On Sept. 25, 1980, China’s then-ruler, Deng Xiaoping, changed China’s history.

Xiaoping introduced China’s infamous “one-child policy” on that day in order to support the country’s economy while simultaneously balancing an exponentially increasing population. With a limit of one child per couple, the policy was an attempt to curb population growth within China.

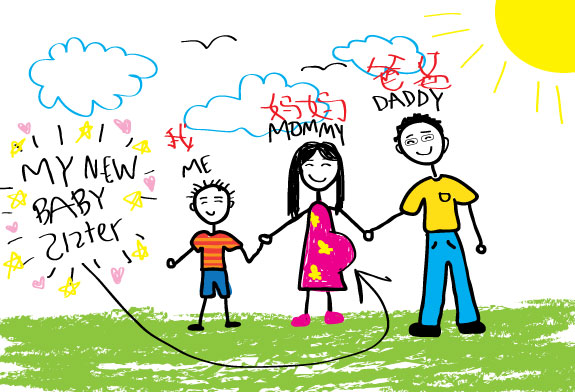

Nearly 35 years later, the Communist Party of China has reconsidered and announced the infamous policy would be formally changed to a two-child policy effective Oct. 29, 2015. The law’s recent revision will legally allow Chinese couples to have two children in their family instead of one.

Having lived in China previously for a period of time and experiencing the one-child policy’s effects, RBHS World Studies teacher Lee Franklin said that the policy is a game-changing event for China’s history.

“This is a very big deal,” Franklin said in an e-mail interview. “China caught a lot of flak from the international community in regards to its one-child policy. However, this is more of a big deal when it comes to the families of China and what the implementing if this policy represents for its citizens.”

RBHS students agree with Franklin in the sense that this policy change is rather significant. Sophomore Donia Shawn, while not having ties to China, is relieved that the policy has finally been modified.

“Personally, I’m actually really happy because it’s nice to see that they are able to have more children and aren’t limited to only one child,” Shawn said. “I feel like they chose to adapt to the new two-child policy because the citizens didn’t like the whole one-child policy. People are probably more content now.”

Along with Shawn, sophomore Laith Almashharawi is also pleased that Chinese families do not have to endure the possible life-changing terrors from the Chinese government concerning a second child any longer.

“On a first glance, it seems that the government did this to discourage the bad things that its citizens do because of the one-child law, such as female infanticide, unregistered second and third children in hiding and a female and male population imbalance, and still have some population control,” Almashharawi said. “I think in a rights perspective this is great, and it should always be kept as an example for acquiring more Chinese citizen freedom.”

The Chinese government’s decision to adjust the policy was based on an aging population that was not growing quickly enough. While the initial goal for the policy was to enhance China’s growth by reducing the country’s birth rate, the policy is arguably the main factor in China’s dangerously slow population growth.

In fact, according to the New York Times, China’s birth rate is down to an extremely low level, with every couple averaging just 0.7 children. Looking at this dangerous statistic, the Chinese government decided it was time to officially make the change.

“I think the Chinese government evaluated their situation and where they are at now and came to the conclusion that they are able to move past the one-child policy,” Franklin said. “However, I think they do not want to get to the point where their population booms out of control. So they decided to take a step towards opening up the family size, but still have some measures of population control.”

Franklin went on to thoroughly explain the policy’s lasting effects on citizens. During his residency in China, he had encountered many instances of the one-child policy’s consequences on households, including closer family relationships with extended relatives.

“Most families I encountered only had one child,” Franklin said. “This led to their extended families being very closely knit. Often, they would refer to their cousins as ‘my brother or my sister.’ This is because they spent time around each other as immediate families. Still, I know people who had/have a desire to have a sibling. You could have more than one child in China under the one child policy, you just had to pay a tax in order to have another child. This meant only the wealthier people had more than one child. The exception was twins. If you had twins, you could keep them. Some people were envious (in a good way) of those in China who had siblings. Now, more people will be able to experience having a sibling.”

While the one-child policy was an attempt to control China’s exponentially high population growth, it resulted in several disadvantages for the Chinese, including a significant imbalance between the genders. The New York Times stated that there were about 25 million more males of marriageable age than similarly-aged women. However, the population imbalance will likely subside with the two-child policy now in effect.

More importantly concerning the policy is that Chinese couples now have the long-due right to raise an extra child. While the policy still regulates the amount of children a couple can legally possess, it is certainly a step in the right direction and will hopefully lead to an even more lenient policy in the future.

“I am glad that China is at the point to where their families can now be extended if they so choose,” Franklin said. “While some in the past have condemned or looked down upon China for having the one-child policy, I was not one in that camp. I believe the policy was an unfortunate necessity for China. The idea of restricting family size seems bad to us, but no longer being able to sustain yourself is even worse. Still though, choice and freedom is better and I am glad that China is at the point to where they can give their citizens more choice.”

art by Ana Ramirez

What is your opinion on China’s one-child policy?