For eras, artists have been revered for their classic styles, rich history, hidden morals and extensive collections of their artwork renowned by the world; all except for the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. Vermeer’s character as a whole is a mystery to this day. In 1653 he was accepted into a local Dutch painter’s guild at the age of 21 with little to no recorded previous training as an apprentice or student.

Vermeer, having only made 36 known paintings (perhaps even 45), was able to make way in an art-hungry society, where the best and most renowned Dutch artists turned out hundreds of pictures for the border market. It was as if a flush of talent suddenly bursted within Vermeer, allowing him to create uncannily realistic paintings and become a master in the field of chiaroscuro, light and shading effects in art.

However, recent developments may have uncovered the answers to this question. Art critics have begun believing Vermeer’s talent may have been aided with the use of a camera obscura — a black box with a lens mounted on one side that projects images proportionately onto a wall or screen — which further developed the vivid and saturated tones that have caught the eyes of many alike.

A quick analysis of Vermeer’s known artworks show an ongoing theme in domestic scenery. Most of his art shows little to no storyline or hidden plots — simply captures freeze frames of everyday life from his perspective. Although his earlier works may have revolved around subtle hints of religion and mythology, especially Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and Diana and her Companions, these references seem to be influences from earlier artist inspirations. His signature still-life style being developed and enhanced throughout the rest of his career as in the 1650’s with The Kitchen Maid.

The most notable feature of Vermeer’s work, however, is the lighting and sharp contrasts that enhance the realism of his portfolio and famous works such as Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Lacemaker and Girl with the Red Hat. His art constantly works with the saturation and optical effects of color, focus and the behavior of light. Certain areas of his work are blurred, while others are heavily detailed as if the raw image was witnessed through a lens — a quality not seen in most art that features most elements of the piece in full focus.

Vermeer, having a fairly blank resume to begin with, along with his play on focal points caught the interest of two onlookers in particular, London architecture professor Philip Steadman and artist David Hockney.

The two questioned Vermeer when scanning through his repertoire of impressive art, including little details such as shiny foreground highlights and slightly out of focus objects throughout. Their conclusion? A lens. Steadman and Hockney both published titles addressing their theories, Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth Behind the Masterpieces and Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of Old Masters, respectively. The art world, in response, was furious and major controversy was provoked, although more hatred was labeled towards Hockney for not accusing only Vermeer, but many other great 15th century painters for the secret use of lens-and-mirror inventions for photo-realistic effects.

Leading art historians have taken their own twist of the Hockney-Steadman babble. Some, like Walter Liedtke, have acknowledged the possible inspiration but detest the dependence the conspiracies place on the use of such contraptions. Furthermore, the validity of Hockney-Steadman accusations were seen as such — unproven and untested theories that were never experimented upon until the arrival of Tim Jenison, an inventor from San Antonio.

In 2001, nay-sayer James Elkins stated, “the optical procedures posited in Hockney’s book are all radically understated…no one, including myself, knows what it is really like to get inside a camera obscura and make a painting.” The notion of the use of a “camera obscura” — a lens projecting an image of one side of a room onto another surface equidistant on the other side— to paint a picture piqued the interest of Jenison, saying, “I had an epiphany — the photographic tone is what jumped out at me. Why was Vermeer so realistic? Because he got the [color] values right. Vermeer got it right in ways the eye couldn’t see. It looked to me like Vermeer was painting in a way that was impossible. I jumped into studying art.”

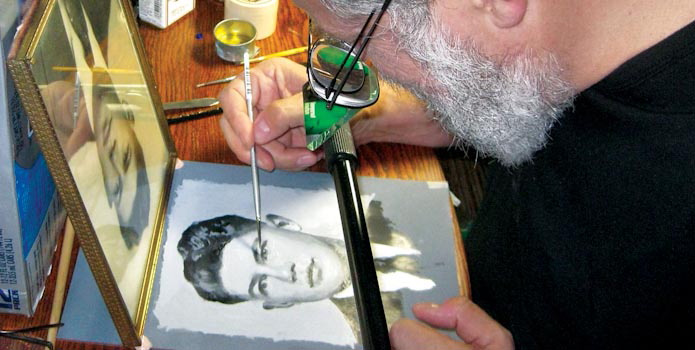

The painter would then be able to look back and forth between the copy and the bit of reflected image, the artist could then match the color and tone precisely by comparing the reflection in the mirror with the tone of his paint, “when the color is the same, the mirror edge disappears,” Jenison said. Slowly, the painter could illustrate broken sections of their work and piece together small areas until a full image was completed. Jenison, having no art experience whatsoever, decided to use himself as the test subject, a perfect and unseasoned beta tester. He first began with a small portrait of his father-in-law, ending with a near-perfect replication. This was tested again with a full color painting, and the same results persisted, proving the possibility of a possibly inexperienced painter, such as Vermeer, to be able to create dazzling works as he once did.

Jenison’s journey lasted years, and involved himself creating a 3D model of the featured room through computer graphics and even visiting the actual painting in Buckingham Palace. He furthered this obsession by fashioning and replicating the exact scene pictured, replicating the girl at the harpsichord, her male teacher by her side, the harpsichord and about every other aspect of the room by hand.

As if the challenge couldn’t get any harder, Jenison fashioned and mixed the paints himself and refused to work by artificial lights, using only natural sun. Jenison truly created a room reeking with Vermeer and the motivation of Jenison’s extensive conquest. Luckily, the inventor was rewarded with a satisfactory result.

Vermeer was widely recognized for his amazingly photo-realistic art full of vibrant glows and contrasting shadows that left viewers in awe. However, along with Vermeer’s controversial upbringings as an artist, recent years have also questioned the man’s raw talent in general through various conspiracies.

Although the validity of Vermeer’s talent is undoubted, the aid he may have possibly had has torn the art world in two with Steadman-Hockney theorists versus those with complete faith with Vermeer. However, the experiment presented by Jenison does raise the debate of if Vermeer was aided with a camera obscura, would his art be considered an old form of photography, or even traditional art as a whole? Although the experiment does not necessarily prove the Steadman-Hockney theories, the possibility has shown for itself to be present.

One thing that is certain is that the unfathomable realism of Vermeer’s art is definite, and whether or not he was aided in his artistic conquests his art will be considered undeniable arts in the development of realist history.