A “Garden of Eden” found its place in the center of St. Louis County, and its name was Howard-Evans Place. The neighborhood housing dozens of middle-class Black families lay on twenty-two acres of land at what is now the intersection of Eager Road and Brentwood Boulevard in Brentwood, Mo., and its small yet well-kept houses were a testament to its flourishing working class population. Now, The Promenade at Brentwood — a 337,800-square-foot retail property serving affluent Brentwood and Clayton residents with a larger-than-life Target and other commercial facilities — exists where these families once lived.

Those who called Howard-Evans Place home in the early ‘90s were grandchildren and great-grandchildren of African Americans from the Deep South and Missouri who moved to the area for work at the Evens & Howard Fire Brick Co., which built housing spaces in nearby Howard Place for their workers in 1907. A subdivision called Evans Place was eventually built alongside Howard Place, and the two combined to become Howard-Evans Place — a town which remained economically stable for decades, had low unemployment and was largely made up of Black physicians, attorneys and government workers.

For years, the community resisted anti-Black efforts in the Greater St. Louis area: residents fought a county proposal to destroy 52 homes for new highway ramps in 1977, resisted an attempt to extend Highway 40 that would have demolished 105 houses and two churches in 1988 and curbed a plan to displace hundreds of homes through the addition of a second MetroLink line in 1993, along with others. In 1995, however, a proposed buyout by the Sansone Group prevailed, displacing Black families in the same manner in which African American neighborhoods in Clayton, Mill Creek Valley and more were treated. The then $3.6 million property was soon valued at $30 million within a few years, and the community once known for tight-knit single-family homes and duplexes was now admired for its luxury apartments and high-end markets.

Few traces of Howard-Evans Place remain, and the Brentwood School District is now composed of around 800 majority wealthy, white students. The assessed property value for each of its students is about $579,000, according to a report titled “Assessed Valuation per ADA for 2022-2023” by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), the fourth highest among all districts in the state. It champions a 93.1% score on the Annual Performance Report (APR), a yearly district evaluation assessment led by DESE. Just ten miles north of Brentwood lies the Normandy Schools Collaborative, a majority Black school district with an assessed valuation of just $138,274 per student and an APR score of below 55% for the past two years, placing it on provisional accreditation.

Almost all of the Normandy Schools Collaborative’s students qualify for free and reduced priced lunch (FRL), while only 15-20% of the Brentwood School District’s do, according to a school finance report published by DESE. Since Missouri’s formula for school funding increases allotted state funding for high FRL rates, the Normandy Schools Collaborative should ideally receive more money per-pupil than Brentwood to account for these disparities. This, however, could not be further from reality; according to a report on per-pupil expenditure by building published by DESE, Brentwood spends around $13,472 more per student than Normandy. This disparity is purely due to the Missouri school funding formula, which favors Brentwood for its greater property values.

Labeled as “urban renewal,” the systematic upheaval of low-income communities initiated by both public and private means disproportionately targeted people of color. One could say that these housing trends were more classist than racist, but when race so clearly correlates with wealth in an area, it is clear that policies that do not acknowledge that are inevitably racial. The Black families coerced to move from their historical, flourishing communities are now once again facing structural anti-Blackness in the American educational system. The Foundation Formula, which Missouri uses to calculate state funding, perpetuates long-standing socioeconomic inequalities through its vehement focus on property tax, attendance and other factors that often correlate with race and class. The lack of initiative by Missouri government officials to reevaluate how this formula corroborates practices inextricably tied to the destruction of historically Black neighborhoods and racist housing policies demonstrates how, in urban areas like St. Louis, segregation continues to thrive.

The Foundation Formula explained

Since the 2006-2007 school year, school funding in Missouri has been a student-based formula, meaning that schools are funded student-by-student instead of purely from property tax. The Foundation Formula is as follows: weighted average daily attendance (WADA) times the state adequacy target (SAT) times the dollar value modifier (DVM) minus local effort equals the amount of money given to each school district by the state. The baseline cost of educating a student without special needs or established additional services is the SAT, and multipliers accounting for the cost of FRL, individualized education plans (IEP) and English language proficiency (ELP) programs are applied to the WADA. Using school year and summer school attendance data, the ratio of hours attended to the total possible days becomes the foundation for the WADA, and a student is considered “one student” only if they attend at least 90% of the possible days. The DVM adjusts funding based on the value of a dollar in an area, so areas where the cost of living is higher will receive more, and the local effort is calculated through property tax.

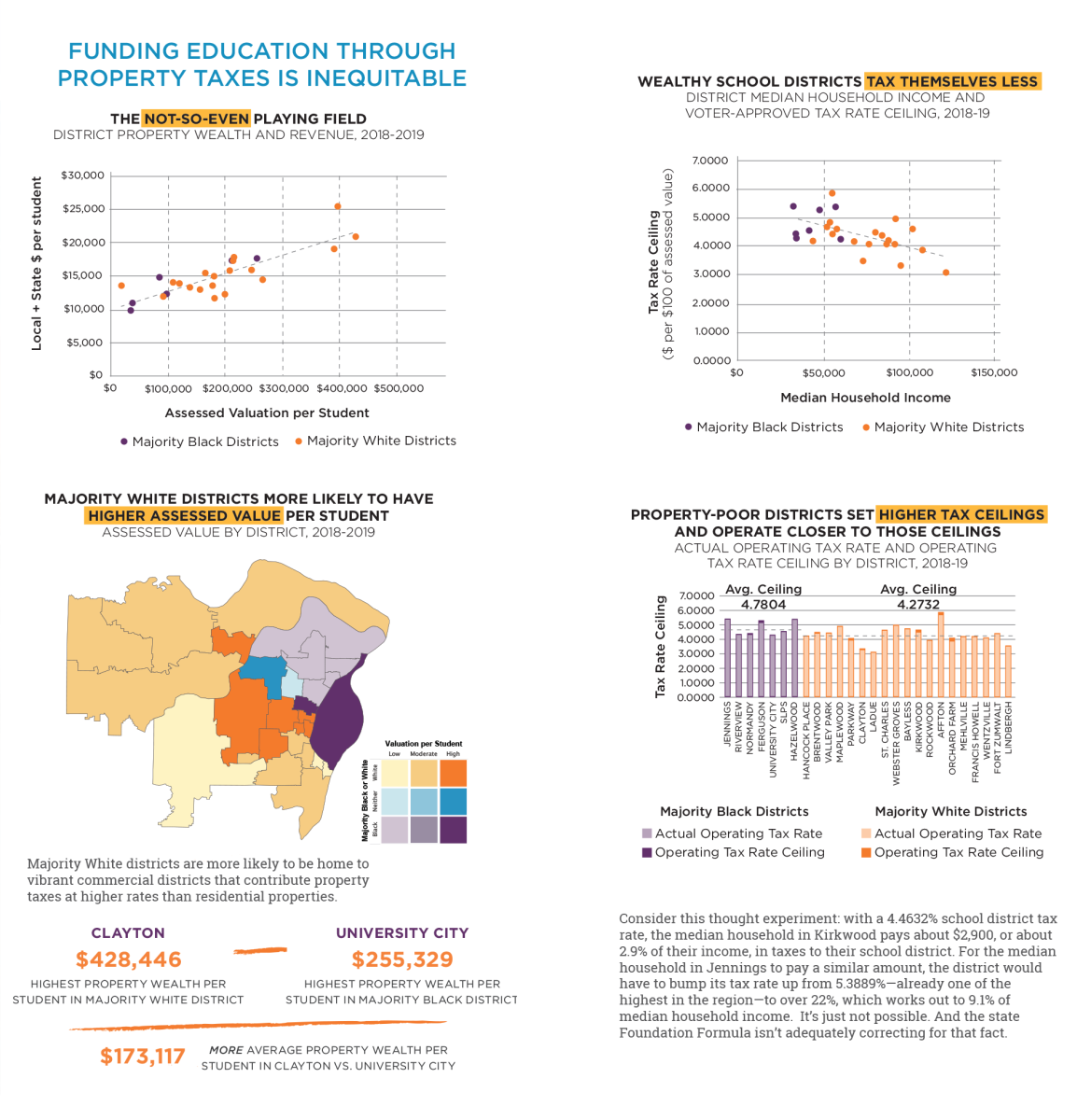

Only around 31% of school funding comes from the state in Missouri, putting it in 49th place in the nation for the amount of state revenue allocated to public education funding. On average, predominantly white districts in St. Louis received $1,648 more in funding per-pupil in the 2018-2019 school year than majority Black districts, and the highest spending majority white district spent $8,412 more per student than the highest spending majority Black district.

Furthermore, majority Black districts typically receive a larger percentage of their funding from the state than their white counterparts. Due to the recession in 2007-2008 and a reliance upon funding from the Missouri Lottery, a state-run lottery, to cover the gap made by revenue re-allocations, the Foundation Formula has only been fully funded three times within the past 18 years, and it fell short by $123 million during the 2020-2021 school year due to COVID-19 disproportionately affecting predominantly Black districts.

Since state funding is volatile, the most reliable source of funding for schools is local property tax revenue, but considering the stark differences in per-pupil expenditures for students living just miles away from each other in St. Louis, the metric itself is intrinsically flawed. The storied history of segregation in St. Louis has been amplified by white flight, the racist implementation of the interstate system in the ‘50s and ‘60s and the systematic upheaval of Black neighborhoods, effectively lowering the value of property in parts of the metro area with large Black and brown populations.

The history of property in the U.S. is racist, the Foundation Formula exacerbates its effects

St. Louis has grown more segregated over the past 30 years. One can quantify segregation with the dissimilarity index (DI), which “measures the percentage of a group’s population that would have to change residence for each neighborhood to have the same percentage of that group as the metropolitan area overall.” This value ranges from 0.0, or complete integration, to 1.0, or complete segregation; the tri-county area (St. Louis City, St. Louis County and St. Charles County) has a DI of 0.674, according to the 2020 census, meaning 67.4% of white and Black residents would have to move neighborhoods (and subsequently school districts) for each to represent the underlying population. In 1968, during a time when many schools were not forced to integrate yet, the national DI was 0.80 — this suggests that even with reintegration measures having been emplaced 70 years ago, segregation in St. Louis is solidified through how Black individuals have been forced to settle.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), a New Deal-era agency that facilitated the construction of houses by insuring banks and mortgage companies, aimed to help all Americans find housing. The way its housing policies were carried out, however, was deeply racist. The FHA and similar government initiatives, like the GI Bill, upheld anti-Blackness on a structural level by primarily assisting the development of a white, suburban middle class as white, urban St. Louis families left for St. Louis County in what is now called “white flight”, depopulating the center of the city. African Americans were often not eligible for FHA-backed loans, and segregation-enforcing housing was secured through individual real estate agencies explicitly restricting the “selling, conveying, leasing, or renting” of property to Black people. Even though racist housing policies were deemed unconstitutional in 1948 by the Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kraemer, the decision did not curb private and implicit government efforts to maintain segregation in St. Louis. Racism became a business — as long as those in power wanted segregation, it would continue to flourish.

The interstate highway system, spearheaded by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the ‘50s, displaced millions of African Americans across the country. Local officials typically determined where highways were to be built, and they were often constructed through majority Black, low-income communities seen as “less valuable.” Interstate 55 destroyed the Black neighborhood of Pleasant View, and Interstate 44 displaced Black families from The Hill. Efforts to redevelop or gentrify St. Louis came with scrapping Black neighborhoods, with 20,000 Black families being forced to move when St. Louis purposefully destroyed Mill Creek Valley, along with parts of Meacham Park, North Webster and Elmwood.

A society which is separate will remain unequal until adequate, intentional measures to combat segregation are taken. In 1983, 23 districts from across St. Louis acknowledged this and agreed to form the Voluntary Interdistrict Coordinating Council (VICC), a “race-based transfer that allows Black city children to attend county schools.” This program is winding down, but its dissolution may be premature. With 94% of majority Black school districts in St. Louis, typically situated in impoverished areas of the city, being eligible for FRL, they should rationally receive greater overall funding per-pupil than nearby districts with lower FRL rates according to the Foundation Formula. The opposite trend, however, is closer to reality.

Forced out of their established, prosperous communities, Black families in St. Louis were displaced to areas deemed less profitable for real estate and commercial structures, inevitably leading to lesser property values. The assessed property value per-student for majority Black districts is half of that for majority white ones, and the former typically vote to raise their tax ceilings in order to better fund their schools. This, however, is still not enough to make up for the vast differences in local funding. For the majority Black school district of Jennings to pay a comparable amount of property taxes to Kirkwood, they would have to raise their tax rate from 5.3889% to 22%, or 9.1% of median household income. This is simply not feasible, and although state funding attempts to alleviate disparities in local funding, it cannot account for how significant these differences are.

Well-funded schools have more experienced teachers, smaller class sizes, newer facilities, more extracurricular activities and enough money to mitigate violent behavior. Poorer districts have systemic factors outside of education affecting their socioeconomic trajectory, and with inadequate public school funding, they are further disadvantaged by yet another governmental initiative. When property taxes are championed as a prominent determinant of funding, the racist history behind property allocation is upheld instead of dismantled. The Foundation Formula essentially ignores the lasting relevance of racism on where people live.

Hold harmless provisions are unnecessary

There are two hold harmless provisions for the Foundation Formula: districts with less than 350 students may receive the same per-pupil funding as they did in the 2005-2006 school year if it is higher, and those with over 350 students may receive the same state funding they did in the 2004-2005 or 2005-2006 school years if they are higher. These measures were only supposed to last for a few years, as their goal was to minimize dips in funding during the transitionary years of the new formula. They are still in place, however, and by using 2004 property value assessments, many districts who have become more property-wealthy in the past 20 years can raise their state-allocated funding.

In 2019, five out of eight districts in St. Louis County that otherwise would not qualify for any state funding received it, and 14 districts from the area got $39 million in excess due to hold harmless provisions. According to a report titled “Districts Hold Harmless Districts for Fiscal Year Basic Formula Payment” published by DESE, districts like Clayton, Craig R-III, Shell Knob 78 and Brentwood have benefited from hold harmless provisions for the past 17 years. These are also the four wealthiest districts in Missouri, with an average assessed property value per-student of around $609,306.

These districts do not need the extra funding, and with state revenue allocation for public education being fickle, the little resources the state does extend should not be going to the districts that need it the least. It is not these wealthy districts’ fault, however, that they are receiving extra funding or better benefit from a school funding system based on property taxes. They are not doing anything illegal by making use of the opportunities before them; they, just like any other district, want to optimize their students’ education, and greater funding is a proven way to accomplish that. The existence of such loopholes is the problem, and it is the government’s job to amend that — but they are simply choosing not to.

WADA’s focus on attendance as a measure of funding is outdated

The Foundation Formula takes into account attendance for funding and weighs it based on the prevalence of students using FRL, IEP or ELP in a district. This system, however, punishes districts with students unable to attend school regularly due to legitimate reasons and does not properly differentiate between districts with significantly different rates of weighted factors.

Average daily attendance (ADA) is the metric used by seven states, including Missouri, to calculate state revenue for public school education, and it is “perhaps the most inequitable methodology in practice” according to Allovue. ADA measures the average number of students present in class over the course of a school year unlike metrics used by the other 43 states, like average daily membership and seat counts, which measure enrollment numbers and the number of students present on some randomly chosen day(s), respectively. These two measures are considerably less sensitive to absenteeism than ADA, while ADA directly undercounts the typically highest-need portion of a district. Students unable to attend school are the same students who need the most assistance in getting to school, and this assistance naturally manifests in the funding allocations for the districts they attend.

Black students on average miss four more days of school per-year than white students, and 52.7% of these absences are unexcused. Reasons for unexcused absences typically include troubles with transportation, taking care of younger children, truancy and more. In-school suspensions can often result from prolonged unexcused absences, and Black students are 2.5 times more likely than white students to be absent because of them, further bringing them out of school. Besides the effects this trend has on district funding, it also results in lowered instruction time for minority students.

According to a report published by the Show-Me Institute, in Missouri, “low-income students, students with disabilities, and students with limited English proficiency don’t necessarily generate additional

revenue for their districts, in contrast to most weighted-student funding systems.” Higher attendance too uniformly correlates with greater property values, and thus property-wealthy districts are once again unfairly benefited by the state. The Center for American Progress conducted a study in Missouri and five other states where students living in higher-poverty districts had less access to school funding than those living in less poverty-prone areas, finding that Missouri only provides additional weighting for programs like FRL if their rates are above the state average. Essentially, all weighting is done independently from each other, meaning that a poorer district, for example, will not receive more funding per student needing IEP or ELP than a wealthier one, even though they would likely need more in order to successfully implement such facilities.

There is a general lack of nuance in how the Foundation Formula is structured, as it does not properly account for the reasons behind certain trends. By not recognizing that a funding system dependent upon attendance rates and obtuse understandings of FRL, IEP and ELP numbers directly hurts lower-income Black and brown students, the government is ignoring a problem of which they are the sole perpetrator. Ignoring the issue does not diminish its prevalence, it only makes it harder to identify and fight.

Equity has never been at the forefront of public education in Missouri

In 2004, the Committee for Educational Equality filed a lawsuit against the state, claiming that the new Foundation Formula underfunded public schools. Over 250 of Missouri’s 523 rural, suburban and urban school districts participated in the case, challenging both the adequacy and fairness of the newly instated formula. But, there is only one thing written in the Missouri state constitution about public school funding: at least 25% of funding must be extended by the state.

Citing this and the fact that “notably, no expressed right to equitable education funding exists” in the state constitution, and that there is also no explicit expression for “a free-standing right to ‘adequate’ funding,” the official case statement shut down any argument advocating for educational equity in funding on the basis of legal terminology. Using a strict constructionist framework, the court additionally preemptively denounced any future lawsuit attacking the Foundation Formula for the reason of equality.

The use of semantics by the supposedly bipartisan justice system to trivialize accusations of inequity fostered by government bodies is legal rigamarole, as it allows courts to ignore the moral and social context of a situation. Even measures that champion progress do not always result in change: Shelley v. Kraemer did not end discriminatory housing policies, the VICC did not fix segregation in schools and the new Foundation Formula did not rectify unfair school funding practices. The bureaucratic manner in which the Missouri government handles funding is, simply put, inadequate and regressive.

At this point, widespread change can only be made through lobbying and grassroots efforts. To bypass a lack of explicit wording in the state constitution, legislation would be an effective way to enforce reform and enable future legal challenges. Government officials and lawmakers in Missouri, however, too often fail to grasp that their policies do not exist in a vacuum: they either hurt or facilitate underlying systemic issues. When government bodies neglect their constituents, residents hold the unfair burden of rectifying issues their representatives are supposed to address. It is up to Missourians to independently recognize, evaluate and address the causes and effects of inequitable school funding. Grappling with aspects of a larger, systemic issue may seem insignificant, but each small step is necessary for dismantling overwhelming structures. When one looks at The Promenade, they must remember Howard-Evans Place and feel a sense of anger.

Have you ever heard of Howard-Evans place? Let us know in the comments below.