The United States is noted for its glitz and glam spanning from coast to coast in states such as New York and California, with little to be desired from the states in between. The Midwest, often known for its flat and grassy farmland, would be compared to the “armpits of America” without the bustle of fantastic cities left and right of it. However, this dinky part of America has been presented with redeeming qualities thanks to its portrayal by American artist Grant Wood.

Wood, who grew up in Iowa, could be defined as “a true patriot.” He grew up on a farm in Iowa and grew an immense admiration for the simplicity of the Midwest. His farm was full of life, and was where Woods owned his own goats, chickens, ducks and turkeys.

Sadly, though, his precious farm was sold after the death of his father, and his widowed mother could no longer support the farm on her own. The couple were relocated to Cedar Rapids, a city with far more hustle than their previous farmland. It was from there Wood began occupying himself in painting and the arts, taking art classes at school, teaching art, making jewelry, learning carpentry and decorating other people’s houses. Even after joining the army during World War I his job was to paint camouflage patterns onto tanks and cannons.

While on duty, an artistic shift happened within the American culture. Art students had been encouraged to study the styles of nineteenth century French Impressionists, and Wood followed suit.

In 1920, Grant travelled to Europe and studied the likes of Pierre Bonnard, Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro, but despite all efforts to recreate their works, his love of the Midwest reappeared, inventing a new style unique to Wood. Wood’s methods incorporate the sights and scenes from his midwestern childhood while applying aspects of European design into a mix of an impressionist Americana.

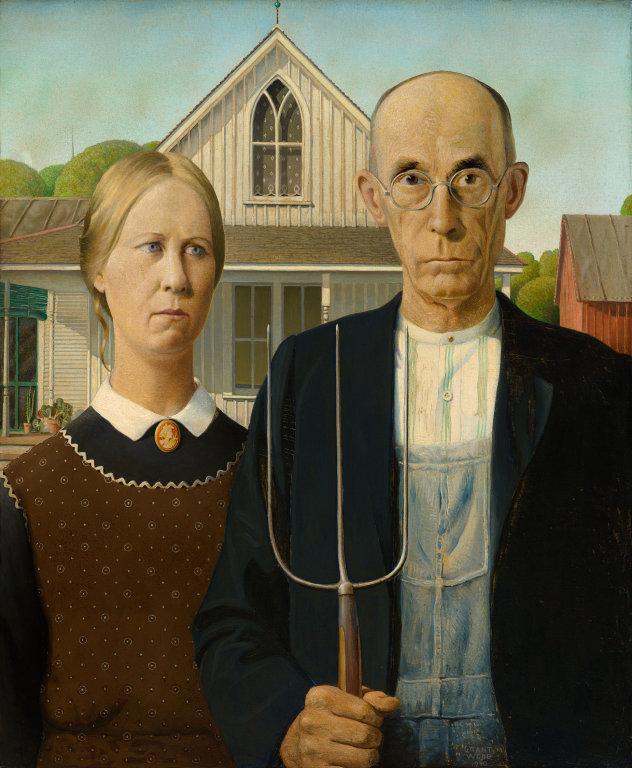

This new and iconic style can be seen in American Gothic, which Wood claims features an “affectionate portrait” of a man and his daughter by a house in the Midwest. The purpose of the picture was to be entered into the Art Institute of Chicago’s 43rd annual exhibition, and even earned a bronze medal and $300 prize. Afterwards, the painting gained great fame through widespread newspaper photographs, even becoming part of a series of patriotic posters, and being redistributed as a poster of the painting on a black background with a quote from president Abraham Lincoln plastered on top.

The title, American Gothic, is such because the the house was created with aspects of Middle Age Gothic architecture, primarily seen in the window that initially caught Wood’s eye. His art having been called “a perfect example of Midwestern steamboat Gothic architecture”, Wood enjoyed the contrast between the European window and an American farmhouse and placed the Gothic window promptly in the center background.

The window continues to play a primary part in the piece in regards to the total composition, specifically the symmetry and repeated patterns. The window features two equal arches capped to a point with a top pane that joins them together. The frame of the window is repeated several times throughout the painting, the pattern giving the composition a steady rhythm. The frame is duplicated with the addition of the father and his daughter, with their heads and stance reflecting the arches and the capped pane expressed in the background barn.

Furthermore, the arches reappear—although more subtle and upside-down—again in the repeating pattern down the stitches of the male figure’s bib, as well as in the prongs of the pitchfork (originally a rake) he holds. Although the significance of window are otherwise unknown, Wood’s artistic decisions of its subdued reappearances emphasize the impact the Gothic style to him, as well as in the fairly closed-off society of the Midwest.

Other small details include the minuscule plants peeking behind from the female’s left shoulder. Further analysis has concluded the plants on the porch are a geranium and a mother-in-law’s tongue (Sansevieria). Although no further description was provided from Wood himself, often plants provide deeper meanings into art, and these specimen are no different. Wanda Con, a primary scholar on Wood and his work, speculated the Sansevieria alluded to the hardiness of pioneer women, especially since it had been made popular to women in the Midwest due to its hardy nature. However, rather than conveying a hidden meaning, the plants seem to add more to the composition as well as Wood’s personal style.

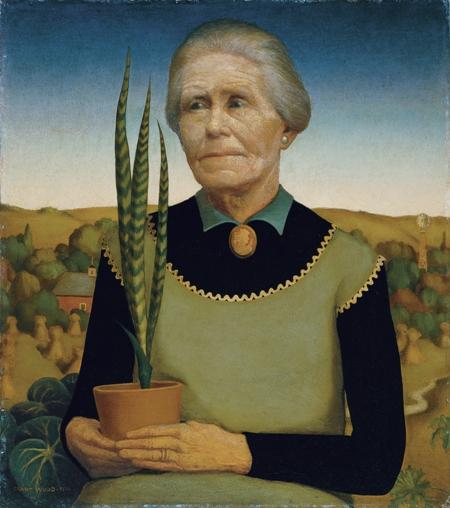

The geraniums reflect the “fairytale” trees in the far background and the mother-in-law’s tongue once again makes a small nod the the window and pitchfork. Although the largest contribution of the plants would be their reappearance in Wood’s other works, namely a 1929 portrait of his mother in Women with Plants. Wood’s mother’s portrait places Wood’s mother in front of another geranium, as well as the cotton-like trees once again. The mother holds a potted mother-in-law’s tongue in the foreground. The consistent art style and art subjects, ranging from family to landscape, have shined a light upon middle America and the nostalgic whimsy presented in the geography.

This bit of analysis, however, has yet to cover the two notable figures that take up two-thirds of the painting, the father and daughter. The daughter was based off of his sister, Nan, and the father off the family dentist. In addition to the two’s odd background story, despite Wood’s claims of affection, the duo seem anything but, and would better be described as aloof. This strange ambiguity initially lead to the consensus, that the painting had a purely satirical purpose meant to intrigue the human mind about the midwestern life. When the painting first became famous Wood attempted to clarify his intentions, saying, “I do not claim the two people painted are farmers. I hate to be misunderstood as I am a loyal Iowan and love my native state.”

Many viewers began creating their own fanciful stories and background speculation, a property Wood even teased shortly before his tragic death in 1942, teasing, “Papa runs the local bank, or perhaps the lumber yard. He is prominent in the church and possibly preaches occasionally.” People have even created their own renditions or comparing the couple parodies of famous duos from Ken and Barbie to Mickey and Minnie Mouse, to even a political comment on presidential lines with their first ladies.

This supposed comment, other midwestern landscapes and historical scenes even led to Wood becoming a spokesperson for the American Regionalist Movement. However, not all were pleased with such cryptic explanations. At first sight people either loved the painting or hated it, a fifty-fifty chance. Some more negative responses were expressed by local Iowans, Wood’s local community, mainly from the odd interpretation of midwestern life. The New York Times finding “A local woman told Wood he should have his head bashed in; another threatened to bite off his ear. Non-Iowans, especially the Eastern elite, felt the painting was a perfect comment on what they took to be sour Midwestern narrowness.”

Whether or not Grant Wood painted a masterpiece or an offensive commentary of the Midwest, scholars have agreed upon that he allowed for the re-emergence of middle American beauty, but also started a conversation that brought prominence to the interpretation and execution of “modern art.” With influences of childlike whimsy, European impressionism, and of course Iowa, Grant has become a staple in patriotic artists, with his work American Gothic even being ranked alongside the likes of the flag, the eagle and the Statue of Liberty in terms of a recognizable national emblem influencing all.