In 2017, controversy broke out when directors cast Scarlett Johansson, a white actress, as Motoko Kusanagi, a character in the popular Japanese Manga series “Ghost in the Shell.”

This was not the first instance of whitewashing characters, and it wasn’t just the United States that was doing it.

In 2012, television gained its first ever series starring a South-Asian as its lead. Fox launched “The Mindy Project” starring Mindy Kaling. While Kaling was born in the United States, her parents are from India, and Kaling’s representation sparked a conversation about the racial representation in American shows and movies.

Decades earlier, in the ‘90s, ABC aired “All-American Girl,” a sitcom with Margaret Cho playing the lead. Even with other shows casting Asian characters such as “Star Trek” and “Mr. T and Tina,” the United States was still not ready to represent foreign cultures based on the public reaction. “All-American Girl” met its end a year after airing with only one season. Later Cho reflected back on her pain as she filmed the show. Cho was ‘too Asian’ and ‘not Asian enough’ at the same time.

In 1951, American television sported its first show with an Asian lead starring Anna May Wong. Wong was an activist against the whitewashing of television and the racial stereotypes that plague American media. She took the lead in “The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong,” a series following the life of Wong in a role as a detective written specifically for her. “The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong” aired on DuMont Network for 10 episodes before it was abruptly canceled.

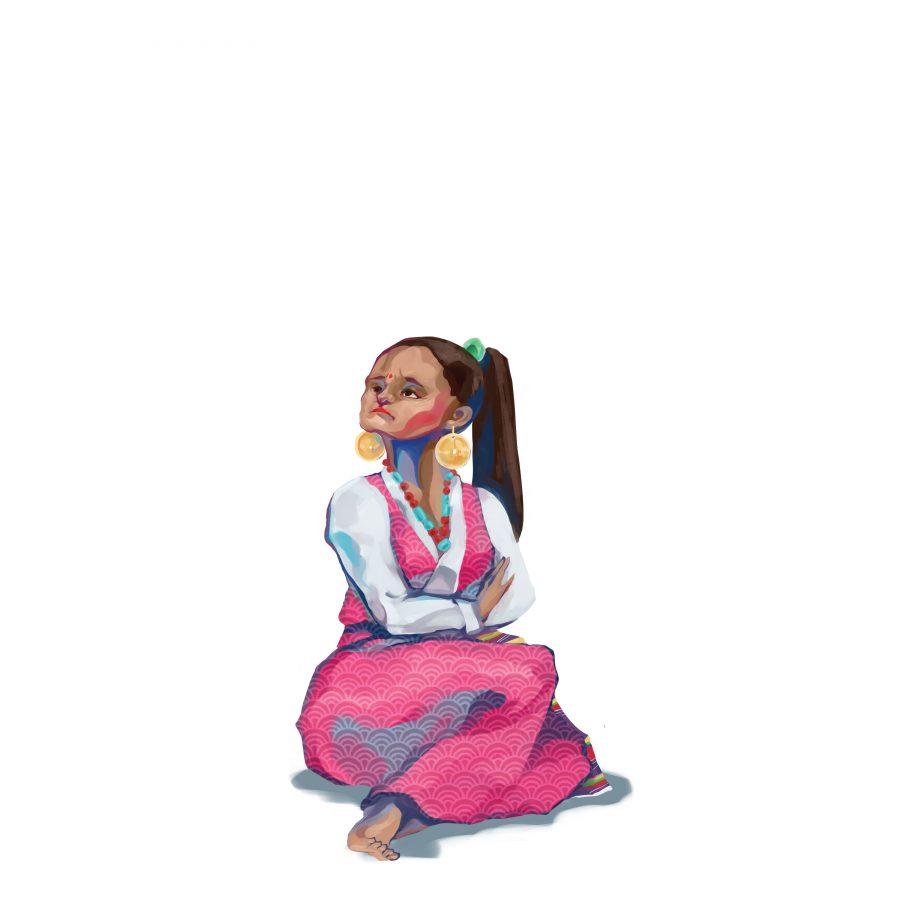

Halfway across the world, senior Anusha Mishra noticed the disregard of the color and culture of people in her own country.

“In Nepal, American people were regarded as prettier, so that was the beauty standard. I just saw that more around me [when I came to the U.S.]. It’s America, so there’s more white people,” Mishra said. “[In Nepal lots of white people were] on TV and in ads, and they usually photoshopped your skin to look whiter, and skin bleaching products were pretty much everywhere, and they wouldn’t even tell you sometimes.”

The growing market of skin bleaching products in India earns the industry more than $400 million annually according to an article by The Huffington Post. Despite the obvious favoritism for light colored skin in her home country, Mishra gained influence from television shows in which a girl that looked more like her was fawned over by men. Bollywood showed Mishra that Asians are beautiful as well, she said.

Even with this step forward, the actors and actresses were still much whiter than the average Indian citizen, and these eurocentric values guided viewers to see which Asians were considered pretty. In 2006, however, Mishra moved from the whitewashing of television in her own country to the reality of the white United States, with 77 percent of the total population being Caucasian, reported the United States Census.

“When I was [in Nepal], I’m actually like a pretty light-skinned Nepali person, so people used to compliment me a lot on that. That was something I actually took a lot of pride in,” Mishra said. “[When I came to the United States] I was obviously a lot darker than everyone else. All the pretty girls were the ones with blonde hair and light skin. And I wasn’t that, so I tried to hide the fact that I was Asian.”

For years, Mishra pushed against her own culture. She wouldn’t talk about her home country and didn’t correct people when they assumed she was native Indian.

Media, journalism and film professor Dr. Timothy White at Missouri State University recognized Mishra’s feelings of exclusion based on the cultural norm. When people don’t ‘fit in’ with everyone else, he said, they feel a strong need to minimize those differences.

“As a child, even bringing lunch from my own culture kind of like, terrified me because I was so afraid of people judging me because I didn’t have like, Mac and Cheese or PB&J,” – Sarvika Mahto, junior

“Outside of the U.S., in many of the nations that are former colonies of Western powers, there has been a feeling among some that the dominant culture is ‘better’,” Dr. White said. “The fact that teachers in these nations have often been trained in schools run by, or at least influenced by, the colonizers has tended to perpetuate this belief; however, ethnic pride has been growing both here and abroad, and these cultures are beginning to value their own traditions and cultures.”

Before Mishra came to take pride in her own culture, she believed people thinking she was Indian was better than letting them know where she was actually from. Likewise, junior Sarvika Mahto felt shocked when she arrived at preschool and realized just how different she was from her peers. Mahto immigrated to the United States from Nepal when she was just nine months old, and she grew up in a classic Nepali, Indian household. Mahto’s parents prohibited her from having sleepovers and didn’t watch the same things other kids did, stringing her as an outcast.

“As a child, even bringing lunch from my own culture kind of like, terrified me because I was so afraid of people judging me because I didn’t have like, Mac and Cheese or PB&J,” Mahto said. “I had different food, and I was embarrassed by it. A lot of it at first was quite embarrassing like I didn’t want people to think I was different, then as I grew older I realized there’s nothing really wrong with me being from somewhere else and experiencing different things.

Growing up, however, Mahto realized there was something different about her. Instead of watching classic children’s TV shows like Caillou, Mahto watched PBS and other educational channels, as well as Nepali movies and songs.

“As I grew older, I did realize that as I started watching shows, something about them was different and I was too little to really hold a grasp on that,” Mahto said. “I think as I grew up I realized it was just because they had a different background and their parents were raised a different way than my parents were raised so [we had] different ideals.”

While Mahto was more sheltered from the mainstream press, the whitewashing of television was prominent in media. Dr. White cites the cause as the audience, who was primarily white, wanting to see well-known actors and actresses who more often than not turn out to be white. In more recent years, Dr. White said, the commentary on movies such as “Crazy Rich Asians” indicates the film was very empowering for its own audience.

“I’m sure it is the same for African-Americans, women, LGBTQ and other groups who have traditionally either not been represented at all, or represented as marginal characters, and often the source of ridicule [or comic relief] when they see positive representations of themselves in the media,” Dr. White said. “It is not the same, however, for Asians who actually live in Asia, as they don’t really see themselves as being that similar to these characters in Hollywood films, and are already accustomed to seeing Asians in their own films. For example, my Singaporean friends and relatives just wish they lived like the characters of Crazy Rich Asians.”

As both Mishra and Mahto grew older and became more comfortable with who they are and who represents them in the media, they began to share their cultures more. Mishra made several friends who were also from Nepal and by the seventh grade began sharing more and more about her home country.

Just as Mishra grew more comfortable with mentioning Nepal over time, American media also settled in to representing people of Asian descent though TV shows. ABC’s series “Fresh off the Boat” in 2015 starring Constance Wu, Randall Park and Eddie Huang introduced Americans to the lives of an immigrant family starting a business in Orlando and Master of None with Aziz Ansari as lead actor.

“I think [showing more cultures] is a really big step. I know for me and my friends, the other Nepali people that I know, we’re not East Asian but we were still really excited to see the movies and stuff because it’s still a really big step for representation,” Mishra said. “Even when there’s more African Americans on screen I get really excited because that’s a really big step, even though I’m not African American.”

“Even when there’s more African Americans on screen I get really excited because that’s a really big step, even though I’m not African American.”

The release of “Crazy Rich Asians” with an all-Asian cast and “To all the Boys I’ve Loved Before” with an Asian lead sparked gratitude with praises of finally bringing more Asian representation to the big screen. Though Mishra is not East Asian, she still gets excited because of the similarities between East and South Asian culture.

“It might seem unimportant for an Asian character to be in a movie since they’re not even real, but movies and other forms of entertainment have a huge impact on our lives,” Mishra said. “We look for ourselves in our friends and our family which is exactly what we do in movies. Without representation, you just feel like you’re being ignored. Representation has been getting better for Asians over the years but there is still a long way to go.”