When a shooting occurs within spitting distance of a school, one would expect the administration to respond swiftly.

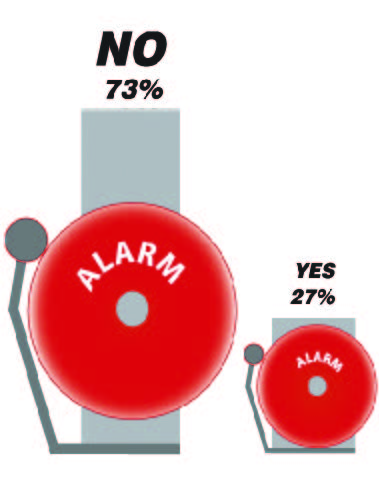

At RBHS administrators attempted to initiate a “code yellow” lock down.

But poor notification procedures caused the lock down to be less effective than it should have been.

The administration sent a three-sentence email that gave a brief description of the events to teachers and stated the school was under external lock down; teachers were to keep students out of the halls if possible.

However, without having told the teachers to be alert to the message, administrators assumed they would check their emails, a task many do not have time for during a typical class period.

The result: too many students ambled through the hallways despite the potential danger.

Across the parking lot, the Columbia Area Career Center instituted a similar lock down using email notification. However, administrators there told teachers over the intercom to check their emails, informing all teachers of the situation.

In contrast, some teachers at RBHS were unaware of the lock down.

Lack of proper notification during shootings on or near campuses has had tragic consequences. In 2007 administrators at Virginia Tech waited two hours before notifying students and faculty of an on-campus shooting via email; 20 minutes after the notification, gunman Seung-Hui Cho opened fire in classrooms, killing 30 more people. The Virginia Tech administrators could have saved lives by notifying students of the danger earlier.

A shooting occurred a few seconds’ drive from RBHS. Meanwhile, too many students wandered the halls during lunch, Alternate Unassigned Time and fourth hour classes. It is fortunate that the failure to properly notify teachers of the situation did not end in disaster, as the gunman could have been inside RBHS before the initiation of the lock down.

RBHS’s response went against proper external lock down protocol, as dictated by the RBHS emergency management manual. According to the manual, administrators need to announce external lock downs to teachers and students via an announcement over the intercom. Under “code yellow” protocol, classroom activities and instruction will proceed as usual.

Protocol exists for a reason. The incident that occurred on Providence constituted an external threat; let us hope we never face such a situation again, but if we do, administrators must follow the letter, as well as the intent, of the procedure.

Not notifying teachers or students of a lock down doesn’t just defeat the purpose of the procedure but places the lives of those within the building in danger. In all future events, administrators must follow procedure to ensure the safety of the school.

By The Rock