Confinement

Juvenile arrests, detention change discipline mentalities

Sophomore Katie Neu wasn’t looking to get arrested. At the mall with a friend on a sunny day, she was looking to have a good time.

Sophomore Katie Neu wasn’t looking to get arrested. At the mall with a friend on a sunny day, she was looking to have a good time.

That’s why when the manager of the store ordered her and her friend to the back to empty out their bags, revealing the ill-gotten gains therein, Neu said things quickly went downhill.

“When it came to clothes, there was some stuff we wanted that we couldn’t afford, so we took it and stuck it in our bags. And then we actually went to quite a few stores — probably shouldn’t have done that,” Neu said. “The manager came over when we were leaving the store and said we had to go the back and empty out our bags, and then she found out and said, ‘Oh, you’ve been stealing from other people, too. What joy.’”

Neu and her friend are among the 10 million caught shoplifting annually, according to the National Association for Shoplifting Prevention. Neu said shoplifting was attractive and easy as well as a relatively low risk way of scoring some expensive items.

“It’s like that adrenaline rush where you really don’t think it’s going to happen to you,” Neu said. “You never hear in the paper ‘Teen girl steals clothes,’ but you hear about big wrecks and stuff, not the mall.”

After they had caught the girls, the managers called the police, and Neu found herself, for the first — and only — time in her life climbing into the back of a police cruiser.

“The only thing I was worried about was my parents, my dad especially,” Neu said. “I was really scared. Anything could’ve happened that would have made me feel better, but they called my parents.”

While Neu and her friend were waiting for their parents, the police left them in a small cubicle in the police station. The isolation, Neu said, caused her mind to run wild with frightening possibilities.

“It was really scary because all you want to do is get up and leave and act like it never happened, but they just kept on coming back and making you feel worse and talk about it,” Neu said. “It makes you feel really heavy, and you’re just like, ‘I don’t know why I did this,’ and you kind of see all the things you think are going to happen to you come through your mind.”

School Resource Officer Keisha Edwards said cases like Neu’s are important as watershed moments in a juvenile crime career. Going to jail for an afternoon and separating themselves from friends and family, she said, can stop shoplifters before they move on to more serious crimes.

“I hope that it is a scared straight moment, the isolation away from society,” Edwards said. “Too often, kids start with shoplifting and then move up to assaults, and then move up to drugs, and then move up to burglaries, and it becomes a combination of all, when it could have been stopped at that scared straight moment.”

While Neu may have spent an afternoon at the police station, Edwards said putting juveniles away is definitely not the first course of action for law enforcement. Juvenile detention is a last resort of sorts, she said, where the police send kids who need structured reform. A point system, similar to the driver’s license point system, dictates what happens when a kid commits a crime, she said.

“Everything counts. Referrals to the juvenile office for any offense, so that could be juvenile delinquency; not obeying parents, leaving the house without permission — those sorts of things all count for one point, and if you are arrested for a crime, a misdemeanor, it counts for two or three points, and if you are arrested for a felony it counts for four or five points. And so that total has to equal up to 15 before it’s determined if you get detained,” Edwards said. “They want to be able to be consistent with the people they are detaining, and they don’t want to base it on gender, race, or any of those things. They want to base it on the severity of what’s been going on with the kid.”

The adult world is different. Physical confinement is the most common way to deprive adult lawbreakers of their rights, with almost one and a half million Americans held as prisoners of the state, according to the Pew Center on the States.

Junior Jackson Harris*, who went to juvenile detention, got a taste of what time is like in jail.

“You don’t really keep track of days. That just gets tough,” Harris said. “You don’t want to know how much is in front of you, just got to go with it, like you don’t know what’s happening. It goes faster that way.”

Harris spent a month and 14 days in juvenile detention. That time, he said, was characterized by much time spent staring at walls and little formal education. Ironically, he said despite the lack of schooling, he found himself reading more.

“I read a lot because you’re not really thinking about time, and you’re reading, and you’re in your own head, and you’re not like looking around seeing the same thing that you’ve been looking at for the past 10 hours.” Harris said. The detention center “gives you a fifth grade curriculum, like courses that somewhat correspond to what you’re doing because it’s all fifth grade — that’s what it averages out to, the age that comes in there.”

While youths commit fewer than 15 percent of crimes, up to one-fifth placed in front of a judge will find their way into a detention facility, according to the Campaign for Youth Justice. Harris said the beginning of detention was the hardest because of the unfamiliarity of juvenile detention and the uncertainty of his future.

“The first 24 [hours] are bad because you just sit in a white room and lay down on your mat and look at the wall, and everything’s kind of hitting you at once because it’s the first time you’ve been arrested, and you don’t really know what’s going on, and you’re getting weird phone calls and weird people are coming by to talk to you or you’re having people come and get fingerprints.” Harris said. “You make friends. You usually make friends on detention side because you just sit there and talk to them, and you don’t have a lot of school … because you might be in there two days, you might be in there a week, you might be in there two weeks, you might be in there six months.”

On the other side of the law, Edwards is trying her best to keep students out of juvenile detention. While she recognizes that the detention system serves its purpose, she believes that the most effective strategy to keep kids on track by connecting community, school and police in a meaningful way. It is her job, she said, to make sure kids both understand the police and feel comfortable approaching them, so they can avoid losing their rights and going to jail.

“Not every officer can be a school resource officer. You have to have a lot of patience, and you have to have the ability to want to relate to the kids because it is a balance between police and community and bringing those two things together,” Edwards said. “I enjoy talking to kids about the law or giving interviews about the law enforcement world because a lot of these young kids don’t know about the law enforcement world and many of them are very curious.”

For Harris detention is now a distant memory, a bad dream. When he was inside, his freedoms were restricted and life a curious combination of uncertainty and monotony. Looking back, he said it seemed evident there was only one way out.

“They tell you what to do, and you can’t really question that,” Harris said. “I mean, you can, but you’d just be immature and self-destructive. It’s all about just playing their game.”

By Adam Schoelz

*name withheld upon request

additional reporting by Jackie Nichols

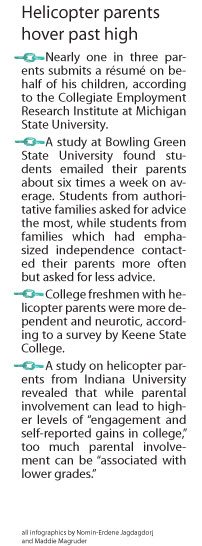

Over-parenting impacts individuality

As junior Abby Hake left her house to go to school, she shouted, ‘See you later, Mom’ before walking to her car. When pulling up to RBHS, Hake said her mother was not on her mind.

As junior Abby Hake left her house to go to school, she shouted, ‘See you later, Mom’ before walking to her car. When pulling up to RBHS, Hake said her mother was not on her mind.

During first and second hour, Hake focused on taking notes and studying for a chemistry test. However, by lunchtime, Hake’s attitude quickly went from content to frustrated.

In the hallway, she spotted her mother, the last person she expected to see during her school day. Because of her involvement in the Bruin Cup committee, PTSA and ‘For the Love of the Game,’ Hake’s mom is often at RBHS.

“My mom is incredibly involved with everything, so sometimes I’ll be walking through the hall, and I see her doing little errands around school,” Hake said. “I think she’s trying to relive her glory days, and sometimes I have to tell her to stop interfering in my life at school so much.”

Even though Hake worries her mom is too involved, Kay Hake disagrees. Her help is directed more at the teachers than her daughter.

“I help out at Rock Bridge because I believe the teachers are overworked and underpaid,” Kay said. “I think it affected [Abby] more at the junior high level because in junior high everything embarrasses you a little more. Once she got a little older then she learned that I was just helping out and doing it for her own good.”

Just as Abby wants to separate life between her mother and herself, associate professor of sociology at the University of Missouri-Columbia Wayne Brekhus agrees it is important for teenagers to develop on their own.

“Anecdotally, I see [the parents’] effects as negative because they don’t allow their teenagers to learn and develop important skills on their own, and they bail them out of consequences so that they don’t have to learn fully from their mistakes,” Brekhus said. “The even bigger effect is that over- parented teenagers often don’t take responsibility for everyday tasks — balancing budgets, handling problems themselves — because they know Mom or Dad will do it for them.”

Despite the possible negative outcome, senior Sami Johnson does not see anything wrong with the close relationship she shares with her parents. As an only child, Johnson is used to her parents being occupied with her life more than their own.

“I think my mom lives for my life. She loves to hear about all the drama and events that goes on in my friend group,” Johnson said. “It always gives me someone to talk to, so I definitely don’t see it as a bad thing. Sometimes she thinks my friends are more of her friends, but she makes my life a lot easier because she is always there to help me and give me advice.”

Although Johnson is used to her parents doing a lot for her, she feels their bond has not lessened her ability to make decisions and take responsibility for herself.

“I still function like someone whose parents aren’t as involved,” Johnson said. “It’s just nice to know that I have two people in my life who can help me make decisions if I need them. Both of my parents can tell when I need help, and I’m appreciative of that. Like last year when I had cheer tryouts then my mom could tell I was really nervous, so she helped me practice and helped me get it together.”

Unlike Johnson, junior Duyen Tran is used to her parents overstepping their bounds. Because of their Vietnamese background, Tran’s parents have struggled to find a balance between their traditional culture and the American way of life.

“Until I was about 15, my parents wouldn’t let me have sleepovers. They’re OK with people coming over to our house, but usually they wouldn’t let me go over to friends’ houses,” Tran said. “It’s something about purity, and since I’m a girl then I’m not supposed to go over to other people’s houses.”

Though her parents have been restrictive, Tran has noticed them relax more with time. According to www.miller-mccune.com, 60 percent of Asian-American parents teach their preschoolers reading and writing because they see their children as “seedlings that need help growing.” Although it is still difficult for her to make plans, Tran has a better grasp on their parenting style than she did when she was younger.

“I didn’t understand why they wouldn’t let me go to friends’ houses because I grew up in America, so I saw all my friends going to sleepovers,” Tran said. “My friends were inviting me over for stuff, and I didn’t get why I couldn’t. I would question their reasoning and motives, but now that I’m growing and they’re adapting to society more, I think they figured they couldn’t be so old-school anymore.”

Because of the advancing society, Brekhus relates the main problem with over-parenting to technology. Texting has allowed parents and their children to keep in touch even when they are not together.

“I think helicopter parents are far more common today. Technology makes 24/7 availability a real possibility, and it means that parents really can hover over their teenagers constantly,” Brekhus said. “When I was a teenager, you told your parents where you were going, when you’d be back, and if you were going to be late you had to find a payphone and call them.”

While the use of cell phones can be negative, Johnson’s viewpoints differ from Brekhus’. In case Johnson faces a difficult situation, her parents are just a few moments away.

“My mom and my dad both text me a lot throughout the day to see what I’m doing later and stuff like that,” Johnson said. “It’s good because I know that my parents are there for me regardless of whether I’m with them or not.”

By Maddie Davis

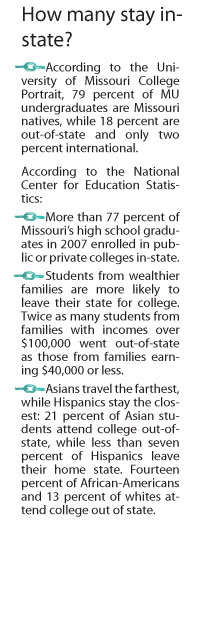

College expands horizons; Columbia offers familiarity

While some seniors prepare to leave the nest and begin the rest of their lives, others will remain here for the next four years. Those students will have to find a way to break out of the trapped feeling staying in the same place can create, the same feeling some of their peers are so desperate to escape.

Guidance counselor Rachel Reed said for many of her students, staying in Columbia after high school is easy because of the familiarity with the University of Missouri-Columbia and the low cost of an in-state school. She said MU can be a great place for RBHS graduates, but they should be careful that the University does not just become an extension of high school and that it has the majors and programs they are interested in. She said MU can become a fallback option rather than where someone actually belongs.

“For some students, they go to MU. They take advantage of not spending the money to stay in the dorms, so they live at home,” Reed said. “They choose classes that they know people from Rock Bridge who are going or from Hickman High School that are going to take the same classes, so I think it can be very easy to stay in the same friend circles and stay basically in high school even though you’re going to MU.”

But senior David Morris does not believe MU will be restrictive. He said the safety net Columbia provides is a good thing. Having family living nearby and already knowing his way around town will provide more benefits to him than limitations, he said.

“You’re really close to your family. If you need money or you forgot something you can go get it,” Morris said. “College is what you make of it. If you go in with  an open mind, then that’s what you’re going to get. You’re not going to be limited.”

an open mind, then that’s what you’re going to get. You’re not going to be limited.”

However, Morris acknowledges he will miss out on adjusting to a new place in a controlled environment such as a college campus. Instead, he won’t experience this until after college if he gets a job outside Columbia. In addition to this, he will have to live on his own, with no safety net.

Developmental psychologist Nicole Campione-Barr said adolescents who move away for college must acquire skills such as time management and self-care for complete self-reliance more than those who stay close to home. However, she also said students far away from home are more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as drug and alcohol use.

“While they might not be getting into as much potential trouble as their counterparts,” Campione-Barr said, “they are also not forced to take as much responsibility for themselves, nor are they engaging in a greater diversity of experiences from what they have encountered so far in life.”

Morris does not foresee limitations in the next four years, but when he does end up leaving, he expects only minor consequences from being in Columbia for so long. He expects college will allow him to see a new side of Columbia he has not experienced before.

While Reed, who attended MU and lived at home, said this is possible, she said the most important thing for Columbia students going to MU was to get involved in extracurricular activities. She said MU can otherwise become a confining school that offers few new opportunities.

“There are some student[s], though, who I’ve seen go to MU and completely make it their own experience,” Reed said. “Even if [they] live at home they’ve gotten really involved in organizations on campus, and they’ve made new friends, and they’ve found new passions, and they’ve really matured and grown up and have branched out from just the typical high school life.”

For senior Emily Smith, leaving Columbia was a top factor in her college decision. She will be attending the University of Tulsa, which is a six-hour drive from Columbia. Going to MU was never an option for her.

“My entire life I’ve known that I wasn’t allowed to go to MU because my parents wanted me to try something new,” Smith said. “They didn’t want me to always be in Columbia my entire life, and that’s something I grew up being told, so it’s something I wanted for myself as well. I knew that I wanted to be someplace new and not just depend on my friends from high school.”

Because Smith didn’t want to go to college with people she knew, she decided to go out of state. However, she believes not knowing anyone will be the toughest part for her to get used to at the beginning of next fall.

“It will be weird that other people will know people and I won’t,” Smith said, “but that’s part of the reason that I [chose Tulsa] because I want that challenge to try something new, and I want to be out of my comfort zone because I think that’s what college is about.”

Campione-Barr said one of the most important aspects of the college experience for adolescents is being exposed to new ideas. The skills that college students learn adjusting to a new place and making completely new friends will be needed later in life.

“College often exposes emerging adults to many new people from a diverse variety of backgrounds and learning to socialize with a broader social circle will be helpful for making new, important friendships,” Campione-Barr said. “But [it] also will help them learn to work with people from diverse backgrounds later in adult contexts such as careers.”

Smith is most excited about the opportunity to meet others, which she thinks will allow her to see the world with fresh eyes that staying in Columbia could not offer.

“I’ll have to get used to new perspectives and new people,” Smith said. “I think it will force me to be open-minded because not everybody loves Mizzou, and not everybody’s from Columbia, Mo., and not everybody has gone to school with me my entire life. It’s beneficial for me to meet all types of different people, so it will just be exciting.”

By Thomas Jamison-Lucy