K-Pop industry abuses capitalist practices

March 7, 2022

Content Warning: mentions of anti-Blackness, sexual assault, restrictive diets, homophobia

Korean pop (K-Pop) has seen a steady rise in popularity, becoming a recognized global phenomenon in the past five to ten years and breaking into the Billboard Hot 100 chart at least eight times since the Wonder Girls became the first K-Pop group to enter the chart in 2009 with the English version of their hit song “Nobody.” According to an article from Mililani Times titled “The Rising Popularity of K-Pop” by Ellie Kim, streaming platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music have witnessed around a 65% and 86% increase in K-Pop listeners per year, respectively. In the face of K-Pop’s growth in popularity, it is critical to critique it as a market under capitalism and recognize the commodification of people within the industry, as well as how it reproduces existing marginalization against queer people, women and femmes and the Black community.

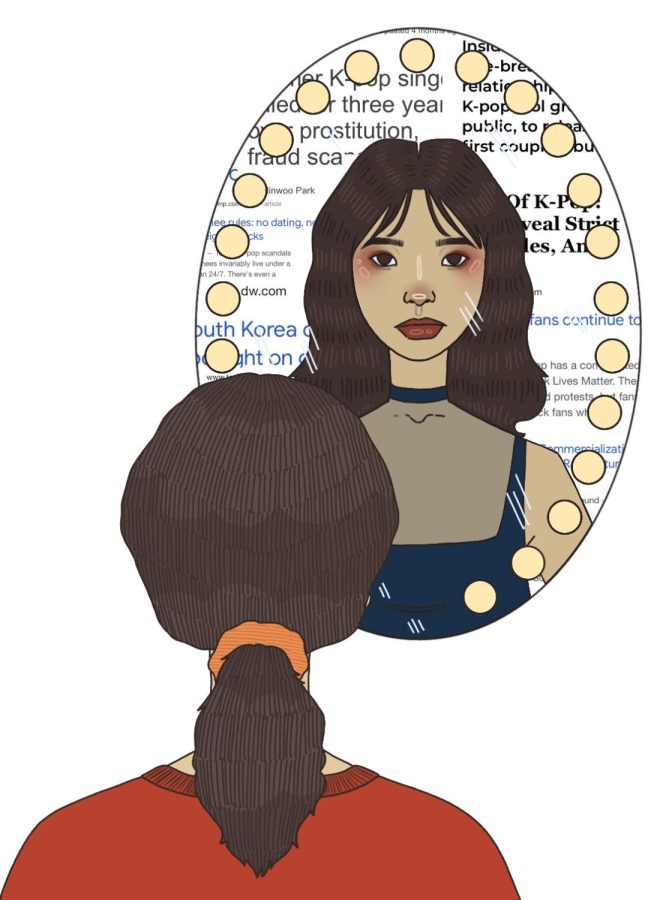

The lack of artists’ agency remains a structural problem in music industries around the world. Exploitation is found throughout idols’ careers in the form of slave contracts. These contracts are a manipulative practice that lasts an average of seven years in which bands only receive 10-20% of their earnings made from album sales, performances and promotional activities, while the management and the record label split the rest. The Korean male pop duo, TVXQ, sued SM Entertainment, one of South Korea’s largest entertainment companies, over a clause in their contract that outlined the company would not compensate the artists at all if their album sales did not exceed 500,000 copies. K-Pop idols are talent-scouted in their pre-teen years, and are inducted into a grueling trainee process where they are shaped into products for consumption. This process includes restrictive, unhealthy diets on top of hours of repertoire in singing, dancing and/or rapping. Momo, the main dancer for the K-Pop girl group Twice, shared how JYP Entertainment restricted her to only eating ice cubes in order to lose seven kilograms in ten days to fit the company’s weight requirement for debuting in a livestream with fans on the platform V-Live. This practice further reinforces the dehumanizing nature of capitalism in the form of problematic beauty standards. The K-Pop industry focuses on disciplining idols’ bodies through rigorous training, surveillance and regulation so that they become products that are accessible to any general audience of fans with the interest of pulling as much profit as possible from consumers.

The K-Pop industry heavily profits off of queerbaiting, which BBC defines as “the practice of using hints of sexual ambiguity to tease an audience,” in the form of homo-romantic fanservice that differs from non-promotional physical affection known as “skinship” by idols. This marketing strategy is not unique to K-Pop and can be found in popular Western media such as Riverdale, Supernatural, and Star Wars that have hinted at LGBTQ+ relationships between characters in the past to attract and profit off queer people and allies, but have done so without representing them fully to simultaneously pander to their homophobic audiences. Although it is hard to tell the difference between natural skinship and curated fanservice in many cases, there are still instances of queerbaiting in K-Pop that specifically stand out as problematic. In reality television shows, where K-Pop groups engage in various challenges to promote their music, there has been a series of problematic games. One, called the “paper kissing game,” in which a piece of paper is passed mouth to mouth sometimes results in unintentional kisses between players. These seemingly harmless challenges have transformed same-sex intimacy into a feature of entertainment that lacks genuine allyship against the systemic oppression queer people face.

Holland, the first openly gay K-Pop idol, made his independent debut in 2018. Multiple rejections from entertainment agencies on the basis of his sexuality forced Holland to crowdfund his debut album “Holland.” In a 2019 interview with The Korea Herald, he stated K-Pop often fantasizes about same-sex love in its marketing, while ironically remaining a taboo and sensitive subject in real life. This is a direct manifestation of capitalist conservatism, which exploits homo-romantic “fan service” to satisfy the fantasies of heterosexual fans without actually accepting gender and sexual minorities like Holland, who would usually have to hide their identity in the K-Pop industry to gain even a fraction of success. In his debut music video “Neverland,” Holland was featured kissing another man, which received a 19+ rating by regulators because it was deemed “unsuitable for young viewers.” When the kiss is performative for entertainment, it is acceptable for all ages, but when the kiss is one based on love and affection for someone of the same sex, people view it as inappropriate.The K-Pop industry is arguably a market under capitalism that aims to maximize profit, which is why problematic marketing techniques such as queerbaiting have surfaced.

The K-Pop industry as a market continues to generate profits by exploiting and undervaluing women, reproducing violence on a systemic scale toward female laborers. Members of girl groups experience the objectification of their bodies and little to no personal agency or bodily autonomy in their profession. Additionally, they face shortened careers due to social pressure to exit the workforce early. Rather than an individual crime, violence against female idols is a symptom of women’s subordinate position in an industry of male dominance. In the words of Bell Hooks in her book “Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics,” capitalism produces a culture of domination that attacks self-esteem, “replacing it with a notion that we derive our sense of being from one dominion over another.” Patriarchal masculinity teaches men in the K-Ppp industry that their sense of identity resides in their capacity to dominate female and femme workers which has resulted in the latter’s severe mistreatment.

In the process of objectifying human beings, the capitalist nature of the K-Pop industry commodifies other cultures as well, specifically Black culture, and continues to reproduce this exploitation through cultural appropriation and racism. “K-POP, Antiblackness, & Accountability, An Open Letter” by Anteeniya Bell describes how “anti-blackness is a tool of white supremacy, necessitating a lack of recognition in the humanity of Black people.” Anti-Blackness describes the ways in which non-Black individuals in the K-Pop industry preserve white supremacy. The K-Pop market takes heavy musical influences from R&B, Hip-Hop and rap music while simultaneously appropriating locs, cornrows and fashion popularized by the Black community, in music videos and performances. These instances of appropriation dismiss the work credited to actual Black creatives. According to an article from the Guardian, SM Entertainment did not give credit nor initial compensation to Black songwriter and producer Micah Powell for his self-produced song “Devil,” featured as the title track for the boy group Super Junior’s 2015 album. Lee Michelle, a Black and Korean singer, became known in the popular Korean singing competition “Kpop Star” for her powerful voice and performance. Despite her immense talent and versatility as both a rapper and singer, Lee Michelle has not garnered the popularity nor success of her colleagues, including Zico from Block B, Hwasa from Mamamoo, or RM from BTS, who have all appropriated and/or mocked Black culture in the past. The commodification of Black culture and the simultaneous elimination of actual Black people has exacerbated their dehumanization and perpetual ghosthood within the industry.

The K-Pop industry remains a system that inherently depends upon exploitation as a means of profit. Recognizing how music industries are inherently harmful towards people, identities and cultures, allows listeners to analyze the ways in which capitalism pervades various aspects of our lives. Listeners must shift their focus to the humanization of participants in the industry, idols and fans alike, within a larger struggle against capitalism which includes amplifying conversations that critique K-Pop and pushing for artists’ autonomy over their music.