[dropcap style=”flat”]G[/dropcap]rowing up with a mother who never got the chance to learn piano outside of basic lessons in high school, my sisters and I were showered with musical opportunities. In a way, she let us live the life she always wanted.

I grew up with etudes accompanying my baby babble. My sisters’ practice piano books became coloring books the moment I learned to hold a crayon. Lullabies were tracks off a Suzuki Violin School CD.

While I can recall the day my mother enrolled me in violin lessons, the beginning of my history with piano is more blurry; in fact, I doubt my mother even asked if I wanted to begin lessons. But since the age of five, I’ve spent almost every Friday playing on a Baldwin grand piano and listening to the instruction of my teacher, Mabel Kinder.

With two older sisters already in piano lessons, I had a reputation to maintain. My oldest sister was a model student who practiced every day for more than what was expected and understood what and how to practice.

It was during her performance for the Missouri Symphony Society’s get-together that she caught the attention of Bill Clark, a columnist for The Missourian. A few months later, an article appeared in The Missourian and the phrase, “The Three Yus,” appeared for the first time.

At the time I was only seven years old and had two years of instruction under my belt. Nonetheless, with the flurry of attention from all the other piano moms, teachers and family friends, I kept hearing how musically talented the three Yu daughters were.

But then as the years slipped by and I continued to perform, some people began to say, “Oh, the three Yus? They’re just talented. They were born with it.” Understandably, I liked when people said I was talented. After all, who doesn’t like to hear that they’re good at something? But this new addition “just” made me feel sick inside.

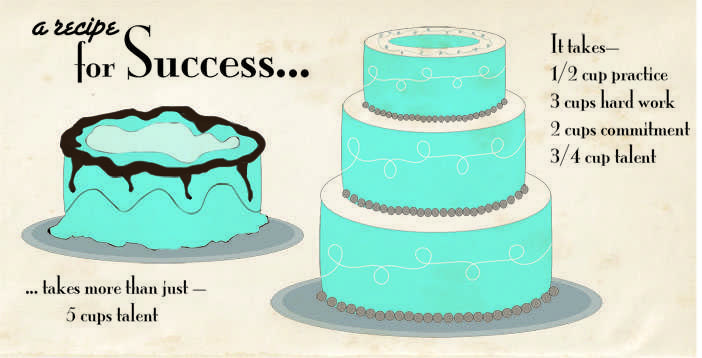

I might have been born with some talent in understanding and performing music, but it wasn’t the only thing to get me where I am now. Talent can only get someone so far.

As Daniel Coyle mentioned in his book, “The Talent Code”, world-class talent is developed and cultivated, not just dropped into someone’s lap. Oftentimes, growing this talent involves deep practice and long-term commitment. Deep practice itself calls for hard work, mountains of mental struggle and acute attention to fine details.

Saying that I’m just talented attributes the achievements I made after practicing multiple days for three hours straight to the idea that I just magically “got it.” Success does not come from talent. It comes from time, pain, sweat, frustration, tears and sometimes even blood. I have played until my fingers bled. Nothing out of a horror movie, but my liquid life force leaked out for the sake of expressing my musical soul.

Just like how a basketball player’s height and daily practice routine can contribute to a high success rate of free throws making it into the basket, talent and practice work together to bring a pleasurable performance.

To say a basketball player only makes his free throws because of his height and ignoring the days he spends perfecting his shot from the charity stripe is insulting.

To say people perform well because they’re genetically predisposed to do so and ignoring the hours they’ve spent practicing technique and refining the sound of each and every note is insulting.

Before attributing the success of an individual to her genetics, something she has no control over, realize that more often than not, there are hours of practice and preparation supporting her. To package all that time and effort into thin strands of DNA and call it someone’s sole source of success is hurtful and deprives the performer or athlete the credit they are due.

I don’t perform well because I’m just talented. Swimmers don’t reach the finish line first because they were just born with speed. Administrators didn’t get in positions they’re in now because leadership runs in their blood. For many who succeeded in their fields, their journey included sacrificing fun for grueling workouts and working overtime. The power behind recognizing someone’s conscious effort to improve and grow is truly the ultimate compliment.

How have you coped with others’ misconceptions of your passions? Leave your comments below.

I grew up with etudes accompanying my baby babble. My sisters’ practice piano books became coloring books the moment I learned to hold a crayon. Lullabies were tracks off a Suzuki Violin School CD.

While I can recall the day my mother enrolled me in violin lessons, the beginning of my history with piano is more blurry; in fact, I doubt my mother even asked if I wanted to begin lessons. But since the age of five, I’ve spent almost every Friday playing on a Baldwin grand piano and listening to the instruction of my teacher, Mabel Kinder.

With two older sisters already in piano lessons, I had a reputation to maintain. My oldest sister was a model student who practiced every day for more than what was expected and understood what and how to practice.

It was during her performance for the Missouri Symphony Society’s get-together that she caught the attention of Bill Clark, a columnist for The Missourian. A few months later, an article appeared in The Missourian and the phrase, “The Three Yus,” appeared for the first time.

At the time I was only seven years old and had two years of instruction under my belt. Nonetheless, with the flurry of attention from all the other piano moms, teachers and family friends, I kept hearing how musically talented the three Yu daughters were.

But then as the years slipped by and I continued to perform, some people began to say, “Oh, the three Yus? They’re just talented. They were born with it.” Understandably, I liked when people said I was talented. After all, who doesn’t like to hear that they’re good at something? But this new addition “just” made me feel sick inside.

I might have been born with some talent in understanding and performing music, but it wasn’t the only thing to get me where I am now. Talent can only get someone so far.

As Daniel Coyle mentioned in his book, “The Talent Code”, world-class talent is developed and cultivated, not just dropped into someone’s lap. Oftentimes, growing this talent involves deep practice and long-term commitment. Deep practice itself calls for hard work, mountains of mental struggle and acute attention to fine details.

Saying that I’m just talented attributes the achievements I made after practicing multiple days for three hours straight to the idea that I just magically “got it.” Success does not come from talent. It comes from time, pain, sweat, frustration, tears and sometimes even blood. I have played until my fingers bled. Nothing out of a horror movie, but my liquid life force leaked out for the sake of expressing my musical soul.

Just like how a basketball player’s height and daily practice routine can contribute to a high success rate of free throws making it into the basket, talent and practice work together to bring a pleasurable performance.

To say a basketball player only makes his free throws because of his height and ignoring the days he spends perfecting his shot from the charity stripe is insulting.

To say people perform well because they’re genetically predisposed to do so and ignoring the hours they’ve spent practicing technique and refining the sound of each and every note is insulting.

Before attributing the success of an individual to her genetics, something she has no control over, realize that more often than not, there are hours of practice and preparation supporting her. To package all that time and effort into thin strands of DNA and call it someone’s sole source of success is hurtful and deprives the performer or athlete the credit they are due.

I don’t perform well because I’m just talented. Swimmers don’t reach the finish line first because they were just born with speed. Administrators didn’t get in positions they’re in now because leadership runs in their blood. For many who succeeded in their fields, their journey included sacrificing fun for grueling workouts and working overtime. The power behind recognizing someone’s conscious effort to improve and grow is truly the ultimate compliment.

How have you coped with others’ misconceptions of your passions? Leave your comments below.