I am a feminist. Those who know me would likely say I wear the label proudly and loudly. I used to be of the mind set that those who eschewed the term were operating under misconceptions of what the feminist movement actually represents.

Now, I’m not so sure.

This summer I attended a camp titled Women’s Debate Institute, where feminist discussions seemed inevitable. On the second day, we engaged in a short activity where the floor represented a scale from agree to disagree and campers were to move to the side of the room that aligned with their views.

The first question was simple: Do you identify with feminism?

After a flurry of activity, everyone had landed in a distinct camp. The majority was firmly in the ‘agree’ faction, and I felt momentarily vindicated. But when I looked across the room, I saw a glaring, unmistakable distinction between the two groups; the majority of those who did not call themselves feminists were black.

Every individual forms her or his own feminism, but the feminism that seems to be gaining the most public support is the kind that belongs to people like Emma Watson and Taylor Swift: white and privileged.

This is not an all-whites-are-bad brigade. I, an Asian female, have most certainly been guilty of unintentionally overlooking narratives that differ from my own. I have spoken out about issues such as rape culture, soft sexism and the struggles of professional women in male-dominated careers, but have failed to talk about how these issues affect women of color, whose perspectives are seldom highlighted in feminist discussion.

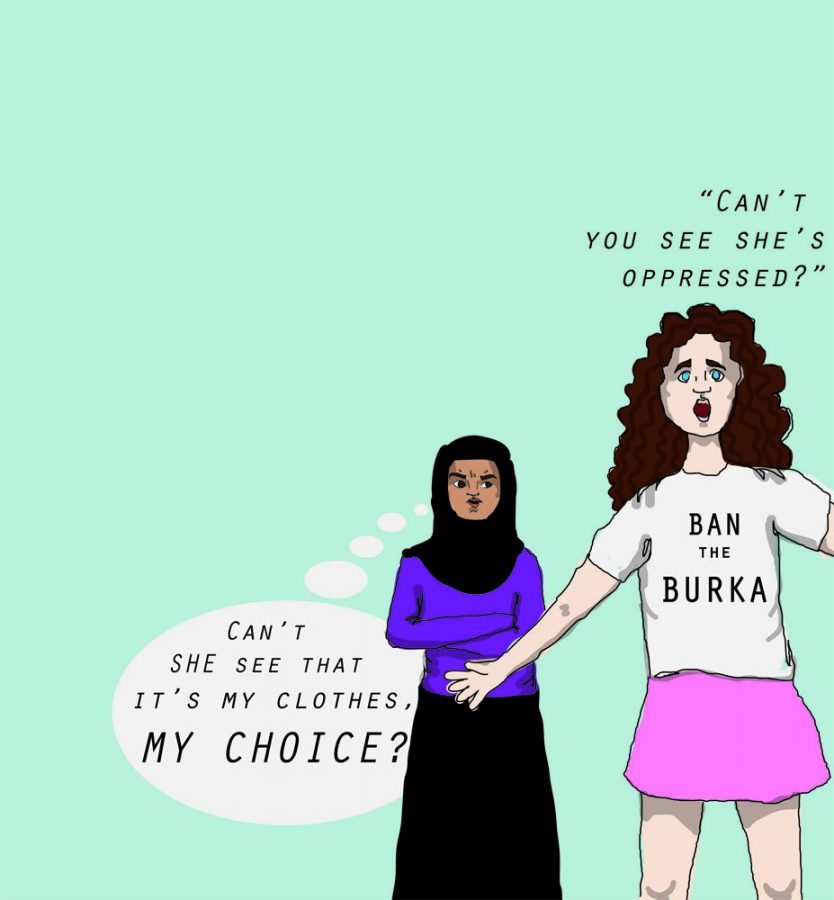

We cannot hold ‘Free the Nipple’ rallies while ignoring how transgender bodies are both sexualized and disparaged. We cannot castigate rape culture without acknowledging how racial minorities are disproportionately affected by sexual violence, according to Sexual Assault Response Services of Southern Maine. We cannot force women in certain cultures to conform to our own ideas of ‘female liberation.’

The belief that feminism needs to incorporate the voices of all racial and gender minorities is known as intersectionality theory, a term coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw. Intersectionality theory gained further prominence when sociologist Patricia Hill Collins spoke extensively on it in her works about black feminism, where she wrote that ‘rather than examining gender, race, class and nation as distinctive social hierarchies, intersectionality examines how they mutually construct one another.’

Well-intentioned, yet somewhat clueless mainstream feminists often drown out countless minority voices.

This was shown when Sheryl Sandberg, the CEO of Facebook, garnered criticism for her book “Lean In,” which many perceived as ignorant of race, class and sexual identity. Prominent feminist author Bell Hooks penned a piece that lambasted “Lean In” for its supposed ‘faux feminism.’

In the article, Hooks wrote that Sandberg’s book ignores the systematic obstacles that minority women face and, instead, instructs women how to succeed in a man’s world in a way that is only possible for white women of privilege to do.

It is easy to overlook underrepresented voices, but that disregard can no longer be allowed to happen. Whether or not you identify as a feminist, including different perspectives and encouraging diversity in social discourse is essential across the ideological spectrum. This is not the time to get sensitive about privilege. I know that when I saw such a clear racial divide at my summer program, I was tempted to defend both myself and the feminist movement; I wanted to jump in with arguments about how the purpose of feminism is to help all women.

After hearing the stories of some amazing black feminists, I was able to gain a deeper understanding of how unwelcome certain minorities feel in a campaign dominated by white women. They helped me realize the damage I was doing by not seeing the racism in feminism. Now, I can no longer discuss feminist issues without considering the perspectives of women of color.

Have I abandoned feminism? The answer to that is no. But I have certainly learned to recognize the deep flaws of a movement that has been an enormous part of my identity. After going through that painful realization, I can no longer advocate for feminist issues without considering their impacts on women of color.

It’s never easy to admit that your ideology is problematic, but it has to happen if we want to have an honest discussion about intersectionality in feminism.

Categories:

Lack of intersectionality damages the movement

October 5, 2015

0

More to Discover