In seventh grade, I told one of my closest friends that I was starting to experience attraction to the same gender. This was an unbelievably important moment for me, as it was the first time I had told anyone that I was questioning my sexuality.

I had been feeling attraction to more than one gender for about a year and was finally ready to tell someone. I wasn’t afraid of rejection or a negative reaction because I deeply trusted this person, and I thought she would be understanding about this subject; she had previously told me she was attracted to girls, her same gender.

At first, she was just as understanding as I had hoped. She told me how what I told her didn’t change our friendship and how she was thankful that I trusted her enough to tell her. In the following weeks, however, she was incredibly abrasive and pressured me to say that I was gay. She asked questions meant to reinforce my attraction to men, like demanding of me which boys I thought were cute and why I didn’t like girls. She insisted I say I didn’t like girls and that I was actually only attracted to men. When I resisted and said I did still like girls, she called me a liar and said I was straight and playing a trick on her. She would roll her eyes and say, “Come on, I can see through your little act.”

I didn’t know how to respond, so I did my best to ignore her comments. At a time when I was just beginning to discover a large part of who I am, this experience was extremely troubling. It was hard enough accepting that I wasn’t straight, and these comments only added to the stress that exploring my sexuality inflicted. I felt like my friend was betraying me, using the fact that I was attracted to the same gender as a weapon to pressure me to make me make conclusions about myself when I wasn’t even sure exactly how I sexually identified.

Since then, I have made far more understanding friends. Coming out to my current friends was extremely casual because I am more comfortable than I previously was in my sexuality and because the friends that I have now accept my bisexuality. When I came out to them, they simply said, “Okay.” They did not probe or ask too-personal questions; they simply thanked me for trusting them and moved on with the conversation.

Though I am still going through this large, transformative moment of my life in which I am discovering my identity and get the hang of who I am attracted to, I have learned so much about myself. During the past four years, I have discovered that I like chocolate more than vanilla; I enjoy iced coffee more than hot. Flickering lights annoy me, and I am bisexual. I have identified as bisexual for a few years, but finding comfort in this label has come with its difficulties. While I feel it describes me, it is hard for people to understand this adjective if they are only attracted to one gender.

For as long as I have identified as bisexual, I have noticed small, offhand comments about me and/or my sexuality that made me raise an eyebrow from both my straight friends and LGBTQ friends. While some may have had good intentions by acknowledging the normality of my attraction to men or in an attempt to make a wisecrack, friends of mine have accidentally stepped on or ignored my sexuality. They made it seem as if I only liked guys or was lying about my attraction to girls. “Don’t worry, you’ll find a cute guy in college,” they’d say. “I’m sorry the boys in Columbia suck.” On countless occasions, my friends have jokingly called me gay or dismissed my behavior by citing a gay stereotype, like when I jested about how I was dying to bake Christmas cookies and one of my friends said, “God, you’re so gay.”

I almost always let these comments slide, or, when I don’t leave the matter alone, I gently remind them: “I like girls, too.” Because I know my friends mean no harm by these gags, I am not offended by gay jokes at my expense. Besides, I don’t enjoy shoving my sexuality in the faces of others and making a big deal of it. For example, when I want to correct someone, I don’t blow up at them in front of a big group. If the comment the person made is during a group dinner, I text the person individually afterward and gently bring his or her attention to what he or she did, how it was incorrect and politely ask him or her to be more mindful in the future.Apparently, I am not alone in experiencing these instances of bisexual erasure. “It’s just a phase” is a common phrase people often use to question the legitimacy of bisexuality, and it is an example of bisexual erasure, according to GLAAD, an American non-governmental media monitoring organization founded by LGBT people in the media.

Bisexual erasure is questioning the legitimacy, or even the existence, of bisexuality. Outside of my small scope of the world that includes just my friends and family, negativity both within and outside of the LGBTQ community further perpetuate and proliferate bisexual erasure. Bisexuals face many stereotypes from some gay and straight people, who say bisexuals are greedy, need to pick a side, think of nothing except their sexual desires and other judgmental comments. I have heard multiple stories of people in Columbia refusing to date a bisexual person because his or her attraction to multiple genders makes him or her “untrustworthy.” While I have never experienced this, I would feel destroyed if I had to face this discrimination coming from someone I had feelings for. People call bisexuals cowards: gay people in disguise who are still hiding halfway in the closet, too afraid to come all the way out.

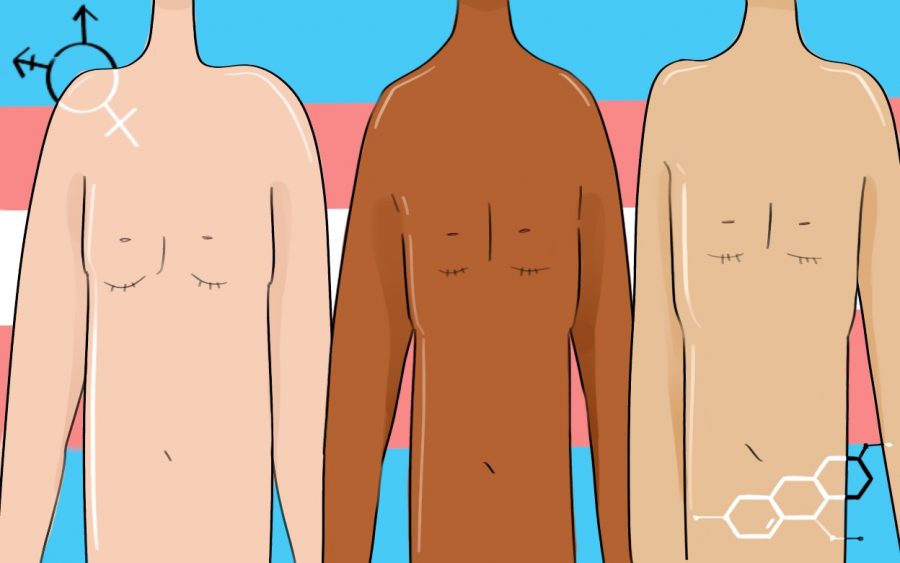

This pressure and discrimination can be extremely harmful to the mental health of a young person discovering his or her sexuality. Bisexual adults are far less likely to be out than gay or lesbian people are, according to the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan American think tank based in Washington, D.C. that provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the world. My fear of the intolerance I have faced could have shoved me deeper into the closet or made me to suppress part of my sexual identity, either my attraction to men or women, causing me to never truly find, explore and celebrate who I am naturally.The pride flag of bisexuality is trisected by segments of pink, blue and purple. Pink for the attraction to the same gender, blue for the attraction to other genders and purple for the intersection and synthesis of these attractions. Some individuals, like me, prefer a pinker shade of purple. Other’s purples may be darker and closer to blue. What is most important to remember, however, is that no matter how pink or blue a shade of purple is, it’s still purple. It’s still valid. Just because I tend to be attracted to the same gender more often than any other doesn’t mean I am not bisexual, and it doesn’t mean my bisexuality isn’t authentic. Coming out will never be an act of cowardice. Knowing the amount of courage it took for me to come out to my family and friends as bisexual, I can say that if I were gay, I would have had the guts to say it. No matter what sexuality you are, coming out will almost always be scary. Saying that bisexuals are homosexuals too scared to come out is simply untrue.

After learning more about and facing bisexual erasure, I am more emboldened than I was before to be myself. In the future, I believe my best course of action in fighting bisexual erasure is simply being who I truly am. By embracing my identity and fully leaning into all aspects of my sexuality, I can be a living example for myself and for other people that bisexuality is real and genuine.

Why do you think it’s important for people to use correct labels? Let us know in the comments below.