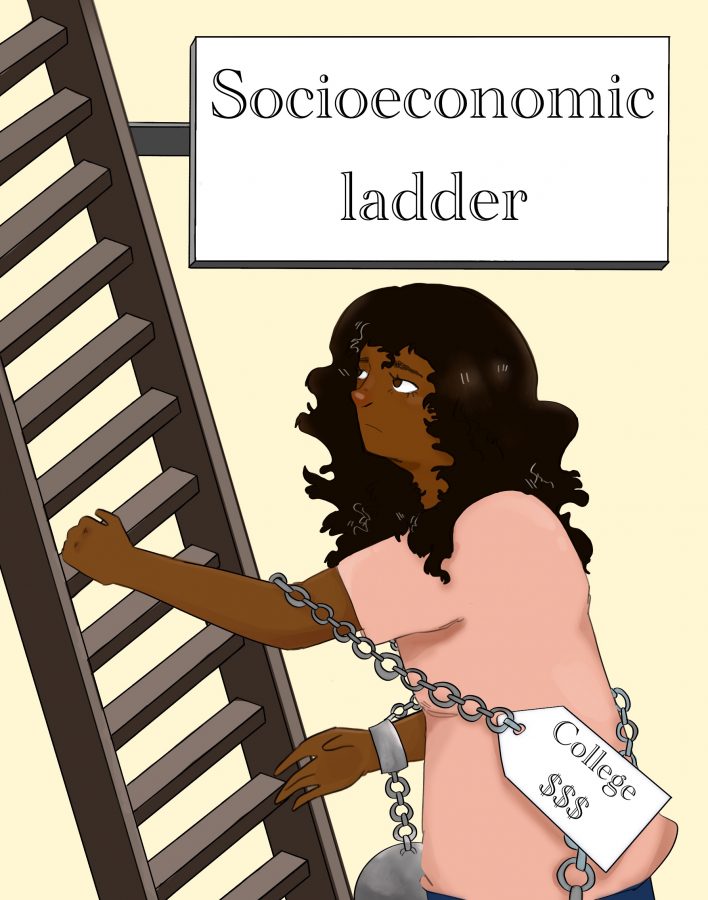

As a college degree has become more and more necessary to enter the workforce, universities have recognized the high demand and sent prices skyrocketing far faster than the rate of inflation. Student loan debt has ballooned in recent years, reaching $1.4 trillion in 2019 and becoming the second largest form of debt for American borrowers, behind mortgage debt. This crisis is particularly pronounced for black students, 87 percent of whom borrow federal loans compared with 60 percent of white students.

To truly provide equal opportunity to Americans as they enter adulthood, the U.S. federal government should provide scholarships to make college free for all low-income Americans, as defined by the federal government. This would serve to not only help eliminate the racial wealth gap but would also aid all low-income students in the struggle to pay for school.

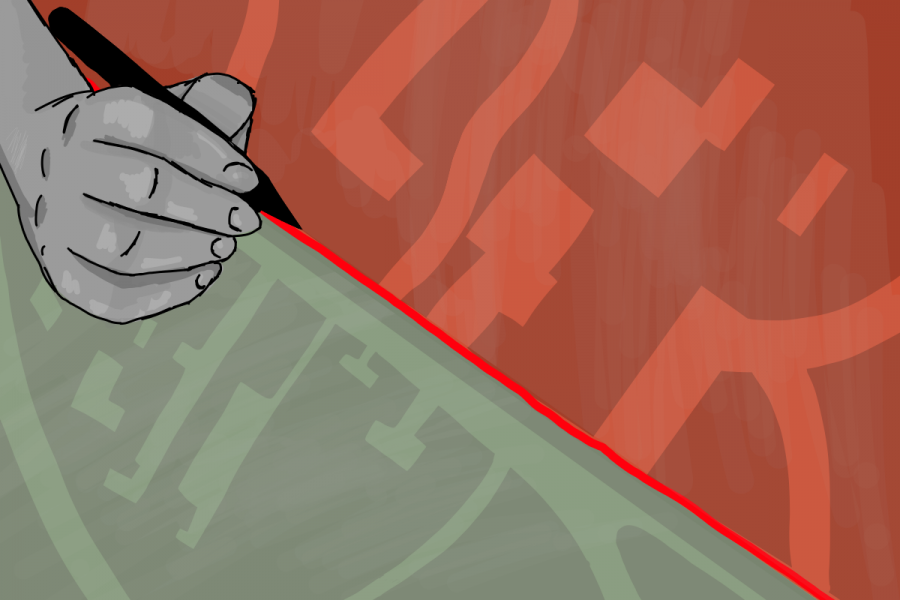

When it comes to tuition costs, price discrimination is holding down low-income Americans, preventing them from having any upward mobility. Kristin Wong, author of “Get Money: Live the Life You Want, Not Just the Life You Can Afford,” describes price discrimination as “the strategy of selling a product at a range of prices to maximize profits, and usually, that price is whatever the customer is willing to pay.”

A common example used for price discrimination is airplane tickets. Airlines create different price levels through first-class, business-class and economy-class tickets so they can attract customers at different incomes. Then, they fluctuate the price according to the date of the purchase in relation to the date of the flight to extract as much from a customer as they possibly can. For instance, if someone looks to buy a ticket for a flight in a couple months, the airline keeps the price at a more moderately-priced level so as to not scare away the potential customer. If someone looks to buy a ticket last-minute, however, the airline jacks up the price substantially because the buyer would be more desperate.

When this translates to colleges, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) that many colleges require is used to price discriminate as explained by Kevin Carey, director of the Education Policy program at New America. Although on the surface colleges’ use of financial aid to meet demonstrated need benefits low-income Americans, it brings an insidious problem.

“Colleges say [they want] to calculate the ‘best’ financial aid package for each student,” Carey writes. “They actually want to find the price that is best for the college, in the sense of charging the most parents can bear … But there’s a profound problem with price discrimination. Once you charge every customer exactly the most they’re willing to pay, there’s nowhere else to go.”

While need-based aid is better than nothing, the federal government should do more to enable low-income and minority students to combat the inequities they face and improve their socioeconomic standing. Price discrimination hits these two historically disadvantaged groups particularly hard, as colleges squeeze out every last dollar they can.

When it comes to public universities, a high price tags reduction in diversity is especially pronounced, as they often provide less need-based aid than private universities with large endowments. In fact, a study on the cost of college’s effect on student body demographics from The Conversation found as the sticker price of tuition at a public university goes up, diversity on campuses goes down.

“We examined tuition hikes at public four-year colleges and universities over a 14-year period,” the authors write. “What we found is that for every $1,000 increase in tuition at four-year nonselective public universities, diversity among full-time students decreased by 4.5 percent.”

This high cost of college presents a detrimental Catch-22 for minority applicants. Either they can forgo college to avoid incurring debt but miss out on the higher career earnings that come with a college degree, or they can go to college and get a degree but have the spectre of debt follow them for years afterward. Indeed, a study from the Center for American Progress, a public policy research nonprofit, found that African American students who get their bachelor’s degree still disproportionately struggle paying off loans.

“Twelve years after entering school, the typical African American borrower who completed a bachelor’s degree owed 114 percent of what they originally borrowed,” Ben Miller, author of the Center for American Progress study writes. “The corresponding figure for white students is 47 percent.”

The racial wealth gap in the U.S. is massive: for every $100 in white family wealth, black families hold just $5.04, according to an article from the New York Times. This a complex problem built from centuries of racism. Making college tuition free for low-income Americans is a necessary step to help chip away at the issue. Price discrimination and high tuition in public universities is putting a disproportionate weight of student loans on black and low-income borrowers, and current scholarship programs are not equipped to address this. By increasing aid to these groups, the U.S. federal government can help to ensure already disadvantaged Americans are not already placed under the substantial economic burden by debt when they enter adulthood.

What do you think should be done about student loan debt? Let us know in the comments below.

Nick Clervi • Feb 2, 2020 at 8:22 pm

This article skips the variable of financial education in high school. Successful, knowledgable students will only take out a loan if they have a plan to pay it off. Most students don’t understand that when you pay out the entire duration of the loan instead of paying to off early with result in you paying 15+% more. A smart loan has enough time for you to pay off the loan for exactly the price you took it out for, most do not understand this which is another reason they fall under the percentage mentioned in this article along with what you mentioned.