In the midst of the growing racial tensions and violent prejudice of 20th century America, a young girl born to a middle-class family in New York City knew that she was destined to dance. From the age of five, ballet had fascinated Raven Wilkinson. Although it was rare and hardly acceptable for an African American woman to perform as a classical dancer during the early 1940’s, nine-year-old Wilkinson began to study under the direction of Madame Ludmilla Shollar, a well-known Russian ballerina.

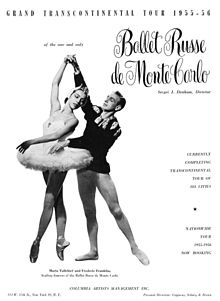

Wilkinson’s dedication and passion for performance drove her remarkable career that has helped to break the through segregation in classical dance. Determined to become a professional dancer, she auditioned with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1954. After two rejections, Sergei Denham, the company’s director, accepted her into the company and promoted her to a soloist in her second season. Wilkinson danced with the troupe for six years, earning major roles including a solo waltz in “Les Sylphides”.

Although Wilkinson’s talent was worthy of the position, her status as the first African American female ballerina touring with a major dance theatre put her and the entire company in jeopardy.

When we walked in, it was full of lovely couples, families with little children—a wonderful family atmosphere. Then, as I pulled out my chair, I realized that they all had Ku Klux Klan robes on the seats next to them. I remember thinking, here are people who can be so cruel and ugly, and yet they’re so loving toward their own families. In a way it made me less frightened of them. They lost some of their power in my eyes. – Raven Wilkinson to Pointe Magazine

Fellow dancers and directors told Wilkinson to cover herself in white makeup, stand with the foreign dancers, and claim that she was Spanish if ever questioned about the color of her skin. Contrary to her performance instincts, the societal conditions of pre-civil rights era America forced Wilkinson to blend in with the other dancers.

Wilkinson’s historic career was no stranger to racially charged hate speech. The company’s tour through the Jim Crow south pushed Wilkinson right into the face of hateful and violent racism. More than once, members of the Klu Klux Klan accosted and humiliated Wilkinson. In Montgomery, Alabama a Klansman stopped and boarded the touring bus, flinging dancers’ bags to the ground. Fearing for her safety, the company told Wilkinson that she could not perform. That night, locked up in her room, Wilkinson saw a burning cross from her window.

My never-ending question is: When are we going to get a swan queen of a darker hue? How long can we deny people that position? Do we feel aesthetically we can’t face it?- Raven Wilkinson to Pointe Magazine

Decades later, Wilkinson remains an advocate for diversity in the ballet industry and a mentor to a new generation of artists. Misty Copeland, a cultural icon and the first African American principal ballerina at the American Ballet Theatre, honors Wilkinson as her mentor and an inspiration in the face of adversity as a minority performer. Trailblazer: The Story of Ballerina Raven Wilkinson by Leda Schubert, follows Wilkinson’s historic career through her time with various companies around the world and closes with the scene of Copeland’s debut in “Swan Lake”– suggesting that Copeland will continue to open doors to diversity as Wilkinson once did.