When it comes to historic scandal, there are many common motifs that are impossible to ignore. However, when it comes to the type of scandal that belongs in 18th century gossip columns and not on Advanced Placement European History textbooks, the motif that reigns above all is adultery. Last week on Royal Tea we discussed the six wives of Henry VIII, a powerful ruler with a potent desire for both sons and women. On this edition of Royal Tea, we will juxtapose Henry VIII’s adulterous schemes, relationships and juicy tales with those of Catherine the Great of Russia. (Keep in mind than any ruler with an adjective famously attached to his or her name is often an extreme embodiment of the adjective. Sorry Henry, all you get are Roman numerals and a bad rep. for beheading queens.)

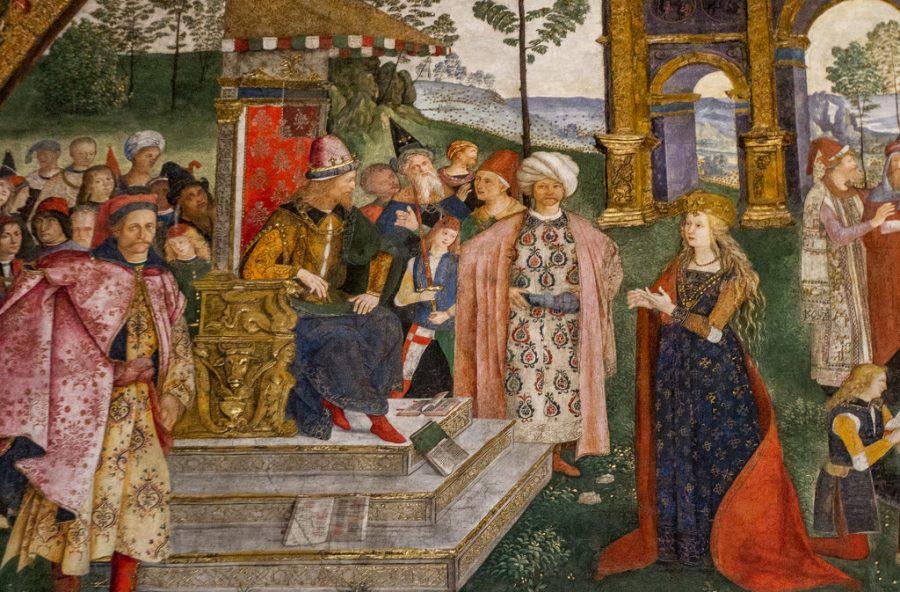

The road to Catherine’s “greatness” starts with the childless Empress Elizabeth, whose old age indicated that she needed to look for an heir. She picked her nephew, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp, a then 14-year-old boy who was neither physically talented nor intelligent. Immediately, Elizabeth began searching for a suitable bride who could not only neutralize Peter’s incompetence, but also produce her a grandson. She was quickly convinced by Joanna of Holstein-Gottorp, the sister of Elizabeth’s fiance (who tragically died before she could walk the altar), to betrothe the young Peter to her daughter, the future Catherine the Great, who was originally named Sophia Augusta Fredericka. After the death of her 12-year-old son, Joanna put all her efforts in Catherine’s upbringing despite being a cold and unaffectionate mother. The ambitious Joanna succeeded, and on Aug. 24, 1745, Sophia Augusta Fredericka, now converted to Orthodoxy and dubbed “Ekaterina” (Catherine), married Peter.

The imbalance of intelligence, beliefs were some of the many issues with the union of Catherine and Peter, alongside the fact that consummation did not occur in the marriage for several years. Fortunately, Catherine bore the opposite fate of her mother and gave birth to a son, Paul, whose paternity was rumored to belong to one of her many lovers, Sergei Saltykov. Catherine would even go as far as to credit the rumors that her son was not fathered by her husband, although it is likely that she only hinted of it to get a spite out of Peter. Although Peter was next in line for the throne, it was conspicuous that he was destined to become a poor and careless ruler who lacked the passion and vigor one needed to rule Russia. By contrast, the young Catherine the Great had worked diligently to dispose of all of her German roots and “Russianize” herself as much a possible, eventually becoming fluent in Russian and an avid promoter of Russian culture. Peter’s weak leadership skills were evident throughout his reign, which lasted a short period of six months. Throughout his rule, Peter showed a distaste for Russian culture, dressed up in the uniforms of Russian enemies, showed a profound preference for Prussia and supported the elimination of Orthodoxy from the Russian government. (Smart move Pete! Rule Russia and the Russian people by removing all things Russian. Besides, Russia is just one letter short of Prussia…) Catherine the Great aimed to take advantage of her popularity by gaining authority over her husband, and with the help of several co-conspirators, she arrested Peter on charges of conspiracy in July of 1762 . After Peter signed a document of abdication (not like he had a choice) Catherine took the title of empress regnant.

Catherine the Great’s great leadership, which stemmed from the fact that she was an avid listener and observer, went on to define the “Catherinian Era” — the Golden Age of the Russian Empire. Aside from her superb leadership and the prosperity that she brought to Russia, Catherine was famous for her long list of lovers…(just do NOT mention the rumor that her frequent trips to the stables resulted in inappropriate unions with horses.) Her unsatisfying relationship with Peter left her sexually and intellectually unstimulated, so she filled the void with a variety of young and handsome suitors, who were more than willing to keep Catherine company and remained loyal to her even after their passions subsided. Their loyalty likely had something to with the fact that Catherine was easily the #Sugar Momma of the century: her lovers received a variety of rewards during and after their relationships. One of her lovers, Pyotr Zavadovsky, got the rights to a pretty sum of 50,000 rubles, a 5,000 ruble pension and 4,000 Ukrainian serfs (get you an ex like Catherine the Great!). Before Catherine took the throne, she learned from Empress Elizabeth that the term “favorite” described the official lover of the Empress. Catherine had three lovers before she became empress, one of which carried on to her reign, but the majority of her lovers came after she overthrew her husband and gained access to the throne. Her ‘favorites’ were often selected or recommended by her past lovers, and many of them shared one trait: they were younger, sometimes much younger than she. She had genuine affections for at least five of all 12 of her lovers, but some of them she picked out and romanced on the fly simply to satisfy her sexual appetite. Catherine and her last ‘favorite,’ Platon Zubov, had an impressive 38 years between them, and, at 22, Zubov became one of the most influential men in the Russian Empire, gaining titles like Holy Roman Prince and Governor-General of New Russia. Catherine’s fondness for her lovers often sustained many of their sociopolitical stabilities, and her death in Nov. 17, 1796 was a problematic day for her favorites, like Zubov, who lost a large chunk of his prosperity following Catherine’s death.

Royal Tea: Catherine the Great

April 1, 2018

0

More to Discover