In an ordinary corner of RBHS, past the expansive art hallway and just before the journalism rooms, some of the school’s most extraordinary learning happens.

This cluster of rooms is home to 17 of the school’s teachers and around ten percent of students. These 180 or so students make up the special education department.

Nationally, students ages three to 21 served in federally supported programs for disabled students in public schools rose from 8.3 percent in the 1976-1977 school year to 13.2 in the 2008-2009 school year, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Educational Statistics.

At RBHS, a small, yellow circle in Home Access accompanies the names of these students to indicate that they have some sort of learning disability.

“The purpose of that yellow symbol, which really translates to an [Individualized Education Plan] document, is not to give that student at an advantage. It’s to level the playing field,” said Pamela Slansky, department chair of special education. “Students who have disabilities will probably have challenges their entire life. So they need to learn ways to compensate for those areas of deficit.”

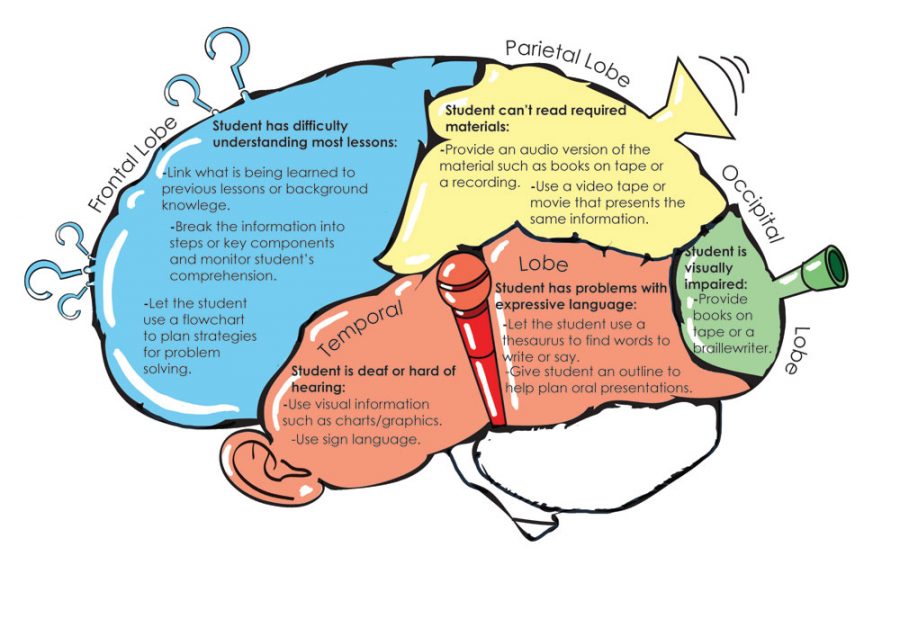

IEP documentation is different for each student depending on his or her disability area. For a student with a reading disability, the IEP may allow the student to receive audio books, to have tests read aloud or to take exams in a quiet setting, Slansky explained.

A student with a disability in written expression, however, might dictate test answers to a scribe to write down, or give verbal answers directly to the teacher or use programs like Dragon NaturallySpeaking. The best teachers learn to work with these students, Slansky said, and RBHS is full of these kinds of teachers.

“That’s part of what good teachers do, in terms of differentiating instruction They learn the different students’ learning styles. If they need to use a modality to substitute for an area of disability, that’s what should be done,” Slansky said. “That’s the neat part about Rock Bridge: our teachers are masters at that, at individualizing and differentiating.”

For junior Jay Whang, this personalization has been crucial to his education. He describes himself as a visual thinker, one who likes to respond to questions in an email rather than orally. Whang would prefer to work a problem on a piece of paper or a dry-erase board while other students assemble answers in their heads.

“Many teachers know I have Asperger’s, and they help,” Whang said. “For example, in biology, Mrs. [April] Sulze gave me a paper of questions [to] write the answers down while other kids listen.”

Whang said he has a few specific and temporary interests, such as “anime and Kurt Vonnegut” one week, and then “Jack Kerouac and literary techniques the next.” This makes it hard for Whang to focus on anything that doesn’t interest him at that point, he said. This is part of the reason he opted out of Advanced Placement World History class his sophomore year, where he felt the class was “force-feeding” him material he wasn’t interested in. He also has a short attention span, which he said can be detrimental if he loses focus during verbal directions.

“I remember at band when there was some kind of special announcement,” Whang said. “I kind of missed that announcement because I wasn’t paying attention. So I was thinking, ‘Why not just write it on the whiteboard?’”

According to the NCES, nearly six in every 10 students with a disability spent less than 21 percent of their school time outside of general class in 2009. Slansky said the learning specialists at RBHS “are in direct contact with the general ed teachers” to make sure time spent in general classes is beneficial and effective for students with disabilities. The special education teachers at RBHS communicate often with general education teachers to alleviate situations like Whang’s, Slansky said.

Each learning specialist doubles as a case manager for 15 to 16 kids, special education teacher Punam Sethi said. Sethi also uses her chemistry and biology backgrounds to teach separate, smaller biology classes for students who would succeed better with more individualized, specialized teaching.

“Our goal is to slowly, slowly to push them in the regular streamline,” Sethi said. “We don’t want them to be a failure in the education setting. I have students we have enrolled in the [on-level] Biology class. And sometimes, it’s a large class, sometimes it’s the labwork, the writing [that causes them to] shut down.”

Sethi said in these cases, the case manager, regular class teacher, principal and parents discuss if the student would have better success in Sethi’s self-contained Biology class, where she teaches 10 students at time, rather than the typical 25 to 30.

Another support system is the resource room, which is for IEP students enrolled in general, rather than self-contained, classes. The resource room has two learning specialists every hour, Slansky said, to help students with homework, reading and other necessities. Whang said he spent entire class periods in the resource room last year.

“It helps me to do homework,” Whang said. “It’s good that I have my own private bubble.”

All these strategies to support students with IEPs are to prepare these students for a time when they will have none of this help when the IEP will not be available.

“It’s no longer a right of the student to have all these accommodations at the university level,” Slansky said. “Our students are used to having lots and lots of accommodations or supports. They have been, through elementary, middle school, junior high school, given a lot of accommodations to help them succeed. And what we know is that at the college level or the university level, the supports look very different.”

Preparing students for a world without structured support of an IEP is one case managers focus on. They “need to help to tailor the student,” Slansky said, so that he or she will be ready for their post-secondary futures.

“Our students, they’re just amazing. And it’s wonderful for me to see a student who comes in as a scared sophomore and whose parents are nervous about their success because they have this disability; by the time they’re a senior, they have blossomed. They know who they are and where they’re going and they have a plan for their life,” Slansky said. “They’re successful, and when the walk across the stage, I think we just all feel just proud. And that’s very fulfilling to me.”

By Nomin-Erdene Jagdagdorj