Translate

In the finale of the 2015 Eurovision Song Contest, the judges named Conchita Wurst, a transsexual from Austria as the winner. She not only became a source of pride for Austria, but also for the transgender/transsexual community on account of being the first trans individual to win Eurovision.

First broadcasted in 1956, the Eurovision Song Contest is a television show that showcases talented singers across Europe with a record of 43 countries participating in 2008 and 2011. Each country sends one singer or one band to participate, and in the final round, all the countries vote to determine the winner, one of the more notable winners being the now-famous band, ABBA (winners in 1974).

“It’s a European thing, and we love to compete with each other,” senior Sara Wohler from Wohlen, Switzerland, said. “Every country has to say which one is the best singer and then there is someone who wins the contest, and you can be really proud as a country when you win that.”

Despite the taboo surrounding a transsexual status Wurst, born as Thomas Neuwirth, won Eurovision in 2015 sporting a beard complete with a mustache, along with her feminine body.

“I think she [kept the beard] because she is also kind of representing transgenders/transsexuals and that she wanted to show the world that she can do that and I mean, she won the contest,” Wohler said. “That’s amazing, and she will be always in the minds of the people because it was so special to have not just a transgender, but also someone who you really can see has two genders.”

But the acceptance shown to Wurst isn’t necessarily the story for some countries across Europe, and even less so in parts of Asia and the Middle East. Twenty-three European countries have laws requiring transgender people to undergo sterilization before their gender identity is recognized, according to a map released just this year by Transgender Europe. Countries requiring sterilization include France, Italy, Russia, Norway, and Finland.

Meanwhile, in Korea, even the mention of the trans population is rare. A survey conducted in 2006 by Korea’s Democratic Labor Party and LGBT non-governmental organizations found that roughly 65.4 percent of the transgender people surveyed received insults, 44.9 percent experienced sexual harassment and 20.5 percent were victim to sexual assault. Furthermore, 37.7 percent and 36.4 percent said they endured or ignored such abuses, respectively, all to avoid an increase in discrimination or to prevent their gender identity from becoming public.

“At least in Korea, anybody who isn’t the regular heterosexual, cisgender person, is seen as either, A, they just don’t exist, or B, it’s completely looked down upon,” sophomore Kris Cho said. “In the community I see around myself in the United States, I can be a little bit more progressive, especially amongst the newer generation, but the thing is that it’s still super taboo in the community itself because there’s this idea that the Korean American just isn’t going to part of that community and that sort of representation just doesn’t exist.”

In order to change the legal sex on official documents in Korea, applicants need to meet nine criteria, including evidence of a diagnosis, participation in hormonal treatment and genital surgery, undergo sterilization, and have no child or spousal relationships. These 2006 guidelines released by the Korean Supreme Court champion some of the most restrictive rules for document changes. The requirements to receive sex reassignment surgery only include being at least 20 years of age and again, having no child or spousal relationships.

“It’s just something that we don’t talk about. Education is key, informing the public, informing the people, so that people start being interested in their own identities so that they can actually be true to themselves. But the thing is that Korea doesn’t facilitate that. Korea just doesn’t talk about it,” Cho said. “Where I am, at least in my community in Korea with my family, I’ve never heard of the concept of transgender in Korean. I had to look it up in English. I’ve never heard this issue spoken about in Korea, but I do know for sure that this is super taboo.”

Discussion on the transgender community in the Middle East is also one based on ridicule. Although scholars at the world’s oldest Islamic university, Al-Azhar [Cairo, Egypt], declared gender reassignment surgery as acceptable under Islamic law in 1988, the transgender population in the Middle East and other Islamic territories is still subject to ridicule and social discrimination from their family members and the community.

“In the case that there is someone who is … not cisgender, those people are almost automatically almost alienated [in Korea,]” Kho said.

“Really they just don’t believe that what they’re saying is true. They can’t comprehend that it’s an actual feeling,” junior Divya Divya said. “They also make fun of them, even openly, which is just horrible.”

Combating discrimination and mistreatment of the trans population slowly, the supreme court of India passed a legal breakthrough on April 14, 2014, granting transgender people, called “hijras” in India, the right to be recognized on official documents under a “third gender” category. Unfortunately like many other countries, these legal revisions still let social prejudice and discrimination run rampant.

“I would say that there’s not a lot of [transgender people]. There are a lot of strict family values in India, so you don’t see a lot of that,” junior Keerthi Prekumar said. “They’re talked about negatively, but also in a lot of TV shows. They make comedies of transgender people and things like that.”

Before the British colonial occupation of India, the population highly revered hijras and thought they brought luck. They even called on hijras to perform badhai, blessings at weddings and births. Once British powers took over in 1858, the prevailing negative western views on anything other than heterosexual or cisgender took over the legal and societal view on transgender people.

In 1860, the ruling powers passed section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, outlawing “Carnal intercourse against the order of nature.” This law was abolished in 2009, and five years later, the groundbreaking “third gender” category was included on legal documents.

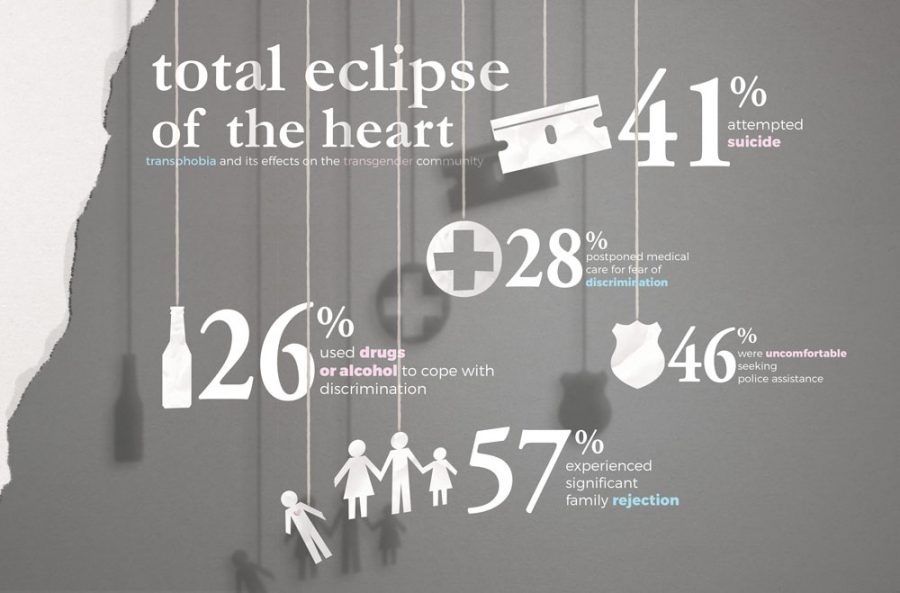

Unfortunately, doubters rival every step toward granting transgender individuals their due rights. From public ridicule in the media and on the streets to lessons instilled in children at a young age, the concept of transgender still holds a negative, shameful image in many parts of the world.

“It’s very frowned upon in the Islamic country, just because their rules are so strict and they just don’t think that a man should be a woman. When we were younger, we were kind of told, ‘Stay away from them,’ and they’re not ‘pure,’” Divya said. “Also, they kind of believe that this is all an attention pull; it’s not actually who they are. They are a man. It is very, ‘You shouldn’t do it. It’s bad. It’s against the religion.’”

In almost all cases, the status of transgender overshadows any other accomplishment or trait of an individual.

“It doesn’t matter from where you came or what color your skin is. It’s just a part of you,” outreach counselor Lesley Thalhuber said. “Just because someone is transgender, doesn’t mean they identify as lesbian, gay, or even bisexual.”

But in Korea, identifying as transgender sometimes serves as the worst failure. Based on what Cho has seen during her visits to Korea, even though there are laws that allow transgender people their due rights, societal views still contain disdain and disgust.

“In the case that there is someone who is, even just identifying as not straight, not cisgender, those people are almost automatically almost alienated,” Cho said. “It’s sort of like this, ‘My kid didn’t get into Harvard, but at least he’s not gay,’ or, ‘at least he’s not transgender.’ There’s definitely a strong set belief [that] you have to conform.”

The transgender community deserves to voice their stories and be freed from oppression, just as every individual deserves to retain rights to their own story, regardless of their culture, as emphasized by Thalhuber. Whether people view transgender positively or negatively the basic courtesy of respect should still exist.

“Just put your assumptions aside. You just have to be open and also not too intrusive. It’s not like if you know someone in the LGBT community, they just want to talk about that issue all the time,” Thalhuber said. “There’s more to someone who identifies as LGBT than their status of being an LGBT person in the community. I don’t want people to get stuck on that one thing about someone.”

By Alice Yu