[dropcap color=”#” bgcolor=”#” sradius=”0″]I[/dropcap]t’s 7:40 a.m. at Memorial Middle School in Joplin, Missouri; the year is 2006. A student has just fired a MAC-10 into the ceiling. Principal Stephen Gilbreth is on the phone with a parent when he hears the shot. He immediately goes out of his office and races down the hall to meet the shooter.

“I didn’t realize who I was confronting, but he had a hood pulled up over his head and a white T-shirt or some kind of white garment tied around his face so I could only see his eyes peering out of this,” Gilbreth said. “There was a hood pulled down over his head and so I’ve got to be honest that for a moment, there was an ‘Oh, crap’ moment when I got down to the end, and I was like, ‘Oh, my god, it’s just me and him and he’s got a gun.’”

Gilbreth had no way of knowing the assailant’s gun had actually jammed, nor did he know that the single gunshot had hit the cooling system of the school, releasing 380 gallons of cooling fluid from the ceiling. He only knew there were 700 other children needing protection.

“[We] had a fairly lengthy conversation with him about putting the gun down. Eventually I talked him into walking out with me,” Gilbreth said, “… I walked him out of the building, and about that time 30, 40 seconds after we got out the building, there were police coming down the street and they apprehended him next door in what was the old public library.”

It was finished as quickly as it started. The brevity of the attack is no surprise, considering most school shootings are concluded within seven minutes, according to Columbia Public Schools security director John White. But even with the shooting over and no one hurt, Gilbreth said a gash would stay open in the community for another two years.

School shootings are a new standard in American life. According to Everytown For Gun Safety, an anti-gun violence organization, 174 schools have experienced shootings since 2013. Media frenzies to cover it, and in Joplin nationwide press arrived before the school day was even concluded. While the country grapples with the stories put out by the press, school staff such as guidance counselor Dr. Samuel Martin are especially affected by the stories of violence in the places they spend their lives.

“It just breaks my heart because, I think for me, school should be a place where you’re safe, where students can thrive, where students feel a sense of belonging…,” Dr. Martin said. “I think about Sandy Hook where there’s a mass killing like that. That’s heartbreaking.”

Sandy Hook grabbed the nation’s attention by its particularly saddening victims. In December of 2012, 28 people, most of which elementary schoolers, were killed in their school. The tragedy struck a chord with many. America had witnessed school shootings, but none quite as devastating by way as the casualties. Even in 2016, people still recount the heartbreak in Sandy Hook.

[quote cite=”Dr. Samuel Martin”]It just breaks my heart because, I think for me, school should be a place where you’re safe, where students can thrive, where students feel a sense of belonging.[/quote] The whole world reacts to school shootings, but on its own the microcosm of Joplin buzzed with a myriad of emotions. Some community members gave love and support to MMS, others sent hatred and anger.

“I think most of it was, from the community anyway, huge support and an outpouring of gratitude. The folks that found fault with it, I don’t think they had a child in the school or even a child in the district,” Gilbreth said. “We live in a community of 50,000 people, so there’s bound to be somebody that you know is going to say something that’s inappropriate.”

While the districts where shootings have occurred takes the flack for these mistakes, other districts like CPS can learn from it.

“We literally look at each one of those and try to glean as much information as we can —what went wrong, what went right, where can we make changes,” White said. “What did the students do right? What did the staff do right? Did anybody do anything that we think we could do differently? So we learn from each one of those.”

The examination of other shootings caused RBHS’ use of the buzzer system and the ALICE plan, which stands for ‘Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate,’ to stop an active shooter. White admits with even all of this planning, the spontaneous nature of shootings make it hard to plan. White said that in a shooting, a student’s job is to keep themself safe.

Assistant Principal Dr. Tim Baker is supportive of the ALICE plan and is one of the district’s trainers for teaching the protocol. He praises the organization and logic that this system provides. He said that the previous system of sitting, waiting and locking down was unsafe because it still kept students near the shooter.

“Before it was like all 30 buildings were doing their own things, and that’s scary. If we don’t know how we’re doing to respond. When everybody does it differently it’s more scary than anything,”Dr. Baker said. “Now we’ve got a fairly consistent response from building to building.”

This protocol is not for an “if” but for a “when.” RBHS is no stranger to shooting. In Nov. 2011, suspects fired shots in front of the school on South Providence Road. A stray bullet hit a car, but no one sustained an injury and the school locked down. Police apprehended the shooters. While that altercation was resolved with little issue, there is always the threat of another shooting. Beyond the preventative security measures taken by CPS, there are resources aimed at stopping the shooters before they get a gun.

“We have a pretty good service for referring students that teachers have talked about,” Dr. Martin said. “We have multiple eyes on students so it’s not just their biology teacher that’s watching them. It’s everybody, a team, a village.”

While White asserts that students should not be preoccupied with fear, he said they are the most important piece in the puzzle to prevent school shootings. White said most shooters tell a friend their plan in advance, and reporting those intentions can stop a shooting.

“If you see or hear something, you need to tell somebody,” White said. “[School shooters] have sent clues out or have given clues to the people who are close to them that they were thinking about doing something like this or had the potential to do something like that. So I would say that is probably the biggest impediment because it comes as a shock but yet somebody knew about it.”

Students are not only what can stop a shooting, but they are what remedies it after the fact. Gilbreth described a sense of unity shared by the students after the shooting. He believes that going through this experience proved to the children how strong they and their faculty are.

“The kids were incredible. There was almost a sense of taking care of each other for at least the rest of that year, and I noticed quite a difference for even into the next year because at the time there were 750 kids at this school and for Joplin, that’s a big school,” Gilbreth said. “We had a free and reduced rate of 54 percent, so there’s a lot in terms of socioeconomic [inequalities]. There was a great deal of poverty in this school and they felt a sense of, ‘Hey, we’re a part of MMS.’”

After the camera crews moved away and the initial shock subsided, some stains couldn’t be washed from consciousness. At the end of the year, a teacher from the school retired because of daily stress headaches. Gilbreth himself is reminded of his scrape with gun violence every time he hears about it on the news, and the stench of gunpowder fills his nose as freshly as the day his student fired when a school shooting appears in the media.

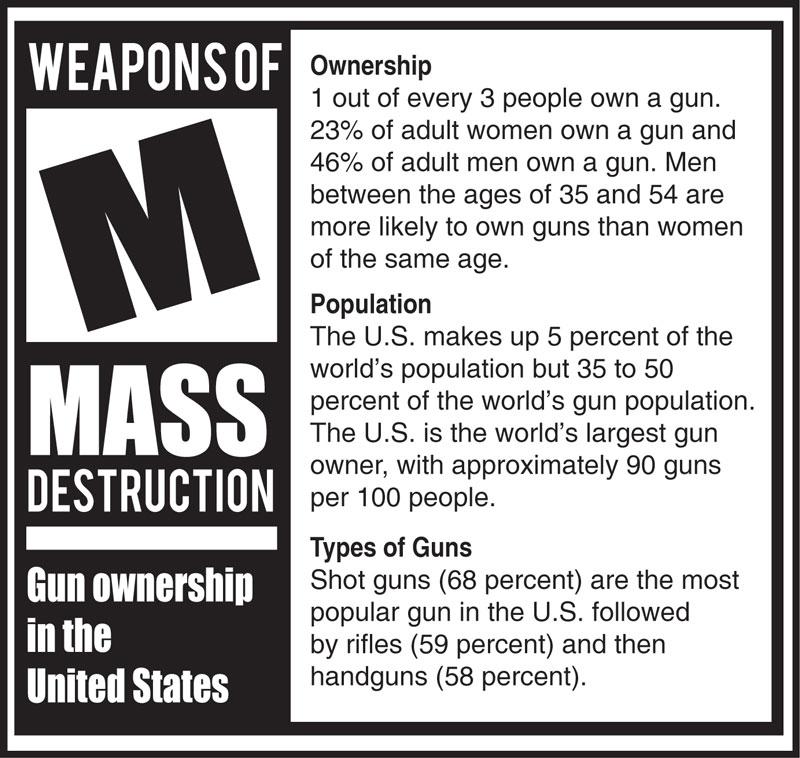

Shootings usually leave behind a discussion on highly politicized issues such as gun control or mental health. Politicians have been using this as a reason to tighten gun control. After the Sandy Hook shooting, the state of Connecticut banned high capacity magazines and also broadened the preexisting automatic weapons ban. Shootings have also caused an outcry for mental health. What is seen when poor mental health is armed has made many people wary to grant access to arms to mentally ill individuals.

“I know it’s been happening more frequently than it hasn’t been. There’s been a lot of stuff in the news, and it stays in the news for a long time,” junior Morgan Kruse said. “I also believe that whoever goes in there was not in their right mind, be it a student, a parent or a teacher but I think it goes a little above and beyond sometimes what it needs to.”

As more shootings occur, others are left as just statistics or proof in a debate. In other schools, it serves to break teachers’ hearts and to prepare all in the district to be safe in case the unthinkable does happen.

In the schools where shootings transpire, the coverage that allows others to react is just the second set of hurdles before the ordeal can be over. Gilbreth believes the country needs to reexamine its use of social media surrounding these tragedies. In the brilliance of hindsight, many blamed the administration, speculates Gilbreth. Some community members believed if the school had stopped the shooter at some point in his life, this wouldn’t have happened.

“People need to understand that teachers and folks that are a part of schools really do come to school everyday with pure motives to make a difference in a child’s life,” Gilbreth said, “When something so devastating happens it makes it difficult for everybody to understand it.”

Do you feel that RBHS is prepared in the event of a school shooting?