at the time, fresh out of college. Hayden was an armor crewman; he pumped grease into the wheel hubs of different tanks to help everything run smoothly.

For Hayden those days are long past and slowly fading.

In December 2009 doctors diagnosed Hayden, a Columbia resident, with the beginning stage of Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia. He had been noticing anomalies in his behavior for months and finally visited a doctor after increased pressure from his wife.

“Probably the biggest thing for me was that I was increasingly irritable; [my wife] was noticing my anger get to excessive levels — all for things that weren’t supposed to make me so angry,” Hayden said. “I thought at the start that it was just aging, but it was there for long enough that my wife made me get checked up.”

The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program concluded in a 2009 study that 36 million people worldwide suffer from Alzheimer’s, and by 2050 that number would be 115 million. A sub-group of the disease, early-onset Alzheimer’s, has recently been on the rise, with rare cases branching from the usual 60-year-olds and affecting people in their twenties.

Geriatrician David Carr, M.D., said many early signs of dementia are mistaken for natural results of aging or stress, similar to Hayden’s case.

“Obviously, just as in any other type of illness, the earlier you catch the problem, the greater the chance that we can slow the spread and give the patient a better quality of life for a longer period,” Carr said. “Because there isn’t a cure to Alzheimer’s yet, we just do our best to slow everything down, to slow the loss of memory and some daily living activities.”

Alzheimer’s disease affects newer memories and facts to a greater degree than old facts or memories. Hayden remembers driving to places only to forget his destination for a brief time and then having to stop to recall.

“I was having spells of driving down a familiar street and suddenly being unable to recognize where I was going, whether I had to take a right up ahead or go straight,” Hayden said. “I would eventually recover, but this kind of thing happened really often. … It was like being randomly placed in a city where you didn’t know anything.”

Alzheimer’s patients face increased memory and motor degeneration as time passes, working their way from stage one — mild symptoms such difficulty with movements and forgetting recent information — to stage four — severe dysfunction where the victim is completely dependent upon caregivers. Carr said the disease can often take a severe toll on family connections because of the caregiving problems as well as the overall loss of relationship skill patients exhibit.

“It’s hard on children of the patients who aren’t recognized anymore [and] hard on the caregiver who may not feel as attached or upset they have to work as hard as they do. … Caring for a stage four patient could be an occupation in itself,” Carr said. “I’ve even seen a case where a patient in a nursing home forgot who their spouse was, so they started to vie for a new partner. … This was all in front of the spouse who came daily to see them. You can imagine how heartbreaking that was.”

Seven years ago, doctors diagnosed senior Paige Bocklage’s grandmother with Alzheimer’s disease. Since then her memory has slowly broken down to stage three, where sometimes she cannot remember questions or faces and occasionally talks unintelligibly.

“It is hard watching my grandma on one of her rough days, like when she can’t remember why we are there for coffee and why my grandpa [went out],” Bocklage said in an email interview. “I definitely treat my grandmother differently. She is very fragile and will walk off in search of my grandpa if you are not watching her. So things like always holding her hand when we are walking places are things we do now.”

The memory loss has been tough on Bocklage’s grandmother as well. Before being diagnosed, she lived on a farm with her husband in eastern Missouri, caring for an apple orchard and farm animals. The Bocklage family has since needed to relocate her to the Terrace, a retirement community for seniors, to assist in the ever-increasing care needs.

“She knew when she couldn’t remember things and still at times does this. It’s caused her a lot of suffering, things like when she [can’t] remember how to do simple tasks, such as baking,” Bocklage said. “We also have to act like nothing is wrong because she feels like she is a burden, and so we just constantly act happy around her.”

Between 2000 and 2008, the National Center for Health Statistics reported the percentage of deaths because of Alzheimer’s disease increased by 66 percent. Both Bocklage’s grandmother and Hayden struggle with the knowledge their illness is incurable and will one day lead to their deaths.

“I’m fortunate because I’m still not in the late stages yet,” Hayden said. “But it’s scary, and I try not to think about it, but there will come a time where I’m completely unable to function on my own, recognize the people that I love. You get to that point, and you’ve lost everything you spent your life working for.”

Though the ADRP concluded the average patient survives four to eight years, the mood is not always sullen. Bocklage and her family have enjoyed numerous lighter moments with her grandmother because of her memory loss, including one where lipstick wound up in her grandmother’s hair.

“I thought I had been seeing things because my grandma had pink hair in the front. When we got up to leave I leaned over to my mom and asked her if she saw it, too,” Bocklage said. “My grandma didn’t know how, but she had colored her hair pink. We believe she forgot how to put on lipstick, but she knew she was supposed to be using it, so she put it in her hair.”

Though for many people the loss of memories can signify a slow deterioration in quality of life, a solid support system can ease the loss, Carr said.

“Luck always plays a part in an illness like this where there are few known causes or treatments, but catching it early is always a big help,” Carr said. “By no means is memory loss something easy to deal with, but with the right help it becomes easier on everyone involved.”

By Sami Pathan

English inhibits foreign students’ success in class

As a new student at West Junior High School, senior Hanan Nour cussed her way to a suspension. Her profane language came not from bravery or daring, or even violence or anger, but from simple frustration. It was really a misunderstanding between a young immigrant and school administrators.

As a new student at West Junior High School, senior Hanan Nour cussed her way to a suspension. Her profane language came not from bravery or daring, or even violence or anger, but from simple frustration. It was really a misunderstanding between a young immigrant and school administrators.

The ordeal began after lunchtime, when a tearful Nour chose to sit in an empty cafeteria rather than aimlessly drift through the hallways. After all, she thought, her attempts to find her classes had rarely succeeded before. And if she happened to find her class, the teacher would undoubtedly reprimand her for her tardiness. And somehow, if she arrived to class on time, she hadn’t mastered enough English to communicate effectively with her teacher or classmates.

So this time, she didn’t want to bother with the embarrassing, fruitless process at all.

But the school’s administrators didn’t know the grief Nour endured just to get through her day. They simply saw a teenager refusing to go to class. So they took her to her guidance counselor, who also failed to understand what Nour was experiencing.

Finally, Nour spoke the only English words she knew well enough to use as communication tools. Coupled with her frustration, her curse words came out as insulting refusals to cooperate with the administrators.

“I said something terrible. I didn’t mean it that way because maybe I was just so mad,” said Nour, who is now a senior at RBHS. “I knew every single bad word because that was the first thing you learn.”

Born in Saudi Arabia, Nour moved with her family to Syria for a year. In Syria Nour attended a private school, where she learned in Arabic, the language she had always spoken, so there was no reason to pay attention in the English class her mother had insisted she take.

But then in 2007, she came to the United States, where she desperately wanted to be able to communicate but couldn’t. Suddenly, school not only turned into an uncomfortable labyrinth of dizzying doorways and hallways, but also of strangers and their bizarre language. Just trying to get teachers and other students to understand what she said was a struggle.

“We came here, and everyone spoke the same language, and you’re the different one, and you have to face it,” Nour said. “I never knew how to explain things. … You feel so bad because you want to tell them something, and then they can’t understand you. [This] was one of the most horrible things I’ve ever been in.”

The language boundary became even more maddening when teachers deemed Nour stupid or dumb when she could not communicate her understanding of class material, she said. Nour would stand in front of her teachers, gesturing explanations, or she would use a translator. English Language Learners teachers also helped her communicate with her other teachers. Nour said ELL teachers’ experiences with foreign students made them more understanding and easier to communicate with.

ELL teacher Peggy White, who has taught at RBHS for six years, tries to make these special connections with her students. She even attempts to build personal relationships with their families and encourages her students to bond with one another. Ultimately, White aims to help each student learn English and graduate high school.

“We would like to see them get a high school diploma in four years, sometimes five years — it’s almost impossible. But if they don’t get a high school diploma, they’re not going to have a good future here,” White said. This is “a challenge because they are learning a new language, and they have to be able to read at a high school level immediately.”

The three levels of ELL classes at RBHS set specific goals, with graduation as the ultimate destination. This tangible purpose became the end of the maze that was high school, even if it was a hard one to reach. White’s dedication to helping each of her students succeed has motivated senior Haneen Alibadi whenever she has been unsure if she will overcome her difficulties in the United States.

“I have to tell myself, ‘I have to do this.’ … I know I have to do it by myself,” Alibadi said. But “every time I get a bad score on my paper, like in U.S. or World Studies or ELL class, I just say, ‘OK, I give up. I can’t do it.’ But then Ms. White, she [is always willing to] motivate us, encourage us.”

But sometimes, White’s enthusiasm isn’t enough. American students frequently overlook ELL students, White said. Even if the U.S. natives aren’t directly bullying them, the disregard makes ELL students feel more misplaced in a classroom where everyone else seemingly belongs.

“The biggest problem for them is that U.S. students just ignore [ELL students]. And that’s hurtful, and it doesn’t help them academically. … They sit in a class, and they’re silent. And U.S. students don’t encourage them to work with them in groups,” White said. “It takes a lot of patience to have a conversation with someone who is not proficient in English. … And I think U.S. students don’t feel comfortable giving English learners the wait time that is needed.”

To help ease the transition to English-heavy classes, RBHS places ELL students in classes like P.E. and art, White said. They also take keyboarding to learn how to type on a QWERTY keyboard and to master the alphabet. For Nour classes that required fewer language skills became a solace amid a torrent of confusion.

“Math was one of the easiest. I believe math does not depend on what language you speak. To me it’s kind of a different language,” Nour said. Math is “something you think about, and you work it out. And then when I started working it out, my teachers would know that I know something. I’m not dumb. I’m not stupid.”

Math was senior Minsoo Soh’s favorite subject, too. Born in Tokyo, Japan, the Korean student came to America two years ago. Despite having studied in the United Kingdom and Colorado, Soh faced some of the same difficulties as Nour. Math provided the simplicity he could not find anywhere else at RBHS.

“In Korea the questions were not direct. Here it’s really straightforward,” Soh said. But with writing, the opposite was true because American writing is “really creative, and you have to think a lot. So I need a lot of time to think about [it] because I have to think first in Korean way, and then I have to write it in Korean first. And then I have to translate all of that writing into English. So I need more time, more effort.”

Korea’s focus on strict, tight schedules contrasted starkly with America’s concentration on freedom and creativity. But cultural differences extended past school life. They also made it difficult for Soh to make friends at RBHS.

“I usually don’t speak with people I don’t know. In Korea if you don’t know each other, you don’t talk [to] each other,” Soh said. “Americans are really friendly, and they talk, even though they don’t know each other. … I realized that’s a part of American culture. So first … [I had] trouble making friends with that kind of mind, like not speaking with people.”

Letting go of Korean cultural norms like this one allowed Soh to accelerate his assimilation. Alibadi’s ties to her native country, however, kept her from wanting to adapt fully. Alibadi, who emigrated from a war-torn Iraq in 2010, came to RBHS to surround herself with native-speakers of English. But her desperation to learn English and adapt to American culture directly conflicted with the anger she had felt back home against the United States. Originally, she hoped to gain as much as she could from the United States without betraying her loyalty to her home.

“I know I have to learn, and I have to get [a good education], and then I’m going to go back to my country,” Alibadi said. “I have to get something good for myself, even if it’s from my enemy or my friend.”

But as she lost herself in the struggle to learn the language, Alibadi befriended Americans and adapted to American culture. In fact, regardless of whether it was with an American or an Iraqi, friendship was a constant when everything else about the two cultures was different. She also learned Americans are much more accepting than she had expected; their judgments of her are based not on her hijab or her religion, she said, but her personal character.

While this realization alleviated her feeling of being lost in a strange place, she is afraid her friends back home will not understand her acceptance of and adaptation to American culture.

“The only thing I [am] worried about all the time [is] that one day, my friend in Iraq [will say], ‘You just left Iraq, and you are going to a country that just destroy[ed] our country,’” Alibadi said, “and I don’t have any answer to that. It’s hard.”

Even though Soh had none of the original resentment Alibadi did, learning American customs was still gradual for him. Knowing other Koreans eased the transition, he said. It was easier for Soh to make Korean friends because he could communicate with them easily. He said they acted as bridges, giving him advice and introducing him to Americans.

Arabic-speaking students comforted Nour for the same reasons. But she also found it easier to befriend other foreigners, regardless of their nationalities or level of English. She said she had more in common with them than with her American peers.

Still, ELL students learn to gradually reach out to American students, White said. She said enduring the struggle and finding the way to learn and communicate in an entirely different language ultimately builds the characters of ELL students.

“Tenacity,” White said. “They learn tenacity.”

By Nomin Erdene-Jagdagdorj

Close encounters with death bring new perspectives

The day started out normally for junior Alex Jones. He drove down Route K with his girlfriend, junior Catie Rodriguez, the morning of Aug. 18.

The day started out normally for junior Alex Jones. He drove down Route K with his girlfriend, junior Catie Rodriguez, the morning of Aug. 18.

But when Jones collided with a dump truck while he turned onto Old Plank Road, the ordinary morning escalated to a chaotic blur.

“I didn’t really feel any pain there because I guess adrenaline kicked in,” Jones said. “I was mainly just scared because I thought [Rodriguez] was dying. … I didn’t know what was going on because I never even saw the truck.”

Jones escaped the crash with some burns, while Rodriguez’s injuries were more extensive — a broken ankle, femur and pelvis. Jones struggled to watch her endure the outcomes of the accident.

“I just remember I was at the hospital for a long time, day and night, for probably a few weeks,” Jones said. “She had to give up a lot of her life, and it was really hard for me to see her go through that kind of stuff.”

While evidence of his own injuries fades, the accident still haunts Jones. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 39 percent of car crashes are fatal for occupants of passenger vehicles. Jones marvels at his and Rodriguez’s survival six months later. The incident left him with a new appreciation for life.

“The biggest thing [the accident] did for me was move me closer to God because [it’s] a miracle that we are alive. I dream about it every night, and there’s not a time that I get in a car that I don’t think about it. It really matured me as a person,” Jones said. “A bunch of teenagers just … sneak out and go drive, or drink and drive, and they don’t realize how quickly your life can change. I didn’t intend for it, but just within a second or two seconds my whole life changed, and I could have killed my girlfriend or killed myself or killed the truck driver without any intention.”

Revelations vary by experience, according to research by P.M.H. Atwater, Ph.D. She said some survivors hold stronger beliefs in God, like Jones. Some might sense renewed humanity in others, all depending on the experience itself. Jones’ life-altering event took place in an instant, but others’ encounters with death are more prolonged.

From birth, junior Stephanie Spratt has battled a weak immune system. Her freshman year, Spratt developed severe rheumatoid arthritis, along with myoclonic seizures, shock-like jerks of a group of muscles. After hospitalization in St. Louis, Spratt returned home and had several blood tests. But that summer she endured a worse bout of problems — this time raising questions in Spratt’s mind of her survival.

“I stopped being able to eat,” Spratt said. “I lost 30 pounds, and I was in the hospital again because I couldn’t keep anything down. My bone density went down, all my vitamin levels went down and [the doctors] thought I was going to die.”

Hoping to keep her alive, doctors performed more tests. Ginger Spratt, Stephanie’s mother, said the inability to diagnose Stephanie sustained a great amount of worry.

“We actually didn’t know [the diagnosis] until last year,” Ginger said. “It was expensive, and it was very stressful. We had many [doctor] visits. We would deal with one thing and then something else would come up. … It was very frustrating not to know what was really going on.”

After months of uncertainty, it turned out Stephanie was the one out of 133 with celiac, according to the Celiac Disease Foundation. Celiac damages the small intestine, preventing absorption of important nutrients. The damage results from a reaction to gluten, found in wheat, barley and rye. Avoiding these resolves the problem for most people. The disease isn’t usually fatal, but Stephanie knows when she eats gluten because she immediately gets sick.

Stephanie said her family had to make the most adaptations to suit her needs. Ginger now makes all of the family’s food gluten free, but Stephanie also said the expensive hospital bills and constant attention she has needed have taken up a lot of her family’s time.

Stephanie’s health took an unexpected turn last June when doctors found a tumor in her breast, ending the relief that came with the celiac diagnosis. Although she had surgery, the angst only ended weeks later when they learned the tumor was benign. But this past January, doctors caught two more tumors, bringing about yet another period of anxiety and apprehension.

“Waiting to find out, ‘Is this cancer?’ was really stressful because [the tumor] looked like cancer on the screen, but you don’t know until you get it out,” Stephanie said. “So with the [tumors] that are in there now, we won’t know until we get them out. We’ll just keep our fingers crossed.”

As health problems continue to test the Spratt family’s fortitude, Ginger said the experiences have only made them “a more caring and compassionate family.” Stephanie believes the family is more united than before the discovery of her disease.

At times she feels sick or needs to go to the hospital, but she would rather be left alone, which sparks disagreements with her parents. By pushing through each argument and life-threatening experience, however, Stephanie thinks her medical journey has given her a new appreciation for her family, strengthening the bonds between them. As she once again faces the unknown with the potential malignancy of her tumors, Stephanie believes both she and her family can remain strong.

The experiences have “almost brought us closer in a way,” Spratt said. “We learned that you don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow, so you might as well be the family that you want to be today.”

By Alyssa Sykuta

Graduating seniors try to find career, life after RBHS

Junior Theo Choma’s future is a clean, well-defined place. Choma knows exactly what he wants: to join the Army Corps of Engineers.

Junior Theo Choma’s future is a clean, well-defined place. Choma knows exactly what he wants: to join the Army Corps of Engineers.

His path is well lined — he wants to attend the University of Missouri-Columbia for a degree in engineering, and he is certain he wants to join Reserve Officer Training Corps. His path is also well trod, as both his father and grandfather served before him.

Not everyone is lucky enough to have a plan.

Senior Ukiah Johnson, for instance, has struggled to find his true calling. For him, school has been a stumbling block as he realized nothing really interested him.

“I’m mediocre at everything, and there’s no one thing that comes out and is like, ‘Hey, come do me,’” Johnson said. “I’m not really good at anything.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, around 68.1% of high school graduates were enrolled in college in 2011, but the number with a career in mind is unknown. Johnson said for him and many of his friends, that career is still a mystery.

“I don’t really feel any pressure, which might be part of the problem of why I haven’t figured out what to do with myself,” Johnson said. “I’ve had talks with people about how they have no idea what they want to do with themselves, either.”

Johnson said the main thing holding him back is his own brain; he cannot bear to fail. This fear of failure, he recognizes, has strangled many opportunities and has left him stranded, unable to find a passion.

“I realize it’s a skill, and it takes time to get good at, but I don’t like doing things I’m not good at,” Johnson said. “I don’t ever develop a skill, and it’s just a vicious cycle.”

Senior Dakotah Cooper has a different problem; he had to give up a dream. At 12, he made his first pie at Thanksgiving and fell in love with baking. In high school, he took an interest in culinary arts and was even accepted to Johnson & Wales University in Denver, a school that specializes in culinary degrees. The costs of such a journey, however, grew prohibitive, so Cooper abandoned his dream of baking for the film program at MU.

“A lot of it was distance away from home and just financial stuff,” Cooper said. “I looked at my opportunities here, and the film program caught my interest because it’s the perfect balance of what I do on a regular basis here at Rock Bridge, writing and acting, so why not?”

Cooper said he doesn’t see MU as a negative turn, however. After all, career changes happen often — the average is seven to 10 in a lifetime according to the BLS.

“Life’s full of wrong choices because once you’ve made a mistake you know not to make that mistake again,” Cooper said. “And I’ve already done it, so it’s all good.”

Senior Andrew Belzer is scared of the wrong choice. His philosophy is that college, not high school, is the place to decide what to do with one’s life. If he decides, Belzer said he will feel trapped by his choice.

“I don’t want to get pinned down this early in life,” Belzer said. “If I choose one career path right now, one option, I’ll be stuck with it for at least a few years if not the rest of my life, and I don’t want to do that until I’m sure about what I’m getting into.”

Counselor Jane Piester said his is a fairly common mindset among both seniors and juniors. While the guidance department’s goal is to make sure every student has a plan for after high school, Piester said students can feel very nervous about what comes next.

“I think students that don’t leave here with some pretty specific plans and goals maybe feel a little more fearful,” Piester said. “Fewer of them know exactly what they want to major in, what they want to study and where they see themselves five years from now.”

Belzer said even though he doesn’t have a career

plan, he’s fine with the uncertainty. Despite not having a major in mind, he feels he can make a good decision on a college with other information.

“I look at where I know people, what I’m familiar with, what I’m comfortable with,” Belzer said, “just somewhere where I can be independent but also somewhere where I have a lot of choices.”

Despite Belzer’s positive attitude, Johnson said not having a plan has many downsides. For him, the lack of a plan has caused enormous stress.

“I’m super stressed about the fact that I don’t have a plan and don’t have any idea with what I’m going to do with my life,” Johnson said. “I’m afraid of ending up fat on a couch in my parent’s basement.”

The quest to find life after high school is not an easy one. Students such as Johnson struggle to find the balance between success and failure, and like Cooper, many must make tough choices that will affect the rest of their lives.

Belzer, though, is happy to let the experiences come.

“I know I want to do something I enjoy, and I think I’ll be able to find that pretty quickly,” Belzer said. “I’m pretty positive that I can get a decent start in the world, even if it’s not at an amazing paying job.”

By Adam Schoelz