I remember a mock election in my Civics’ class freshman year where we voted for a Democratic and Republican president. I ran for the Democratic president slot. I came in second for the presidency and instead of taking the chief-of-staff position, I focused my energy on creating a print newsletter to help the Republican side of the classroom better understand the blue opinions.

I became the leader of a small group of other 15-year-olds that I don’t think cared as much as I did about the newsletter. Using what I learned from my introduction to journalistic writing class, I put the newsletter together with visual aids and small stories, and passed it out to my classroom, eagerly awaiting to see their reactions.

After sitting back down at my desk filled with adrenaline and excitement, I stared at a classroom of glossed-over eyes staring down at the page I worked so hard to craft.

In that exact moment, I knew my greatest challenge as an aspiring journalist would be convincing people to read and understand my work. The empathy that carried my values drove me to want to tell people’s stories to help broaden the understanding of any topic to the general population. I wanted to make people read stories to change their lives and their viewpoints, not necessarily to my own, but my goal was to open minds.

As far as I know, no one read my newsletter, and even if someone did, I doubt they internalized it enough to make my hard work worthwhile.

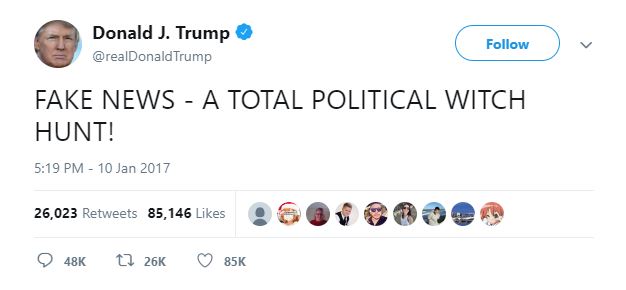

Now, three years later, I’m not even sure anyone will read this article, especially in an era of journalistic mistrust and “fake news.”

There are fabricated articles circulating the internet and viral videos that don’t show the whole story to an issue people get heated over. Fake news is real. Articles came out about the Covington Catholic “Make America Great Again” boys “verbally fighting” with an elderly Native American man and the internet got angry, but prematurely. News outlets such as CNN released the video before truly understanding the whole story in an effort to, once again, generalize Trump supporters. The New York Times jumped on the story so fast, they missed the fact that the Native American man was not a Vietnam War Veteran, making him an unreliable source. As long as news outlets report without doing proper research and background checks, “fake news” will continue to be a real and legitimate problem, and it will not be President Trump’s fault.

Yes, fake news is real, but it’s not just liberal media attacking Donald Trump. The Denver Guardian published a story entitled “FBI Agent Suspected In Hillary Email Leaks Found Dead In Apparent Murder-Suicide.” This story was completely false, yet people believed it as they shared it on Facebook over 500,000 times. Later, NPR tracked down the man behind many of these sites, Jestin Coler. Coler said in an interview with NPR his mission was to “highlight the extremism of the white nationalist alt-right.” People believe what they want to believe and will manipulate any “evidence” they can to support their opinions.

“The whole idea from the start was to build a site that could kind of infiltrate the echo chambers of the alt-right, publish blatantly or fictional stories and then be able to publicly denounce those stories and point out the fact that they were fiction,” Coler said in an interview with NPR’s Laura Sydell.

If fake news in an instance like this was to expose people who didn’t understand inaccurate versus real reporting, then what about when big-name sites like CNN and The New York Times practice inaccurate reporting? On the site Media Bias/Fact Check, NYT leaned left-center, with a high rating of factual reporting. Despite this rating, their coverage of the Covington Catholic catastrophe seemed to botch their reputation and their high rating. In that instance, their reporting experienced tunnel vision; reporters saw one angle of a story and decided not to look deeper into the situation. This resulted in a large loss of credibility for both NYT and journalism in general.

“Fake news” is a double-edged sword. On one end, all news outlets are not unanimously presenting factual, unbiased information while on the other, readers are crying wolf over articles they simply dislike. Because not all sites are legitimate, journalists’ reputation in general suffers. As the old saying goes, “one bad apple spoils the bunch.” Journalistic mistrust is not something that can be fixed simply by both parties being aware of how they are giving and receiving news and changing their ways. Instead, readers should fact-check what they read before spreading the news. If something is debunked before is sparks outrage, fewer people’s reputations will be ruined, as seen with the Covington Catholic story. Three easily accessible fact-checking websites include Media Bias/Fact Check, Politifact and Snopes. By fact-checking our news outlets, we as readers can prevent from validating and spreading harmful misinformation. These fact-checking sites are not the only way for readers to find credible information and resources.

After analyzing several headlines of the NYT, I found that their stories, especially regarding politics, are something readers will have to investigate the credibility of before reading and believing the reporting. If readers would click on the linked sources of information, read about the freelance writer’s past and credibility, and fact-check their own knowledge by reading about the same subject on other sites, then the world would be in a better place when it came to ignorance and quick-jab attacks. The problem is, despite my greatest hopes, I do not see a bright future for journalistic integrity.

In a perfect world, all news sites would follow their mission statements without faltering.

With continuous suspicion into the ethics of the above sites’ reporting, the general public has reason to be cautious of the articles they read online. It should not be the reader’s responsibility to investigate each article he or she reads. The news sites themselves should never present misinformation. The relationship between journalism and the public is delicate. During the American Revolution, journalism allowed the public to express concern about English policies. In 1776, Thomas Paine published Common Sense, where he advocated independence for the colonies and united colonists against the British. The original purpose of journalism was to present information. The citizens make the news and it is a journalist’s ethical responsibility to report this information back to the public with truth and dignity. Even with this relationship, however, there are still variables that will establish mistrust including a poor journalistic history.

Articles being attacked with the label “fake news” is no new problem. In 1935, The New York Sun published a science fiction article about man-bats inhabiting the moon. Of course, people took the article seriously and began copying the story, making the hoax national news. While in this instance the article was not pretending to be real news, the satirical nature fooled the general public into believing and spreading misinformation, just as Coler did with the Denver Guardian. Predating the moon hoax, in 1769, John Adams crafted exaggerated stories meant to undermine royal authority. In his diary, Adams wrote, “The evening [was] spent in preparing for the Next Days Newspaper. A curious employment. Cooking up Paragraphs, Articles, Occurrences etc. — working the political Engine!” Later, in 1798, Congress passed Adams’ Alien and Sedition Acts. The Sedition act in particular was to prohibit public opposition to the government. Anyone who dared “write, print, utter, or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing” was subject to fines or even imprisonment. When Adams’ presidency expired, as did the Sedition act.

Well, yes, but no.

Journalists do not — or should not — have the authority to publish anything that crosses their mind unless the article is obviously titled as an opinion piece. Even with the ability to publish their opinions, some reporters still insert bias into non-opinion pieces or publish stories without making sure every detail is edited and accurate. Even when a reporter has a just hint of bias, they are less likely to be treated with respect.

President Trump temporarily revoked a CNN reporter Jim Acosta’s press pass in November 2018 and later said he may do the same to other reporters. The suspension of Acosta’s pass rose after a verbal quarrel between Acosta and the president after Acosta challenged Trump’s campaign ads and accusation of a migrant caravan moving through Mexico as an “invasion.” Acosta continued to accuse Trump of demonizing migrants. Throughout the encounter, the two continue to interrupt each other and President Trump eventually tells Acosta, “that’s enough” as a White House intern moves to revoke the microphone from Acosta, who refuses to give up. In the video, Acosta brushes the intern off, saying “pardon me, ma’am.” Trump later calls Acosta “a rude, terrible person” and said, “CNN should be ashamed of itself having you working for them.”

After the interaction, White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders released a statement, saying,

“President Trump believes in a free press and expects and welcomes tough questions of him and his Administration. We will, however, never tolerate a reporter placing his hands on a young woman just trying to do her job as a White House intern. This conduct is absolutely unacceptable. It is also completely disrespectful to the reporter’s colleagues not to allow them an opportunity to ask a question. … As a result of today’s incident, the White House is suspending the hard pass of the reporter involved until further notice.”

Later, The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, an nonprofit organization that provides free legal assistance to journalists released a counter-statement:

“The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, the nation’s premier defender of the legal rights of journalists, joins the White House Correspondents’ Association in vehemently objecting to the revocation of a CNN reporter’s access credentials. Journalists have a right to ask questions and seek answers on behalf of the American people.”

When the figurehead of a country publicly announces his or her dislike for something, he/she’s followers will do just the same; they will follow. The Journal of Social and Political Psychology might have found a few reasons why President Trump seems to gather such a unique and loyal following: authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, prejudice, relative deprivation and intergroup contact. Psychology Today further explains these traits. Authoritarianism follows the idea that the leader lacks concern for the opinions or needs of others. People who practice authoritarianism often have belief in one’s total authority, and often display acts of aggression toward members outside of their target group. With President Trump, this idea is most commonly associated with his speeches with the usage of terms like “complete and total disaster,” “He’s a sleeping son of a b—.”

No matter the context, Trump’s harsh vocabulary displays dominance and appeals to his followers.

This analyzation of President Trump’s leadership style explains why his followers are so loyal, and why they seem to resent journalists because of Trump’s attitude and actions toward them.Again, Trump’s presidency shows that the general population follows its leaders. People seem to gravitate toward anything — or anyone — that seems to align with their political values.

Even as all the chaos of politics and scandals swirl around me, I still remember my roots and why I started writing. I wanted to tell people’s stories, to open minds and to give a new perspective on different topics. I continued to write despite the president’s feelings about journalists, but I couldn’t help but feel dragged down by his words, even from thousands of miles away.

Today’s journalistic climate is infiltrating people’s minds like an infection. Trump seems to have coined the phrase “fake news,” though he did not invent the saying. I know each time someone says the phrase where he or she is getting it from.

In October, as two of my friends and fellow staff members walked along the pavement of a homecoming football game downtown attempting to fundraise for our paper and among dozens of interactions, one stood out in my mind. We approached a group of people sitting in lawn chairs outside of a recreational vehicle, drinking beers and watching the football game on the television.

I gave my pitch about how my newspaper class is raising money to go to a journalistic convention, and as sympathetic adults handed us one dollar bills one man said to us in an accusatory tone:

“You aren’t fake news, are you?”

I felt a sudden sting. This man didn’t know us or what we wrote about, yet he was immediately skeptical of our ethics and integrity. Instead of showing my sensitivity, I simply forced out a laugh and said:

“No, sir.”

I recently committed to the University of Missouri—Columbia to study journalism. I couldn’t help but question if encounters like the one with the man were my future. I pictured a life of constantly having to prove myself reputable because a few bad apples and a very opinionated president soiled the view of journalism. I wasn’t ignorant to fabricated stories and misinformation. I knew that some journalistic sites are biased and some follow payola journalism, where advertisers pay writers to report on certain subjects.

Even before I began my long trek to become a professional journalist, I was already getting knocked down by a general mistrust of the media.

My defining moment as an aspiring journalist did not come from a middle-aged white guy making crude remarks without realizing it: instead, the most dream-crushing moment came from a video that emerged of President Trump being rude to a journalist—again.

The video came from a press conference that took place to discuss a new trade deal.

Trump, after calling on ABC reporter Cecilia Vega: “She’s shocked that I picked her. She’s, like, in a state of shock.”

Vega: “I’m not, Thank you, Mr. President.”

Trump, mishearing “thank you” as “thinking,”: “I know you’re not thinking. You never do.”

Vega: “I’m sorry?”

Trump: “No, go ahead. Go ahead.”

During this exchange, several men stood behind President Trump smiling or even laughing, at the banter before them.

Imagine growing up wanting to be an astronaut, then standing by as the public ridiculed the astronaut for doing their job just because the ridiculer didn’t like astronauts. Imagine what that would do to someone’s aspirations. Now imagine it happens every day, and the ridiculer is someone who has a platform to reach everyone and the power to create a stigma against astronauts.

The problem isn’t just a battle between President Trump and journalists, either. Opinionated students base opinions around the headlines of articles before reading the whole story, leading to misunderstandings and the spread of misinformation. The problem of “fake news” isn’t just in the articles written online, but also in the way the population is consuming information.

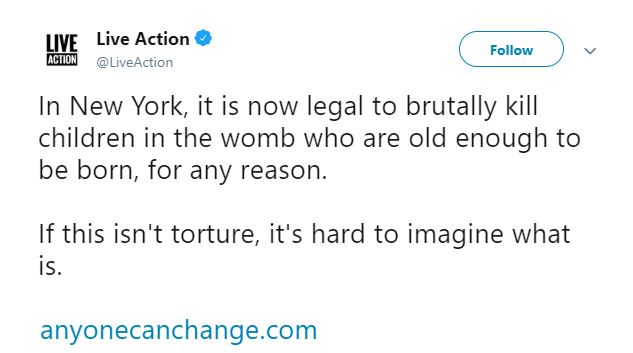

On social media site Twitter, I came across a reaction to a recent bill passed in New York. The Reproductive Health Act was signed into law by Governor Andrew Cuomo Jan. 29 to replace a 1970 state abortion law, which occurred three years before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide. Previously, women were only able to have abortions after 24 weeks if the mother’s life was at risk. Now, women are able to have abortions if the fetus endangers their lives or if the baby is not viable. Additionally, the law moves the section of state law dealing with abortion from penal code to health statutes, and also allows physician assistants to perform some abortions.

On Twitter, the law was vastly reworded. In a tweet from @LiveAction:

“In New York, it is now legal to brutally kill children in the womb who are old enough to be born, for any reason. If this isn’t torture, it’s hard to imagine what is.”

Simply adding single words to convey a dark tone convinced the more than 10,000 plus people who retweeted this as well as the 16,000 plus people who “liked” the tweet that the law was sinister. “Any reason,” is simply not true. Spreading this information to impressionable people on Twitter is contributing to the era of mistrust and is allowing people to form radical opinions without being fully educated. People should encourage having differing viewpoints, but not when they base their opinions on fiction.

Simply adding single words to convey a dark tone convinced the more than 10,000 plus people who retweeted this as well as the 16,000 plus people who “liked” the tweet that the law was sinister. “Any reason,” is simply not true. Spreading this information to impressionable people on Twitter is contributing to the era of mistrust and is allowing people to form radical opinions without being fully educated. People should encourage having differing viewpoints, but not when they base their opinions on fiction. “Fake news” isn’t just an article written prematurely about something without the full picture. It isn’t just President Trump disliking when media outlets publish articles opposing his administration. Sometimes, “fake news” comes in the form of retweeting or spreading something without finding the source of what’s actually happening. These everyday scenarios prevent young journalists from developing confidently. If students don’t learn with strength, then the insecurity will manifest itself in their work, making it weak and more prone to error. When giving the public information — as with journalism — there is no room for error.

When I see someone doing what I hope to make a career out of only to get shut down and told they “never think,” and for that exchange to be broadcasted all over the country, I feel as if I am part of a hated minority. People follow their leaders, and the leader needs to set an example that’s not alienating a group that has a constitutional right — and need — to exist. Yes, there are articles and sites that project blatant bias and they are part of the reason there is such a problem with partisanship in the United States, but there are other sites that are reliable and deemed as “fake news” just because someone doesn’t like what they have to say. When I set out on my journey to change lives and open minds using journalism, I was excited to make a difference in the world, no matter how small. Now, I realize I can’t yet accomplish my goal until people first open their mind to journalism itself.

Brandon Kim • Mar 18, 2019 at 6:08 pm

This is a great article that is so true. Journalism is essential to American democracy and it’s important to our daily life.

Maddie • Feb 25, 2019 at 3:03 pm

This is a stunning article about the difficulties of “fake news” and pursuing a career in journalism. It does a great job of providing insight on the topic and the true importance of real, honest journalism!