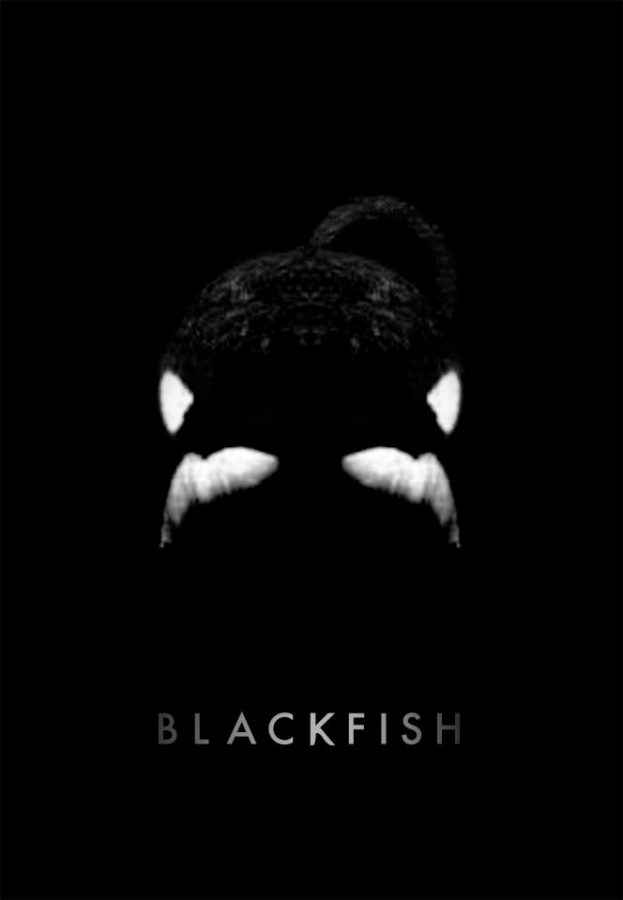

Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s Blackfish is one of the most important documentaries I’ve seen in the past five years. It’s a film every animal lover should see, and one that drastically alters any happy childhood memories you might have of Seaworld and Shamu.

The documentary opens with a stark black screen interspersed with clips of swimming captive killer whales. In the background, a recording plays of the 911 call sent from Seaworld Orlando after one of the park’s popular whales, Tilikum, killed and subsequently began devouring his senior trainer, Dawn Brancheau.

From there on, the film is an incredibly intimate look at killer whales, their trainers, and the lives that have been affected by keeping these surprisingly intelligent massive marine mammals in captivity. Cowperthwaite’s team did an impressive job of hunting down the kind of characters that are rarely found outside of fiction; a band of self-termed “Canadian sea cowboys”, a motley collection of intensely likable ex-Seaworld trainers and even an aging former orca-catcher who Cowperthwaite described as a real-life version of the shark hunter from Jaws. It’s Tom Crow, the orca-catcher, whose testimony first drives home the film’s message. A navy vet who saw action during the Latin American revolutions of the mid-twentieth century, Crow tearfully explains that after hearing the family of whales clustered around his boat scream and wail as their children were dragged away, he realized that hunting killer whales was the worst thing he’d ever done.

The real star of the show, however, is Tilikum, the killer whale involved in the death of three people. A fair chunk of the film is dedicated to telling Tilikum’s tragic life story, and as you hear the testimonies of marine biologists discussing killer whales’ intelligence and look into Tilikum’s eyes, you begin to see him as less of a dumb beast and more of a tortured soul.

Blackfish is an emotional film, and not just because “Boo hoo, those poor animals,” although after watching the film its hard to ever think of orcas as anything but thinking beings ever again; no, it’s also an emotional film because it explores the ways in which these whales have touched human lives. We hear ex-Seaworld trainers discuss the bonds they felt they had with their whales, and we also hear the heartbreak in their voice as they describe the atrocities they saw committed toward these orcas and the pain in losing some of their friends in attacks sugarcoated as accidents. Witnesses and family members of victims are also interviewed, and their tearful voices add another layer of humanity onto this bleak but beautiful tale of the deep.

The whole film oozes style, interspersing its interviews with artistically animated court room reenactments and some of Seaworld’s commercials over the past few decades. These clips help keep the movie moving and serve as excellent transitions from point to point and concept to concept. They also lend it a slightly lighter air, as does the film’s touching conclusion, which ultimately transforms the story into one of hope for a brighter future and redemption.

This masterpiece is a movie that made me want to go out and help make a change. It made me feel connected to other individuals in a uniquely original way, and not all of them were human. It’s a film that I would see again, and hopefully, when it arrives in theaters across the country this summer and airs on CNN this fall, I will.

By Jake Alden

‘Blackfish’ teaches needed lesson

March 3, 2013

jmventre • Mar 10, 2013 at 3:01 am

Jake, this review blew me away, and like John Hargrove, above, who might be an intensely likable x seaworld trainer, this is by far the most precise review I’ve read. Personally, I’m glad you survived the hi velocity golf balls, because you assimilated the film and wrote a tremendous and accurate review. Thx

April Hargrove King • Mar 8, 2013 at 11:56 am

I can’t wait to see Blackfish! I’m so proud of the trainers who are speaking out…my cousin being one of them. Great review!

John Hargrove • Mar 8, 2013 at 11:04 am

Jake, I have read many reviews at this point and this hands down is the one I like the most. You have demonstrated that not only do you completely get what is going on but that you are also a talented and skilled writer capable of drawing in and influencing your readers just like the film ‘Blackfish’ did. Thank you.

Monica Gilbert • Mar 8, 2013 at 9:44 am

I’m with Kevin, Jake. Excellent review. As an anti-cap activist, it is refreshing to see the light come on when someone realises that orcas, and all cetaceans, are thinking self-aware non-human animals and should not be incarcerated as they are in marine amusement parks like SeaWorld where they are forced to sing for their supper.

I hope you do go out and help make a change. Thank you for your review.

Kevin • Mar 7, 2013 at 10:25 pm

Thank you for sharing your insights on this important film….this is an excellent review!