The last section, though, seems to be the most challenging for students, according to annual statistics.

For me, the science section of the ACT was always one of the hardest, and I blew through several practice tests before I got a decent score. But the problem applies to many students who take the test. According to research findings published by ACT, only 36 percent of test takers met the ACT College Readiness Benchmark for science as of 2013.

These findings indicate that more than two-thirds of students did not have the scientific knowledge they needed to do well in college, and this was after these individuals had graduated from four years of high school education.

This raises a red flag for all American education systems. The U.S. education system is in dire need of a reform, from top to bottom. There are many ways teachers can do their part to help their students learn better; change always starts small, but it needs to start somewhere.

According to a study by The Journal of Effective Teaching, “active techniques do aid in increasing learning as in-class activities led to higher overall scores while lecture led to the lowest overall scores.” The study, titled “Learning by Doing: An Empirical Study of Active Teaching Techniques,” tested four different types of teaching techniques: lectures, demonstrations, in-class activities, and discussions.

The report concluded that in-class activities tend to cause better retention of information in students, and lectures often led to the worst performance in students. But along with these conclusions, the study also stressed that a perfect balance of the four methods of teaching are needed for a successful classroom experience. A good teacher would use multiple strategies in order to ingrain the course material into his or her students’ brains.

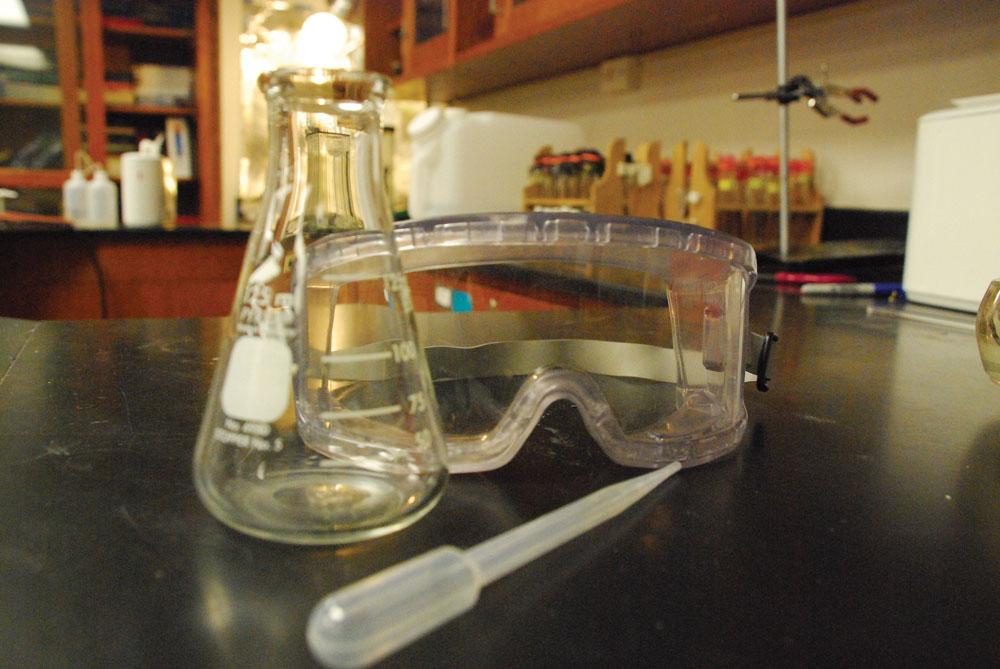

In order to boost the nation’s scientific capabilities, teachers should change the structure of their lesson plans in a way that incorporates more hands-on activities that directly correspond with class notes and lectures.

This way, teachers can enforce the information students learn through traditional learning methods, such as reading textbooks and taking notes, with experiences the students are more likely to remember further on down the road. During tests, students will then be more likely to recall the information they learned through enjoyable activities, because lectures that they find boring might not be effective at embedding the necessary course material into their heads.

Another reason students cannot learn science efficiently just by memorizing formulas and random facts is because science is much more than learning a few pieces of information through this method of rote memorization; science is an ever-changing entity. It is not comparable to subjects like English or history, because science does not require students to know the role of the British in the French and Indian War, or how to properly use a proverb in a sentence. Although scientists rely on a knowledge of scientific facts from which they can base their thinking off of, they usually apply what they know to the current task at hand.

Scientists don’t spit out the information they learned in high school on a regular basis; they are thinking people who challenge old theories and test out new ideas of their own. If those skills are needed in a science-related career, then our education systems should be stressing their importance.

The U.S. has the potential to develop the minds of the next generation’s top scientists. It has all the right ingredients for it; all it needs now is the right recipe. By changing the way our science instructors enforce learning through an increase in hands-on activities available to students, our nation will be one step closer to becoming comparable to the caliber of science education in other nations. In this manner, the U.S. can reform the curriculum of its school systems efficiently.

On an international scale, it is entirely possible for American students to eventually overtake the current achieving countries, and their excellence in science education can not only bring up the prominence of the U.S. on a global scale, but it can also prepare our youth for the technologically-advanced future. But in order for this reform to happen, we must take initiative. This reform can only start if instructors change the way in which they teach, with their students’ best interests in mind.

By Afsah Khan

Abby Kempf • Apr 8, 2014 at 10:58 am

Science has always been my hardest ACT section, even though I do well in science classes at school. This could definitely be because science courses I have taken do not require me to actually understand and perform science experiments but instead regurgitate facts mindlessly.