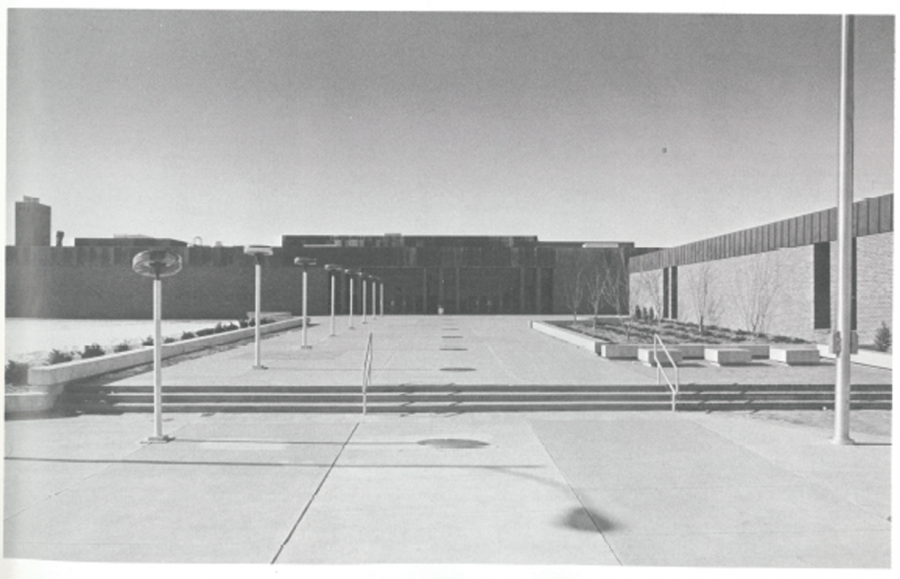

[TS-VCSC-Image-Switch image_start=”274158″ attribute_alt_start=”false” attribute_alt_end=”false” image_responsive=”true” image_width_percent=”100″ image_width=”300″ image_height=”height: 100%;” image_position=”ts-imagefloat-center” switch_type=”ts-imageswitch-fade” switch_trigger_flip=”ts-trigger-click” switch_trigger_fade=”ts-trigger-hover” switch_handle_center=”true” switch_handle_show=”false” switch_handle_color=”#0094ff” switch_click=”false” overlay_remove=”false” soverlay_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_css=”false” margin_top=”0″ margin_bottom=”0″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][dropcap style=”flat” size=”5″ class=”A”]1[/dropcap]973: Rock Bridge High School opens its doors for the first time. DUTs, or Daily Unassigned Times, and the whole idea of “Freedom with Responsibility” make this school unique from those around it. At the same time, President Richard Nixon ends U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War just as the Watergate Scandal breaks, which eventually leads to his resignation in 1974.

1992: The PAC, or the Performing Arts Center, and three new science classrooms are added to the school. A year before, the Soviet Union collapsed and in the Middle East, the Persian Gulf War ended.

1994: School bell schedule changes from a 50-minute, seven classes a day schedule to a 95-minute, four blocks per day every other day schedule. DUTs, or Daily Unassigned Times, change to AUTs, or Alternating Unassigned Times. Nixon passes away after suffering a stroke.

2000: Sophomore advisory is introduced for the first time and seven Science classes, seven Foreign Language classes, eight English and Social Studies classes, the media center and three new computer labs are added to the school. George W. Bush defeats Al Gore in the presidential election.

2013: School start times change to a three-tiered system, making high schools start an hour later. Freshmen join the high schools and eighth-graders join the middle schools. A daily Bruin Block schedule is introduced for the incoming freshmen and sophomore classes. A new gym is added along with a new wrestling room and a new weight room. The old wrestling room’s space is turned into four math classrooms and the old weight room is turned into a dance studio for the Bruin Girls. This same year, the Boston Marathon bombing happens, killing five, including an eight-year-old boy, and injuring 280 others.

2014: A new buzz-in system is introduced to all CPS schools. ISIS emerges in Iraq, splitting the nation in two and spreading massive fear throughout the population. It is no surprise that after 42 years, the school, and the world in general, has changed. The culture of this school from its start has been focused around change, according to Matt Webel, a Social Studies teacher here who also attended high school from 1993-96 in this very building. However, with time, everything eventually changes, because as time naturally progresses, so does everything along with it.

Webel’s “big change” was block scheduling. He experienced the same school that exists today; he attended a school that yearned for change, a school that would rather fail after trying than not try at all.

“Bruin Block [is] sort of the current attempt [here] to implement something that is good for kids. We are two years into it now, and I think that we have seen challenges to the system and some anger from students that don’t like it and some frustration from teachers who don’t like it,” Webel said. “And then on the other side you also see kids that say that it is a great experience that they have had and teachers that have said the same thing, so I think the hallmark of [this school] is that we listen to all of these concerns and opinions from all of the constituents, and then we make a good decision moving forward.”

Three years ago, Webel moved to Boston after teaching at this school for almost a decade. This school year, he returned to teach here again. Even before that, Webel attended high school here from 10th to 12th grade in the mid-90s and was a student when the bell schedule changed in 1994.

“I was a sophomore becoming a junior, so I don’t remember anyone asking me what I thought or soliciting my opinion or student opinions, which doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. I just don’t remember it,” Webel said. “I think initially I was put off by the amount of time that I had to spend in one place and back then, I think it was still a very stand and deliver model of education, so it was a lot of sitting in desks and listening to teachers, so over the course of time I think we have had to figure out ways to adapt our teaching to take into account the fact that these are longer classes.”

Eventually, after a few months of this change, Webel said he began to like the new model mainly because of two teachers who made it seem fun for him a student. In his sophomore year, Webel had Bill Priest as his World History. When the schedule change happened, the school also joined together all English and social science classes into block classes with two teachers.

“Junior year, I had Mr. Priest and [Michael] Bancroft for the first ever combined, interdisciplinary course of U.S. studies, and I just remember it was the first time that I had ever seen two teachers in the same classroom and the dynamic relationship that the two of them had, not only with each other, but they were able to have with us as students I thought created a much richer classroom environment, especially since I had Mr. Priest a year before,” Webel said. “You could tell they had a good relationship with each other. They appreciated each other’s intelligence and perspective … and we would see them interact and even laugh with each other about stuff that was happening in class and I could tell that they enjoyed what they were doing. From that moment on, I think really early on, and it was a lot because of the dynamic personalities of both of these teachers and how they related to each other, but I was sold on the model, and I have believed in it ever since.”

Webel said the way the school changed during his time as a student is similar to the way the school is changing currently with, for example, Bruin Block or the later school start times.

“I think, like anything at RBHS, we don’t exactly know how [the change] is going to go. We believe in [the change] in theory, or we like it in theory, or there are certain things that we want to adapt to our system, so I think block scheduling is like that, and I think integrated curriculum is like that and Bruin Block fits in that same category,” Webel said. “[These are] things that we think are going to be great for kids and great for our school and building a culture. We see a problem or a need, and we try to address it. So I think all of the changes that we are talking about have been implemented with good intentions, but I also think at RBHS we have the humility to look back and say ‘well maybe that decision didn’t work out the best way,’ or maybe ‘we had good intentions, but we couldn’t figure out a way to implement it.’”

With all of these changes, Webel believes the overarching DNA of the school will always stay the same. As long as this element is in place here, this school will continue to be the unique school that it has always been.

“Freedom with responsibility was still the motto we talked about all the time. We still got flogged from the community for allowing kids to leave campus for lunch, so those were the principles that were there,” Webel said. “But I think over time, we have developed them more and figured out ways to talk about them and express them to the community. Because in the beginning it was like we just do it and there was no real reason … but over time, we are able to see the benefits, as 25 years of kids, or however old the school is, have gone through the system and have been able to come back and talk to us about how [it] prepared [them] for college.”

Part of the reason why the DNA of the school is still unchanged is because of the many generations of students who have walked in these halls. Fellows Mentor David Graham, who helps and mentors masters students from the University of Missouri who work here, believes that the vast majority of the student body of this school today is similar to the vast majority of the student body when he went to this school 29 years ago in terms of academics. However, he has noticed a change in regard to the involvement of students.

“More students went to more athletic events and dances and things like that [when I went to school here],” he said. “I don’t know what the cause for that is, the disconnect. It is somewhat of a change, not a huge change, but there are a smaller percentage of the students going to the games than when I was in school, and plays and choir concerts and all of the extracurricular stuff.”

The changes RBHS has experienced in the past couple years worry Graham. He believes most students will do the right thing if given the choice between good and bad.

“The vast majority of our students are going to be just fine handling freedom with responsibility, but it is the extremists that make things tough for the masses,” Graham said. “I think that to people who went to traditional high schools, it is uncomfortable to see a school like ours that really does believe that kids would do the right thing first, and if you look at the vast majority of the building since the time it opened in 1973, they have done just fine all the way through to today.”

However, Graham thinks adding things like locked doors and cards to get people in and out of the building, while necessary, is a small step in the wrong direction.

“It wasn’t done because this building decided it. The district decided that, and the district decided that for insurance purposes,” Graham said. “We have to do that, and I understand that on a practical level, but on a philosophical level, these are the kinds of things that I think send a wrong message to students. We believe in kids, and I think the vast majority of teachers out here do. I think the masses of teachers believe in kids and believe kids will do the right thing.”

Patrick Sasser, alumnus 2003 and a teacher at the Career Center, believes the element pushing all these changes is evident, and that it poses a huge threat to the culture of the school and to “Freedom with Responsibility.”

“I think the equity piece is what really poses a problem for freedom with responsibility,” Sasser said. “Now that there are three high schools, there is always talk about equity. What does Hickman have? What does Battle have? What does Hickman do? What does RBHS do? What does Battle do? People want to know that kids are getting a similar high school experience no matter what high school they are at, so I think that has the most potential to basically eliminate freedom with responsibility. When you try to create equity across all three buildings and across all three schools, then that is when you have to eliminate things like AUT. [Since] other schools are not doing it, I think it will be eliminated.”

The addition of the freshmen is a huge change in the eyes of people like Sasser, Webel and Graham. Webel said the first thing he noticed when he returned from Boston was the presence of the ninth grade class, and he said this has made a huge impact on the school.

“That has changed the culture for sure. I am not saying negatively, ultimately, but I feel like we have to be more intentional, and I guess set more boundaries and teach ninth-graders how to become high school students,” Webel said. “Just even that one year between a 14 and a 15-year-old, [and] a 16 and a 17-year-old I think makes a huge difference in what they are able to handle and the level of freedom they get, so I feel like that has been a big change.”

However, the freshman class was not the only addition that the school had when they joined. Many teachers from the middle school level and the now non-existent junior high school level joined the school as well.

While Webel worries about the future of the school and the future of “Freedom with Responsibility,” he also has hope in the new teachers who came to the school with the freshmen.

“There are a lot of new teachers. There are a lot of teachers that I didn’t know three years ago that are here now, and I am trying to listen to them and [trying to] see what they think the school is about or education should be about,” Webel said. “I can’t just assume that everyone kind of just gets [the school]. I think there has been a sort of learning curve as well for the teachers to understand how [this school] is different from the schools they came from, and that is a challenge, I think, as we’ve adjusted to the influx of new teachers.”

Webel believes if the concept of “Freedom with Responsibility” is not understood and accepted by the new wave of students and the new wave of teachers, then it will be in danger.

“I do think that the upperclassmen do a good job helping the freshmen and sophomores sort of get it, get what [this school] is about, but part of that also is having teachers that went to school here too,” Webel said. “I know what [the school] is about because I grew up here, and then I learned more about it as a teacher [here].”

Webel said because he went to school here, and he knows why some of the changes that occurred at his time here happened the way they did, he attempts to share that knowledge with students and with new teachers who may not know exactly why things are they way they are.

“You have to be intentional about making sure the ninth-graders understand [the freedoms] so that when they are seniors, they are telling their ninth-graders about it, too,” Webel said. “It is sort of a self-perpetuating organic spirit of the school.”

Graham said there are plenty of great teachers who did not attend this school as students who fully embrace what the school stands for. However, both he and Webel believe they, as teachers who went this school as students, are able to understand what the school is about from the perspective of the students.

“I think as someone who went to school here and is now a teacher here, I think it gives me a deeper understanding of what the students are experiencing with freedom with responsibility, with AUT, but it doesn’t necessarily make me a better teacher because I can do that,” Graham said. “It just means that I have a deeper sense of empathy for and an understanding of what the school means to me.”

In their years of high school, both Webel and Graham say they were not the worst of the worst or the best of the best in their classes, but largely in the middle.

“I was kind of a punk kid, and I did my own thing, and I didn’t want to play by the rules, and I was always hanging out with my three buddies, and we were kind of goofing off all the time,” Webel said. “I remember just being challenged by individual teachers, and they took an interest in me and cared for me beyond just a kid in the classroom, so I feel like this is something I try to do as well, actually care about kids and get to know them … I want them to be successful as much as possible, and this is, to me, part of giving back and building this school.”

Graham and Webel both believe the system of “Freedom with Responsibility” works because it worked for them. Webel wants his students to be as successful as possible, partly because he believes they have a right to live in a school environment that teaches its students how to use freedom responsibly.

“I think [I have] a deeper understanding of how beneficial [freedom with responsibility] can be and the system can be if you just let it work,” Graham said. “I was one of the masses in the middle. I was neither an AP student nor an F student. I was in the middle. [Freedom with responsibility] worked well for me, and it works well for the vast majority of the students here. That, to me, makes me want to fight for their ability to have the same types of rights and freedoms that I did.”

This school has experienced change time and time again. Each wave of students who walked in these halls faced different changes. Webel’s generation saw the introduction of block schedules and team-taught classes. Sasser’s saw the idea of sophomore advisory take effect.

This generation saw the implementation of Bruin Block, among many other changes. With all of these countless changes put into place in the school, Sasser, Webel and Graham all agree on one thing.

“The feel of [this school] has not changed to me at all,” Graham said. “It is still student-centered and I think that it has been amazing that we have been able to keep it as student-centered as we have [over time].”

By Abdul-Rahman Abdul-Kafi[TS_VCSC_Icon_Flat_Button button_style=”ts-color-button-emerald-flat” button_align=”center” button_width=”100″ button_height=”50″ button_text=”Previous” button_change=”true” button_color=”#ffffff” font_size=”18″ icon=”ts-awesome-chevron-left” icon_change=”true” icon_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_html=”false” tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-top” tooltipster_offsetx=”0″ tooltipster_offsety=”0″ margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″ link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bearingnews.org%2F2015%2F04%2Fsecond-chances%2F|title:Second%20Chances|”]This article is the first in a series. Select “Next” to view the next article in the series, or “Previous” to view the preceding article.[TS_VCSC_Icon_Flat_Button button_style=”ts-color-button-emerald-flat” button_align=”center” button_width=”100″ button_height=”50″ button_text=”Next” button_change=”true” button_color=”#ffffff” font_size=”18″ icon=”ts-awesome-chevron-right” icon_change=”true” icon_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_html=”false” tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-top” tooltipster_offsetx=”0″ tooltipster_offsety=”0″ margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″ link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bearingnews.org%2F2015%2F04%2Ftrapped-inside-the-mind%2F|title:Trapped%20Inside%20the%20Mind|”]

1992: The PAC, or the Performing Arts Center, and three new science classrooms are added to the school. A year before, the Soviet Union collapsed and in the Middle East, the Persian Gulf War ended.

1994: School bell schedule changes from a 50-minute, seven classes a day schedule to a 95-minute, four blocks per day every other day schedule. DUTs, or Daily Unassigned Times, change to AUTs, or Alternating Unassigned Times. Nixon passes away after suffering a stroke.

2000: Sophomore advisory is introduced for the first time and seven Science classes, seven Foreign Language classes, eight English and Social Studies classes, the media center and three new computer labs are added to the school. George W. Bush defeats Al Gore in the presidential election.

2013: School start times change to a three-tiered system, making high schools start an hour later. Freshmen join the high schools and eighth-graders join the middle schools. A daily Bruin Block schedule is introduced for the incoming freshmen and sophomore classes. A new gym is added along with a new wrestling room and a new weight room. The old wrestling room’s space is turned into four math classrooms and the old weight room is turned into a dance studio for the Bruin Girls. This same year, the Boston Marathon bombing happens, killing five, including an eight-year-old boy, and injuring 280 others.

2014: A new buzz-in system is introduced to all CPS schools. ISIS emerges in Iraq, splitting the nation in two and spreading massive fear throughout the population. It is no surprise that after 42 years, the school, and the world in general, has changed. The culture of this school from its start has been focused around change, according to Matt Webel, a Social Studies teacher here who also attended high school from 1993-96 in this very building. However, with time, everything eventually changes, because as time naturally progresses, so does everything along with it.

Webel’s “big change” was block scheduling. He experienced the same school that exists today; he attended a school that yearned for change, a school that would rather fail after trying than not try at all.

“Bruin Block [is] sort of the current attempt [here] to implement something that is good for kids. We are two years into it now, and I think that we have seen challenges to the system and some anger from students that don’t like it and some frustration from teachers who don’t like it,” Webel said. “And then on the other side you also see kids that say that it is a great experience that they have had and teachers that have said the same thing, so I think the hallmark of [this school] is that we listen to all of these concerns and opinions from all of the constituents, and then we make a good decision moving forward.”

Three years ago, Webel moved to Boston after teaching at this school for almost a decade. This school year, he returned to teach here again. Even before that, Webel attended high school here from 10th to 12th grade in the mid-90s and was a student when the bell schedule changed in 1994.

“I was a sophomore becoming a junior, so I don’t remember anyone asking me what I thought or soliciting my opinion or student opinions, which doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. I just don’t remember it,” Webel said. “I think initially I was put off by the amount of time that I had to spend in one place and back then, I think it was still a very stand and deliver model of education, so it was a lot of sitting in desks and listening to teachers, so over the course of time I think we have had to figure out ways to adapt our teaching to take into account the fact that these are longer classes.”

Eventually, after a few months of this change, Webel said he began to like the new model mainly because of two teachers who made it seem fun for him a student. In his sophomore year, Webel had Bill Priest as his World History. When the schedule change happened, the school also joined together all English and social science classes into block classes with two teachers.

“Junior year, I had Mr. Priest and [Michael] Bancroft for the first ever combined, interdisciplinary course of U.S. studies, and I just remember it was the first time that I had ever seen two teachers in the same classroom and the dynamic relationship that the two of them had, not only with each other, but they were able to have with us as students I thought created a much richer classroom environment, especially since I had Mr. Priest a year before,” Webel said. “You could tell they had a good relationship with each other. They appreciated each other’s intelligence and perspective … and we would see them interact and even laugh with each other about stuff that was happening in class and I could tell that they enjoyed what they were doing. From that moment on, I think really early on, and it was a lot because of the dynamic personalities of both of these teachers and how they related to each other, but I was sold on the model, and I have believed in it ever since.”

Webel said the way the school changed during his time as a student is similar to the way the school is changing currently with, for example, Bruin Block or the later school start times.

“I think, like anything at RBHS, we don’t exactly know how [the change] is going to go. We believe in [the change] in theory, or we like it in theory, or there are certain things that we want to adapt to our system, so I think block scheduling is like that, and I think integrated curriculum is like that and Bruin Block fits in that same category,” Webel said. “[These are] things that we think are going to be great for kids and great for our school and building a culture. We see a problem or a need, and we try to address it. So I think all of the changes that we are talking about have been implemented with good intentions, but I also think at RBHS we have the humility to look back and say ‘well maybe that decision didn’t work out the best way,’ or maybe ‘we had good intentions, but we couldn’t figure out a way to implement it.’”

With all of these changes, Webel believes the overarching DNA of the school will always stay the same. As long as this element is in place here, this school will continue to be the unique school that it has always been.

“Freedom with responsibility was still the motto we talked about all the time. We still got flogged from the community for allowing kids to leave campus for lunch, so those were the principles that were there,” Webel said. “But I think over time, we have developed them more and figured out ways to talk about them and express them to the community. Because in the beginning it was like we just do it and there was no real reason … but over time, we are able to see the benefits, as 25 years of kids, or however old the school is, have gone through the system and have been able to come back and talk to us about how [it] prepared [them] for college.”

Part of the reason why the DNA of the school is still unchanged is because of the many generations of students who have walked in these halls. Fellows Mentor David Graham, who helps and mentors masters students from the University of Missouri who work here, believes that the vast majority of the student body of this school today is similar to the vast majority of the student body when he went to this school 29 years ago in terms of academics. However, he has noticed a change in regard to the involvement of students.

“More students went to more athletic events and dances and things like that [when I went to school here],” he said. “I don’t know what the cause for that is, the disconnect. It is somewhat of a change, not a huge change, but there are a smaller percentage of the students going to the games than when I was in school, and plays and choir concerts and all of the extracurricular stuff.”

The changes RBHS has experienced in the past couple years worry Graham. He believes most students will do the right thing if given the choice between good and bad.

“The vast majority of our students are going to be just fine handling freedom with responsibility, but it is the extremists that make things tough for the masses,” Graham said. “I think that to people who went to traditional high schools, it is uncomfortable to see a school like ours that really does believe that kids would do the right thing first, and if you look at the vast majority of the building since the time it opened in 1973, they have done just fine all the way through to today.”

However, Graham thinks adding things like locked doors and cards to get people in and out of the building, while necessary, is a small step in the wrong direction.

“It wasn’t done because this building decided it. The district decided that, and the district decided that for insurance purposes,” Graham said. “We have to do that, and I understand that on a practical level, but on a philosophical level, these are the kinds of things that I think send a wrong message to students. We believe in kids, and I think the vast majority of teachers out here do. I think the masses of teachers believe in kids and believe kids will do the right thing.”

Patrick Sasser, alumnus 2003 and a teacher at the Career Center, believes the element pushing all these changes is evident, and that it poses a huge threat to the culture of the school and to “Freedom with Responsibility.”

“I think the equity piece is what really poses a problem for freedom with responsibility,” Sasser said. “Now that there are three high schools, there is always talk about equity. What does Hickman have? What does Battle have? What does Hickman do? What does RBHS do? What does Battle do? People want to know that kids are getting a similar high school experience no matter what high school they are at, so I think that has the most potential to basically eliminate freedom with responsibility. When you try to create equity across all three buildings and across all three schools, then that is when you have to eliminate things like AUT. [Since] other schools are not doing it, I think it will be eliminated.”

The addition of the freshmen is a huge change in the eyes of people like Sasser, Webel and Graham. Webel said the first thing he noticed when he returned from Boston was the presence of the ninth grade class, and he said this has made a huge impact on the school.

“That has changed the culture for sure. I am not saying negatively, ultimately, but I feel like we have to be more intentional, and I guess set more boundaries and teach ninth-graders how to become high school students,” Webel said. “Just even that one year between a 14 and a 15-year-old, [and] a 16 and a 17-year-old I think makes a huge difference in what they are able to handle and the level of freedom they get, so I feel like that has been a big change.”

However, the freshman class was not the only addition that the school had when they joined. Many teachers from the middle school level and the now non-existent junior high school level joined the school as well.

While Webel worries about the future of the school and the future of “Freedom with Responsibility,” he also has hope in the new teachers who came to the school with the freshmen.

“There are a lot of new teachers. There are a lot of teachers that I didn’t know three years ago that are here now, and I am trying to listen to them and [trying to] see what they think the school is about or education should be about,” Webel said. “I can’t just assume that everyone kind of just gets [the school]. I think there has been a sort of learning curve as well for the teachers to understand how [this school] is different from the schools they came from, and that is a challenge, I think, as we’ve adjusted to the influx of new teachers.”

Webel believes if the concept of “Freedom with Responsibility” is not understood and accepted by the new wave of students and the new wave of teachers, then it will be in danger.

“I do think that the upperclassmen do a good job helping the freshmen and sophomores sort of get it, get what [this school] is about, but part of that also is having teachers that went to school here too,” Webel said. “I know what [the school] is about because I grew up here, and then I learned more about it as a teacher [here].”

Webel said because he went to school here, and he knows why some of the changes that occurred at his time here happened the way they did, he attempts to share that knowledge with students and with new teachers who may not know exactly why things are they way they are.

“You have to be intentional about making sure the ninth-graders understand [the freedoms] so that when they are seniors, they are telling their ninth-graders about it, too,” Webel said. “It is sort of a self-perpetuating organic spirit of the school.”

Graham said there are plenty of great teachers who did not attend this school as students who fully embrace what the school stands for. However, both he and Webel believe they, as teachers who went this school as students, are able to understand what the school is about from the perspective of the students.

“I think as someone who went to school here and is now a teacher here, I think it gives me a deeper understanding of what the students are experiencing with freedom with responsibility, with AUT, but it doesn’t necessarily make me a better teacher because I can do that,” Graham said. “It just means that I have a deeper sense of empathy for and an understanding of what the school means to me.”

In their years of high school, both Webel and Graham say they were not the worst of the worst or the best of the best in their classes, but largely in the middle.

“I was kind of a punk kid, and I did my own thing, and I didn’t want to play by the rules, and I was always hanging out with my three buddies, and we were kind of goofing off all the time,” Webel said. “I remember just being challenged by individual teachers, and they took an interest in me and cared for me beyond just a kid in the classroom, so I feel like this is something I try to do as well, actually care about kids and get to know them … I want them to be successful as much as possible, and this is, to me, part of giving back and building this school.”

Graham and Webel both believe the system of “Freedom with Responsibility” works because it worked for them. Webel wants his students to be as successful as possible, partly because he believes they have a right to live in a school environment that teaches its students how to use freedom responsibly.

“I think [I have] a deeper understanding of how beneficial [freedom with responsibility] can be and the system can be if you just let it work,” Graham said. “I was one of the masses in the middle. I was neither an AP student nor an F student. I was in the middle. [Freedom with responsibility] worked well for me, and it works well for the vast majority of the students here. That, to me, makes me want to fight for their ability to have the same types of rights and freedoms that I did.”

This school has experienced change time and time again. Each wave of students who walked in these halls faced different changes. Webel’s generation saw the introduction of block schedules and team-taught classes. Sasser’s saw the idea of sophomore advisory take effect.

This generation saw the implementation of Bruin Block, among many other changes. With all of these countless changes put into place in the school, Sasser, Webel and Graham all agree on one thing.

“The feel of [this school] has not changed to me at all,” Graham said. “It is still student-centered and I think that it has been amazing that we have been able to keep it as student-centered as we have [over time].”

By Abdul-Rahman Abdul-Kafi[TS_VCSC_Icon_Flat_Button button_style=”ts-color-button-emerald-flat” button_align=”center” button_width=”100″ button_height=”50″ button_text=”Previous” button_change=”true” button_color=”#ffffff” font_size=”18″ icon=”ts-awesome-chevron-left” icon_change=”true” icon_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_html=”false” tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-top” tooltipster_offsetx=”0″ tooltipster_offsety=”0″ margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″ link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bearingnews.org%2F2015%2F04%2Fsecond-chances%2F|title:Second%20Chances|”]This article is the first in a series. Select “Next” to view the next article in the series, or “Previous” to view the preceding article.[TS_VCSC_Icon_Flat_Button button_style=”ts-color-button-emerald-flat” button_align=”center” button_width=”100″ button_height=”50″ button_text=”Next” button_change=”true” button_color=”#ffffff” font_size=”18″ icon=”ts-awesome-chevron-right” icon_change=”true” icon_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_html=”false” tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-top” tooltipster_offsetx=”0″ tooltipster_offsety=”0″ margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″ link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bearingnews.org%2F2015%2F04%2Ftrapped-inside-the-mind%2F|title:Trapped%20Inside%20the%20Mind|”]