Independence

In February, The ROCK staff looked at the concept of independence in high school life.

Freedom. Perhaps the most stirring of ideals, it has powered wars and revolutions, invention and migration. Our country is founded on the ideal of independence, of freedom; a whole day of the year is dedicated to its celebration.

But like many ideals, independence is a concept that can be muddied, repurposed and lost in the sounding hall of rhetoric. Often times it is necessary remember the meaning of independence — those who come here to find it.

Adolescents gain independence from parents as they transition through high school

Senior year is a time when many students want to take easy classes and enjoy their last year of high school as much as they can. But for senior Kreagan Carbone, every day is a busy one. She attends classes at RBHS, takes college-level courses and juggles having a job at Claire’s, being a hostess at Jazz and having a side job at her mother’s company.

Her fast-paced life is relatively new to her, though, and she only recently gained the independence allowing her to take on such responsibilities after becoming financially self-sufficient and getting her own car.

Throughout her high school career, Carbone virtually stopped relying on her parents. Her freshman year, though, was like most of her classmates’, spent with little-to-no liberty.

She couldn’t drive, and she didn’t have a job. But after obtaining these privileges, and in turn gaining freedom from her parents, Carbone reflects on why freedom is necessary for her and for her peers.

“I think independence is important because … being able to rely on yourself, and not having to rely on others, is something that a lot of people strive for, because a lot of people don’t want to ask other people for help or for favors,” Carbone said. “So I think that independence is important mostly because we are able to do things on our own and have that accomplishment of being self-sufficient and not having to rely on everybody else.”

Marcy Kielczynski, a therapist in Cranford, New Jersey, said it is normal for teenagers to feel a need for freedom around the time they come into high school, usually because of pressure from their peers.

“Between 15-17 years, youth enter a developmental stage called middle adolescence. Achieving independence from their parents is particularly important to a middle adolescent,” Kielczynski said. “While they still need love and acceptance by their parents, they want to mature and therefore hide such needs. … They often conform to ‘peer pressure’ as a way of gaining independence.”

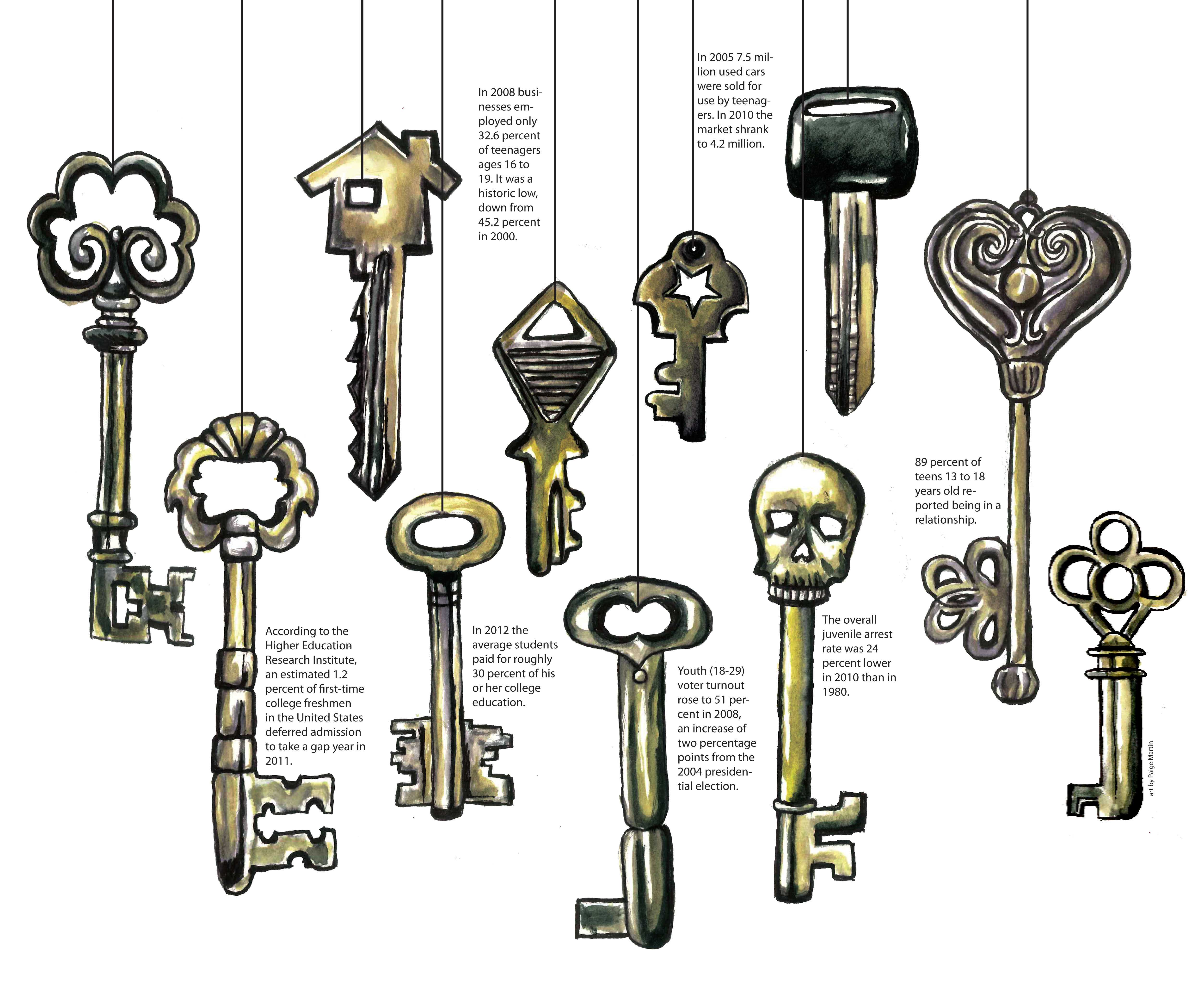

However, not all students are as self-reliant as Carbone. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, only 16 percent of high school students were employed in 2010. In other words, many students, including sophomore Maha Hamed, still feel financially dependent on their parents, and this hinders their overall freedom.

“If it’s like with my own money, then I think ‘Oh, that’s a little too expensive.’ But if I’m with my mom, then I want everything in the store, and I don’t even look at the price,” Hamed said. “So if it’s my own money, I’m almost afraid to buy it, because I think to myself, ‘Is it really worth it?’”

Similar to how Hamed is more open to using her mother’s money, according to a Teens & Money survey conducted by Koski Research in 2011, on average, 28 percent of teens owe their parents $252. The totals rack up from teens borrowing and carelessly spending money that isn’t necessarily their own.

Indeed, the majority of the money Hamed spends comes right out of her parents’ pocket, and Hamed’s financial dependency is not something she foresees as being short-lived.

Hamed stated that her parents will pay for her car, insurance, gas and even tuition all the way through college in the near future.

Hamed is not the only one expecting such dependency. According to the Mail Online, at dailymail.co.uk, on average, parents find themselves spending almost $10,000 per child over the course of their lifetimes to pay for education, weddings, holidays and also housing.

But such reliance is usually expected by parents, as a survey conducted by the Daily Mail revealed that. On average, parents did not expect their children to become financially independent until they reached the age of 38, and more than a quarter of parents said they believed their children would always need financial support from them. On the other hand, Hamed believes the prospect of a potential job, like Carbone, might alter this reliance on her parents to provide for her in every means.

“I think the only time I’ll really be financially independent is when I have a job, because if I have no source of income, I’m just going to rely on my parents,” Hamed said. “And if you really think about it, with the economy now, it’s hard for even adults to get jobs. So I might be relying on parents for longer than I think.”

Kielczynski recognized the importance of being financially self-sufficient for teenagers, mostly since there is a feeling of accomplishment that comes with being able to pay for one’s own needs.

“Financial independence will allow the youth to become aware of the cost of living and realize what decisions they will have to make in order to be able to become financially successful,” Kielczynski said. “It also may improve their self-esteem because they are not relying on their parents as much.”

In fact, reliance on their parents may be a recurring theme for teens. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the number of high school students who held jobs declined from 32 percent in 1990 to 16 percent today.

The study states the availability of jobs has decreased, while the focus on school and college has increased for teens. This in turn will cause the amount of teens relying on their parents for money to escalate.

Although Carbone does not rely on her parents for leisure money, having three different jobs doesn’t prevent her from focusing on her education and preparing for her future.

She took four online classes and is a part-time student this year at RBHS so she can take dual-enrollment classes to prepare for classes in college.

Carbone thinks her independent lifestyle also helps her brace for life during and after college. She thinks she will be better off because of her self-sufficiency in high school and the experiences she has gained from her jobs and college-level classes.

“[If] you’re allowed to be dependent and you choose, instead, to be independent and try to grow out of that, then in the long run, later in life, when you don’t have that choice of dependency, it’s easier for you to stand on your own two feet,” Carbone said. “So you’re more able to accommodate every aspect of being independent, so it’s more gradual than a big shock right away. [If] you spend your whole life being dependent and … you’re thrown out one day, it’s kind of a bigger shock.”

Carbone’s belief of balancing self-reliance during high school while paying special attention to planning for her future is a belief shared by several of her peers, including sophomore Saja Necibi.

Necibi thinks that students gradually gain freedom as they progress through high school. She already notices her parents granting her more liberties, such as letting her spend more time with her friends after her first year of high school.

“Compared to freshman year … I think my parents trust me more,” Necibi said. “If I say I want to go hang out with somebody, they trust that I won’t take too long. I won’t do anything crazy or stuff like that.”

However, although Necibi faces the same problems as Carbone did in her early years of high school, Necibi plans on waiting until senior year to get a car. She doesn’t anticipate getting a job until after graduation, although many students, including Carbone, consider having a job a big step to independence.

Students such as Carbone and Necibi consider a car to be a symbol of independence, even if the student does not buy the car with his or her own money, a notion that is reflected by the fact that several teenagers do not have a job.

According to a study conducted by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 73 percent of teenage drivers own their own cars. Necibi also looks forward to getting a car and obtaining a degree of freedom from her parents.

“I think for me, honestly, getting a car would be a really big thing ‘cause I feel really dependent on my parents now. [I have to tell them], ‘Oh, can you pick me up at four today,’ or some of my club meetings … meet at seven at night, and my mom is tired and can’t take me,” Necibi said. “I feel like once I get a car … I’ll feel that big jump [to independence].”

Kielczynski said getting a car is a big step in the road to freedom for teenagers because of the independence that comes with it.

“When an individual is able to drive [or] own a car and … get a job, this allows them to feel more independent because they do not have to rely on their parents or others for financial assistance or transportation,” Kielczynski said. “During this stage of development, teenagers seek out ways of fitting in. If they have a job, they may be able to partake in more social experiences or buy more materialistic items [such as] clothes, jewelry [and] technology, which will make them feel more independent.”

Overall, Carbone sees her independent lifestyle as beneficial to her and her family. She feels as though being self-reliant at an earlier age allows students to get a taste of life after high school and ultimately prepares them for being successful without their parents’ support.

“I see [independence] as a completely positive thing, just because I feel like it … prepares me for the world,” Carbone said. “Kids who have everything handed to them … and everything paid for, when they’re … in the real world, they don’t have their parents, and they’re just lost.”

She also thinks gaining freedom in high school comes with big responsibilities and expectations. While many of her high school peers want freedom from their parents and the ability to live on their own, Carbone does not think anyone could handle the self-sufficient lifestyle she has.

“A lot of people struggle with transitioning into having your own life and having your own responsibilities, and a lot of people can’t handle those responsibilities … and that’s why I think a lot of people, when they move out, they move back in,” Carbone said. “They weren’t able to handle the shock of having to be on your own and having to do your own thing and providing for yourself.”

Kielczynski agreed that the high school years are an important time for personal growth for teenagers, and it is part of the natural process to learn from mistakes and gain responsibility along with the freedom they obtain.

“Gaining independence from parents during adolescence is important in order to gain autonomy,” Kielczynski said. “One of the most important skills of a teenager is learning the skills that will allow them to make healthy and positive choices.”

Along with preparing her for a future where she will make certain decisions without her parents, this freedom allows Carbone to manage her time more wisely than she was able to before. She feels as though her liberty can be credited for her well-rounded lifestyle.

“[I like] having the liberty to do a little more of what you want instead of having to work on other people’s schedules, because [before], I couldn’t go anywhere until my mom got off work,” Carbone said. “No one was able to come home and get me, but now I kind of have that freedom … and I feel like a lot of kids just want that little bit of time to be able to be themselves.”

By Afsah Khan and Manal Salim

Culture transition brings independence

Senior Tar Nar came to the United States two years ago, and it’s easy to tell. He’s got that strange mixture of confidence and quietude that comes with knowing English just well enough to be proud.

He’s one of the Karen people, an ethnic group originating in Myanmar that has been oppressed by the brutal military regime there for the last century and has sought freedom from them without much success.

Several hundred thousand Karenni worldwide have been burned out of ancestral villages and scattered, and Nar is part of the diaspora that has reached the United States.

At RBHS, Nar is part of a group of almost three dozen recent immigrants in English Language Learner teacher Lilia Ben-Ayed’s absolute beginners class. It’s made up of an ethnically diverse group of students – refugees from Iraq and Burma sit side by side with the son of a successful Jordanian businessman. Nar’s story begins in Thailand.

“I was born in Thailand … in a city,” Nar said. He is “from a refugee camp because of the problem with the Karenni in Thailand. I stayed maybe 16 years in the camp. Every day I ate rice.”

Nar lives with his aunt, whom he came with two years ago. His five brothers and sisters, along with his parents, are still refugees in Thailand. He said the hardest part of going to the United States was leaving them behind.

“They did not [go with] the U.N. I still talk to them on the phone sometimes. The last time I saw them was when I left,” said Nar, who always reminds his family he still thinks about them. “When I am on the phone I say, ‘me and you, me and you.’”

Freshman Hamzah Quedh is from Jordan; he’s the son of that Jordanian Businessman. He and Nar are a far cry from each other, coming from different locations geographically, socioeconomically and culturally, but they have one thing in common: they came to the United States seeking independence. Quedh said for him it was a chance to escape a stale Arabic background.

“In all [the] Arab world, if they see you have a lot of money– your T-shirt is Polo, your watch is Rolex – they will love you. But here, they don’t care. They don’t look to that; they don’t care what you’re wearing. They just look to your inside. I like that. In Jordan, if you don’t have money, no one will love you, no one will talk to you. This is a problem in the Arab world.”

Quedh and Nar may come to the United States to find a better life. Refugees and travelers still face many challenges among moving to the States, but chief among them is language.

Ben-Ayed said it can be overwhelming for many students to move to an environment where a language barrier separates them from jobs, information and simple interactions with peers.

One of the largest issues for students is being on time; in other countries, time is flexible, and Ben-Ayed said students often learn the United State’s rigidity the hard way.

“They get overwhelmed in hallways. That’s huge … being in the hallways, not speaking the language is overwhelming for them. The first day we visit the cafeteria, so everything is new. That’s a big culture shock, and they start to try things,” Ben-Ayed said. “It’s scary if you don’t know what’s going on. Even the schedules, the first week is intense on just routines. Teaching the culture.”

After the initial culture shock, students settle into learning the language of the land. Quedh believes that learning new languages is paramount in his own education. He and his father may move again, he said. So to learn as much of English as he can is important on a personal level.

“I am excited to learn every language. Maybe we will move to another country; maybe I will see someone who doesn’t speak my language,” Quedh said. “I should speak to him in his language. Arabic is a very hard language. But English, if you know the letters and the meanings, you will speak.”

Quedh has the ability to learn at his leisure, though he wants a job. Ben-Ayed said this is not the case for most. Once off the six months of government aid allotted to refugees, many, especially adults without access to English classes, struggle to get enough food to eat and pay rent.

Families come to Columbia because of its sizable refugee population. Nar, for instance, came to Missouri because several Burmese refugees were already here.

“Last year we had a Burmese family. They came to Columbia, but after six months here they moved out. They could not find jobs. So if they have friends, they’ll come here to Columbia, and they’ll stay if they can find jobs.” Ben-Ayed said. “It’s very difficult for the parents of my students to find a job. It’s hard to get a job with zero English skills, so it’s a big struggle.”

Nar is one of the lucky ones. His stable job cleaning rooms at a Comfort Inn at 2904 Clark Lane provides him with enough income to pay for the essentials, and he’s aware of it. Though the refugee camp in Thailand allowed more freedom and had admittedly better weather, he said, his life in America was still improved.

“I had a best friend that was a boy in the camp. We walked together; we played games together; we walked through the forest together. … In the United States, I don’t have time. I go to school, I have [a] job,” said Nar, who likes his work. His parents said, “‘Come to the United States and learn.’ … I come to the United States, and I can learn. I have a job here and every night in the Comfort Inn, [I’m] cleaning.”

Quedh said his largest struggle was to find friends who could listen past the language barrier. In America, he said, there is much to be gained — knowledge, technology and jobs– but troubles with communication made the fluid speech of close friendship difficult.

However, the community in Ben-Ayed’s classroom, he said, helped him and others, slowly overcome that language gap.

“Mrs. Ben-Ayed did something not anyone can do. She’s [tells] the students that you are safe, that you are good person, that you can speak,” Quedh said. “Never ‘You can’t;’ always ‘You can. You can. You can.’ And I study.”

Immigrant students in Ben-Ayed’s beginning ELL class have to learn quite a few things beyond the language, culture, jobs and etiquette.

They come to the United States to gain control and independence, but there is one thing they bring from their place of origin, Quedh said: a strong sense of brotherhood.

“I don’t care if I’m Jordanian or if I come from Iraq or if I come from Syria, because all of us, we have blood. We have meat. We have eyes,” Quedh said. “Why do I care this person is American, this person is Jordan?… I don’t care.”

By Adam Schoelz