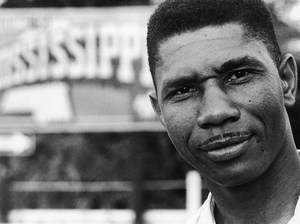

[dropcap style=”light” size=”4″]A[/dropcap]fter surviving three years of World War II, Medgar Evers had to face a more daunting challenge back home in the U.S. Born in Decatur, Mississippi on July 2, 1925, Evers joined Alcorn State University at age 23, and after graduation in 1952 he joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Before joining NAACP, the supreme court case of Brown v. Board of Education inspired Evers and he decided to quit his job in insurance business. Evers then applied to the University of Mississippi Law school, but the school did not accept him. Although the school denied him, Evers was given a different opportunity by the NAACP. The civil rights organization, who recognized his efforts, positioned Evers as the first state field secretary of the group in Mississippi.

Through this position Evers organized voter registration efforts, along with demonstrations and boycotts. One of the most memorable actions by Evers as field secretary was investigating the wrongful and racist crimes against black citizens. When 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched just for talking to a white woman, Evers took action

Evers along with co-workers Ruby Hurley and Amzie Moore were able to get witnesses to come forward and testify at the 1955 trial of the two men accused of the murder. Their work didn’t stop there; the NAACP members protected these witnesses who testified by getting them out of town in secrecy after the all white jury conferred after an hour that the men were not guilty.

Although Evers failed to integrate the University of Mississippi, he was one of the key players in getting James Meredith into the school. The desegregation was ruled by the Supreme Court in 1962 and Evers along with other NAACP members, accompanied Meredith to register for classes. This did not garner a positive response by the white community and in response to the growing mob, President John F. Kennedy had to send more than 30,000 National Guardsmen.

While Evers was successful, this natural phenomenon made him the target of hostility by white segregationists. Evers had to make a difficult decision when he decided to fight for African American civil rights. The hatred he got in response for his fight against discrimination put his wife, Myrlie Evers-Williams and their three children at risk.

This potential hazard ultimately led to Evers death when June 12, 1963, he was shot in the back in his driveway. While in the hospital, Evers was pronounced dead after less than an hour.

His death was met by national outrage which let to increased support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Responses included a demonstration and riot during the funeral; in an effort to stop the 5,000 mourners, the police violently clashed with the protestors.

It took 31 years to bring Evers murderer to justice. Byron De La Beckwith, a White Citizens Council member was arrested two weeks after the assassination. However, twice the all white jury found him not guilty. Up until the 1990s Beckwith was free, but when the widowed Williams found new evidence the case was reopened. On Feb. 1994, Beckwith was sentenced to life in prison by a racially mixed jury.

Evers legacy still lives on today as Williams was elected as a chairperson at NAACP and founded the Medgar Evers Institute in Jackson, Mississippi, where they strive to continue Evers’ work.

Take a look at the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute here

Sources:

http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/medgar-evers

http://www.history.com/news/7-things-you-should-know-about-medgar-evers

Categories:

Celebrating Medgar Evers

February 21, 2018

By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31653016

0

Tags: