Sitting at my open front desk located near the middle of the classroom in third grade, I guided my pencil across my worksheet, tracing each letter of the alphabet in cursive. As I worked, I felt a repetitive thud against my ankle every couple of seconds. I ignored the nuisance at first, but when I finally turned around, I saw the boy behind me swinging his leg toward my foot and grinning down at his paper in a poor attempt to act as if he wasn’t aware of what he was doing.

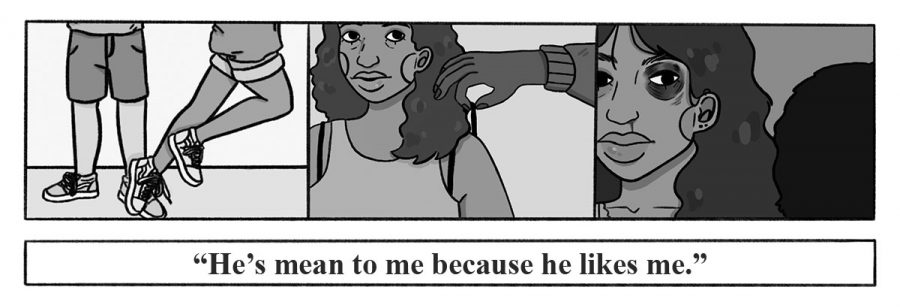

I told him to stop, then returned my attention to my cursive practice. In less than a minute, I felt his shoe hit me again. Frustrated, I let out a soft groan and walked up to my teacher’s desk where I told her what was going on. She looked up at the boy and back to me and said, “He’s probably just doing it because he likes you.” I was unsure whether I should feel flattered or irritated.

A similar incident occurred in fourth grade. I often played four square with my friends during recess and even though I wasn’t very good at this game, I still considered it one of my favorites. After a few rounds, I worked my way up to the first square; I was pretty proud of myself. Just after I served the ball, a boy who wasn’t involved in our game darted into my square and intercepted it.

He snatched the big green ball mid-air and ran with it clutched tightly in his hands around the gravel track, stirring up dust behind him, hoping he’d lose us. Three of my friends and I chased him and yelled at him to return it, but he outran us. Since we couldn’t solve the issue ourselves, we resorted to tattling. I told the playground supervisor about the mischievous boy, and he grumbled, “He’s just teasing; that probably means he likes you.”

I didn’t understand why teachers excused boys’ bad behavior as flirting while girls didn’t receive the same treatment and faced consequences for their actions. Throughout elementary school, I believed when boys pestered me it meant they had a crush on me. That mindset didn’t put me at risk of dating violence at a young age, but in middle and high school where flirting is more common those beliefs make me more susceptible to abusive, manipulative, or violent relationships than girls who were taught consent.

Boys being devious in elementary school took the form of a continual kick at my ankle and a disrupted game of four square, but as I grew older, these bad behaviors became more devious. I saw boys snapping bra straps of other students in middle school and making unwanted comments about girls’ bodies. An annoying thump on my ankle was nothing to go home and cry about, but allowing boys to get away with minor offenses in elementary school can lead to them dodging repercussions of bigger conflicts in the future. An article by empoweringparents.com reinforces that idea and said, “Many parents either don’t hold their kids accountable or don’t follow through on the consequences once they set them, which in turn just promotes more irresponsibility.”

When adults teach inaccurate definitions of flirting, they support harmful ideologies that could make girls vulnerable to dating violence or abuse — when one member of the relationship shows a pattern of controlling, abusive, and/or aggressive behaviors — in the future. Womankind Worldwide, is a global women’s rights organization working in solidarity with women’s movements around the world to bring about lasting change in women’s lives. They support the idea of replacing old beliefs that support violence with more progressive ideologies. An article on their website states, “Ultimately the key to ending violence against women and girls is in transforming traditional gender roles and power relations, changing the attitudes and beliefs which allow violence to continue.”

Instead of dismissing boys’ bad behavior, adults in positions of authority should hold misbehaving boys responsible for their actions and teach them respectful ways of getting attention from a crush, such as inviting them to join a game or offering assistance. Teens need training to identify and approach red flags of dating violence like verbal or physical abuse, controlling tendencies, threats and more.

Teaching and enforcing accountability and consent early on is crucial to combatting dating violence. In my high school health class, consent is only taught with sex, but, in reality, it’s applicable to any form of physical contact.

At family gatherings, it’s a common practice for relatives to greet one another with hugs or kisses. I personally love hugs now, but when I was younger, I was much less comfortable with the idea of hugging people I hardly knew. Older men and women with unfamiliar faces smiled down at me with their arms wide open, anticipating a hug. Intimidated, I stared at the floor to avoid eye contact and slowly drifted behind my parents to hide myself. Oftentimes there were a few family members I didn’t know as well, so I was reluctant to greet them. Rejecting their hugs felt rude, so I forced myself to comply.

I formerly believed refusing to show physical affection to someone was a rude gesture, even if I didn’t know the person well. I never voiced how I felt about forced family hugs because I thought of them as a responsibility; not something I wanted to do but I still had to. An adult saying no to affection is something I’ve never really seen before. It’s important for adults to be role models of consent by being conscious of their touches and treating “no” as an acceptable answer so kids understand affection is given, not owed.

Children must also acknowledge consent goes both ways. At a family reunion a few years ago, my aunt and uncle showed up with their children. I bent down and opened my arms to greet a few of my younger cousins, but they shied away and hid behind their parents. At first, it bothered me that they didn’t want to hug me, and I felt slightly hurt, but then I remembered the discomfort I felt earlier on with some of my older relatives. I understood how my cousins felt, we don’t visit them often so they probably weren’t too familiar with me.

Experiences like family gatherings and classroom conflicts are perfect opportunities for adults to enforce accountability and teach kids about consent.

In an attempt to prevent incidents with dating violence, unhealthy relationships and nonconsensual interactions, it’s a necessity for education on these topics to start at a young age. Saying “no” to unwanted affection and setting personal boundaries should be acceptable. Today’s youth need adults to emphasize respect, regardless of gender, and to be active examples of healthy relationships by displaying mutual consent and respect in romantic and platonic relationships alike. With comprehensive education about consent and healthy relationships starting as early as kindergarten, authority figures can begin addressing consent in the classroom so it’s applied in daily life down the line. One in three adolescents in the U.S. is a victim of physical, sexual, emotional or verbal abuse from a dating partner, according to Womankind Worldwide. The first step to prevention is education and accountability. I don’t want to add to the statistic.

Do you believe children should be educated on consent earlier? Let us know in the comments below.