[vc_custom_heading text=”The Night” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Roboto%3A100%2C100italic%2C300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C500%2C500italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C900%2C900italic|font_style:500%20bold%20italic%3A500%3Aitalic” css=”.vc_custom_1429302501777{padding-top: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;}”]Editors note: Story contains graphic language.

[dropcap style=”flat” size=”5″ class=”A”]T[/dropcap]eenagers like to push limits. They go out to see a movie without parent permission or secretly hang out with their boyfriend. They go skinny-dipping at midnight or swipe a pack of gum from the gas station. But how much trouble could they get into in one night?

No one expects their night’s actions to land them in prison. It would be completely unimaginable for one night, one moment, to send a future careening in a different direction: No college. No job. No freedom.

But on the night of April 7, 2012, Lamar Mayfield, then a 15-year-old student at Jefferson Junior High School, went with friends to a high school party, and his future flipped in an instant when he fired a gun and killed another boy, a 17-year-old, formerly enrolled at RBHS, who, Mayfield said, had been an enemy for a long time.

“Bryan [Rankin Jr.] reach for a gun, and I reach for my gun,” Mayfield said, “and I end up hitting him before he got me, and my cousin grabbed [me] and pushed me off. We take off running, and I throw the gun.”

On the streets, Mayfield said, getting in trouble with the law is not a big fear. Teenagers sell drugs, carry guns and get in fights, he said. Such a lifestyle is not a question of morality; it’s simply survival.

Mayfield grew up in this environment, but in many ways he was a normal kid, with lots of friends he would do anything for and a family he loved. But unlike many kids, Mayfield got in a lot of fights, real fights. Mayfield even had a gun.

“My family [started me on the streets] because usually you don’t just decide to jump in. You were kind of born in it. My family gang bang or if they didn’t gang bang, then it’s streets selling drugs, shooting people; you know what I’m saying?” Mayfield said. “Then people I was hanging with that were doing that, and I just ended up getting sucked up with the activities, doing what they was doing. And that was it. Getting a little bit of money off of selling drugs and carrying guns, everything. You get born in it. You don’t just decide to jump in cause if they do just decide to jump in they don’t last.”

So many pressures weighed on Mayfield. Everyone had a different expectation for him. While the streets were his life, he knew at times he was letting others’ decisions become his choices, even if that wasn’t necessarily what he wanted for himself.

“You got a lot of people doing different things out there. It’s a lot of distractions. [I’m] not [going to school] every day; sometimes I just wouldn’t feel like it, and I wouldn’t go,” Mayfield said. “I was just slacking, I think. But you also got a lot of people that you think you’re cool with try to take over your mind and get you to think something different and just being around certain people and these people got problems and then their problems become your problems. I mean, they just get deeper and deeper and then they end up coming to me and when they see each other, they see they going to push on you, or you’re going to push on them.”

So Mayfield learned to do a lot of the pushing. He learned to defend himself and be independent at a young age. And on this night he felt the familiar tug while he and friends were at a party.

“I got a gun with me because I know the college parties get wild, so just in case something happened I got this gun with me,” Mayfield said. “But I don’t tell nobody because a lot of people when they got weapons or whatever they a little bit harder, a little bit tougher and everything. So I just played it cool. I had a gun, but I ain’t telling nobody.”

When his friends decided to attend a party at a different apartment, everyone piled into five cars. Mayfield said he didn’t want to leave but also didn’t want to seem like he wasn’t “chill.”

When they got to the high school party, Mayfield encountered Bryan Rankin Jr.. Mayfield and Rankin Jr. had a history, Mayfield said, and not a good one. Mayfield said he didn’t want to start anything but the two argued until Rankin Jr. left. So he and his friends got in a car again, set to find Rankin Jr.

And they did. Rankin Jr. and his brother were in a parked car. One of Mayfield’s friends had intended to fight but was nervous, so Mayfield stepped in. He walked up to the car and immediately felt the tense energy hanging in the air. Screams and curse words tore at the night as everyone was momentarily filled by the fear and exhilaration of the potential fight that lingered in the thick air.

“So I go to his car. I’m talking to him I’m like, ‘Wassup bro? What are y’all doing?’ and they yelling and everything. He was all like ‘B—h ass dude…’, all this and that blowing on everybody, so that’s why I go up to the car and I’m like, ‘Wassup with you, man? What you want?’” Mayfield said. “‘I’m like, ‘Wassup? What y’all yelling for?’ So I grab a Grey Goose bottle, I smack the window with it —boom— and I smacked the window cause now they doing all this faking. I was just gonna call him out, and we was gonna fight, or we was just gonna jump him. Whatever.”

But they didn’t just fight. Instead Mayfield caught a glimpse of Rankin Jr.’s gun, and the next instant truly changed the lives of Mayfield, Rankin Jr., and their families forever.

After a long trial process, including “lawyering up” then dropping the private attorney in lieu of a public defender, challenging his initial sentences, Mayfield was certified as an adult, pleaded guilty to second degree murder and sentenced to 17 years, with his first chance at parole after 85 percent of his sentence has been served.

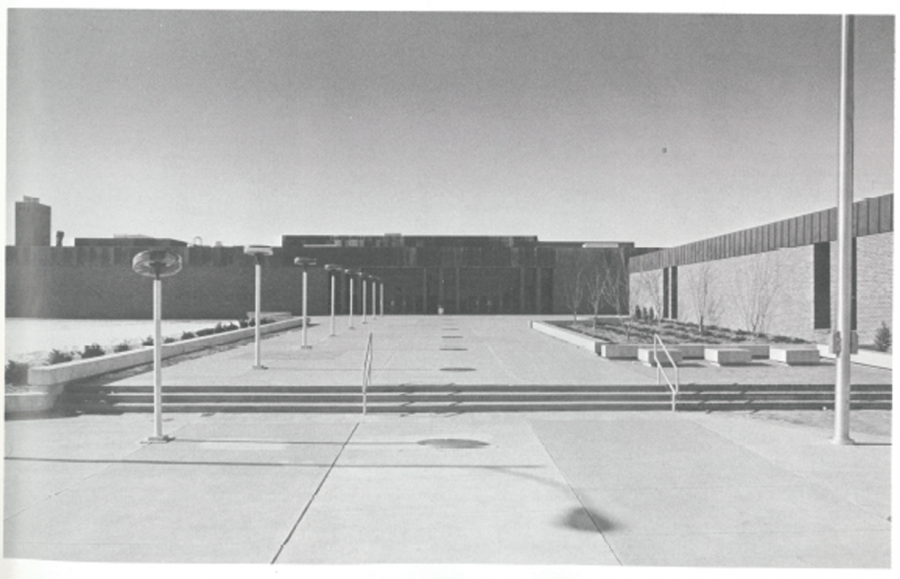

For the next 17 years, Mayfield’s life is on pause.[/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Life in Prison” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Roboto%3A100%2C100italic%2C300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C500%2C500italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C900%2C900italic|font_style:500%20bold%20italic%3A500%3Aitalic” css=”.vc_custom_1429302719355{padding-top: 20px !important;}”]The cream-color building is already ominous with a tall chain-link fence and sharp barbed wire poking out from the top. This fence cuts off the South Central Correctional Center from the surrounding rural, Missouri town, Licking. A smoke stack emits a fog that only adds to the dismal feeling the building emits. For more than 1,000 inmates, this is the only view they have seen in months, sometimes years, and in cases decades.

While the rest of the world keeps moving forward, the lives of all these inmates remain stagnant. Mayfield is 18 now, but besides aging, he doesn’t change much. He has been to three different facilities, arriving at South Central only in December. These moves are the biggest changes he has experienced in three years.

Each day of the week is laid out in the same structure. Mayfield falls into a routine. There is little room for individuality. Every gray jumpsuit is filled with an offender waiting for a chance to be a person again, to make their own decisions.[/vc_column_inner]“Mondays we come out in the evening. We got evening rec, so I chill, get on the phone. I’ll probably go outside. I don’t smoke, the majority of the people smoke, so I’d be working out,” Mayfield said. “Tuesdays we got morning rec, which is from 8-10:55. Evening rec is 1:20-4. Sometimes if it’s bad weather, they’ll lock the prison down, and we only get night shifts, so we come out for 30 minutes, even though we only done that a couple of times since I been here.”

Doing the same things every day can be disorienting and distancing. Many of the memories of his life before are cleared away by the mind-numbing routines of prison. Mayfield couldn’t even remember how long he has been at the South Center Correctional Center.

“We only done that a couple of times since I been here, I just got here uh… What’s the date today?” Mayfield said. “I got here on [Jan.] 18th, so I been here about almost two months. No, almost three months.”

Mayfield said prisoners don’t look at the time they have left as years, or weeks. Instead. each hour, each minute, each second passes slowly, painfully, consciously. Measurements of time fade as clocks lose their importance and all time morphs into one never-ending moment.

He must follow rigid protocol 24 hours of the day, like waking up at 6 a.m. for morning counts and for going to solitary confinement, known by inmates as the “hole,” if he gets into a fight or breaks a rule.

“[The hole is] if you act up. I mean with a fight sometimes a CO (correctional officer) will get on [you.] Stealing and all of that gets you in there. You’re locked down 24 hours a day, you and another person, unless you on suicide, or you in protective custody or something they’ll put you in the cell by yourself. And every other day beside Saturday, you got outside for the night, but if it feel good outside, they’ll chop your time in half. But if it’s bad outside, they’ll leave you out for the longer, so you don’t wanna come out no more. Every three days we [have the opportunity to] take a shower” when in the hole, Mayfield said. “I just did two months. You know, I was in there 30 days for the fights. And I got 30 [when I transferred]. Usually when you come from a lower level to a higher level you usually going to be there a little longer cause you had to do something bad enough for them to sit you in the hole and up your level cause they know they got somewhere that’s disattached from us.”

The “hole” gives time for clarity. Mayfield says while there he studies or reads, but it can also lead prisoners to a perplexed mental state. Inmates can be sent to the hole for a myriad of reasons, from taking an extra chicken patty —everyone’s favorite— during lunch or fighting another inmate who calls them a name, such as “hoe, b—h, and p—y.”

Mayfield calls these “fighting words.” No one wants to go to the hole, but no one is afraid to defend themselves to gain respect and hopefully instill fear in potential challengers. Most teens couldn’t imagine having to stand up to a murderer or rapist just to protect their chicken patty.

Mayfield also thinks about mortality more than most teens. He is adamant about not dying in jail. While he only has a little under 15 years left on his sentence, he knows bad health could mean he could waste his already shortened time when he does finally get out.

Many prisoners smoke every day to take off the edge that prison sharpens. He avoids smoking and inhaling second hand smoke. His cellmate, whom he refers to as his “cellie,” have worked out a system where his cellie smokes in front of a fan pointed out of the cell, so all the smoke leaves the room.

“I ain’t smoke when I was on the street. On the street a lot of people smoke weed to get you high, but I don’t do nothing to get you high,” Mayfield said. “A cigarette, that can get you cancer, an upgrade. So if I’m not smoking weed, I ain’t gonna smoke no cigarette and risk my life and get cancer when I get out or die in here. I just leave that alone.”

Working out has also been a pass-time Mayfield practices to maintain his health. When he is in the hole, he exercises as hard as he can, drenching himself in sweat, meaning he has to spend up to three days sitting, stinking, in his own room. Mayfield has taken up new hobbies, too, while in the hole, such as reading. He said he’s read part of the Maximum Ride series by James Patterson, an activity he would never have taken time for before prison.[/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Preparing to Leave” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Roboto%3A100%2C100italic%2C300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C500%2C500italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C900%2C900italic|font_style:500%20bold%20italic%3A500%3Aitalic” css=”.vc_custom_1429303669484{padding-top: 20px !important;}”]Learning to enjoy reading isn’t the only skill Mayfield is concerned about. During his time in prison he realizes he is falling behind in the ever-changing world of technology and increasingly becoming distant from societal norms and structures.

Since he was incarcerated, several new iPhones have come out, smart watches have taken off, Google Glasses have intrigued many, 3D printers have expanded their abilities, and drone technology has skyrocketed.

It is hard for Mayfield to imagine a world of technology, as he doesn’t even have access to the internet in prison. Mayfield also can’t imagine being immersed in a quick-paced, loud world again. Even sitting in the visiting room in the prison, every noise causes him to whip his head around to get a view. He is at all times hyper-aware of his surroundings. He admits he is verging on paranoia.

“The first month will be the hard part of getting back to the society. I gotta be used to the technology, used to the language, used to the movement and all the commotion and try to be grown, so I gotta get out there and do grown man stuff that’s legal because I’m not trying to come back here with no charge or come back here at all,” Mayfield said. “They gonna make me apply for a job right off the cuff, but if they don’t rock with me, they don’t rock with me. Because this stuff I got to do it for myself. I can’t just jump back in there like nothing happened. I got to get right with myself, then, after that, I still won’t apply for no job until I get my license because I ain’t finna rely on no one else because if they late to pick me up, then I’m late to work, and I got to take that up with my parole officer. I just got to get everything on track.”

In order to make up for lost time in high school, Mayfield has taken classes in prison in order to pass the GED test. Taking classes in prison can be harder because the environment is not as conducive to learning as a school is. Most inmates don’t value education, and therefore slack off in class: heckling teachers and talking over lessons.

Mayfield said if he knew he would end up in prison, he would have stayed in school. Here it is almost impossible for him to gain knowledge when being surrounded with such a violent and rude ambiance.

“It was hard as a motherf—-r. Because here you have to take pre-GED, and the GED. But the … test you got to have at least a nine and the lowest is L, and If you get in the L level you can’t read. When I passed everything, I was in the hole because, I mean, you got people in the class you can talk to. Even if you’re not talking, you still can’t focus just because you got people talking around you. I went to the hole. I got good. I got the reading. I got the studying because I was in the cell by myself so at the other prison, because there weren’t enough people in the hole, I got the cell by myself so when I was down there I had the teacher bring me some books, dictionary, stuff like that, so I can study,” Mayfield said. “Took the pre-GED. I passed it. I took the GED, and I failed social studies, and I got out the hole, and I got here, and they let me take social studies again, and I passed it just like a couple of weeks ago, so I just got my diploma or whatever for that.”

Receiving a GED is only a part of Mayfield’s preparation for his life after prison. But being only 16 when he was sentenced and getting 17 years, Mayfield was facing a life in jail longer than his life on the streets. He missed out on developing his morals, his personality, his people skills and many other lessons teenagers learn in their young, formative years.

Being so young and being stacked up against so many years is a challenge Mayfield sees in many of the inmates with larger sentences around him, a flaw in the whole design of the prison system he said. With no experience in the real world, these inmates become too calloused and inexperienced to cope with leading a normal life.

“My cousin got life at 17. That’s a long time. There is another dude who been locked up since he was 15, and he’s 40 now. I can understand with the crime they did. They might have did something gruesome. But after you lock a person up for that long don’t expect them to get out and be cool now because they don’t want to go back to prison. They done a lot of time, a lot of years. All they know is standing up for themselves and violence, so don’t send them back that’s all they know,” Mayfield said. “That dude who got locked up who’s 40 now, when he was 15, Xbox wasn’t out, and PlayStation wasn’t out, and so when I get back out, all this stuff gonna be here and people gonna be talking crazy and he’s been doing this for 30 some years. He ain’t finna feel comfortable changing back to all the stuff in society. He is gonna be like, ‘Man, send me back to prison. This is my home this is where I am from.’ There ain’t none of that trying to change. He’s been here for too long.”

Still, Mayfield said he is glad he got a longer sentence because it will encourage him to stay out of trouble when he is finally freed. He said his friends and other prisoners often get minor charges and are in and out of prison in a year or two. These people become repeat offenders because they were not changed by their consequences.

Mayfield has had lots of time to think, think about his family and the heartache his mom has gone through. He remembers his parents coming to see him after he was arrested, before the process of trialing began, to see their son before he was convicted and before he was whisked away to a penitentiary. They realized their time together was draining away, minute by minute, slipping by.

“My mom come in crying. Me and my dad talk. They come in. They like, ‘You got armed criminal action and second degree murder. You’re going to have a certification hearing if you wanna take it down to JJC,’ and I’m like all right. I’ll listen to that, and I’m cool,” Mayfield said. “I’m talking to my mom and dad over here crying, so now she crying all at me, so I get to crying.”

Mayfield knows the power of time. He sees how each day can destroy friendships as people forget him while his life is on hold. He has used his days to ponder what he will tell his little brother, who will be a teenager by the time he is released.

“Basically anybody that is rockin with me now, I am gonna rock with you when I get out, and that is just how it’s gonna be,” Mayfield said. “If you get into it with somebody, I am gonna get into it with somebody. Know what I am saying? It is just how I am, but at the same time I am also gonna try to keep my head clear from their nonsense cause when I get out, I got a little brother, so I am gonna have to be on him.”

Mayfield wants his brother to be aware of the downsides of being on the street. However, he knows that teenagers hate to be told what to do. He said he will show his brother the good sides, too, and hope his brother makes smart decisions.

He says the lifestyle isn’t always what it is painted to be. Skipping out on school also means skipping out on developing social skills and living out childhood with a carefree demeanour. Prison is the last place he wants any of his family to land, but already some of his cousins and other extended family members are.

“I was 15 doing grown man stuff while all the 15-year-olds were doing their 15-year-old things,” Mayfield said. “Whatever you wanna know, I am pretty sure I know about it, so I am not gonna chose your life for you, but whatever you do I’m gonna tell you what is good about it and what is bad about it. A lot of guys in here tell a lot of stories when you get locked up, a lot of guys will be like “I was selling this on the street, this and that.’ They gonna brag about it, like ‘I had this rollie. I had cars. I had women, all this and that,’ but they ain’t got no money now, and then sometimes, half the times, they are still be going to school. There are guys 40 still in school, ain’t even got their GED, so it is just crazy, they won’t tell you about when they robbed, they ain’t gonna tell you about how many times they been arrested and how much time they was facing, and they was crying. I am gonna tell you both sides and let you decide on your own.”

Ultimately, his time to think has lead him to see what he wants for his life. While he will always hold true to his friends and family, he also holds true to what he knows is right for him individually, even if others disagree.

“If I could start over again, I would have done everything the same. I just wouldn’t have walked up to the car because that’s really what set everything off. I wouldn’t have walked up to the car, left it alone,” Mayfield said. “If I could give myself advice, I would say, ‘Don’t try to be grown at a young age. Live your young age. When you got to get grown, be grown. Do what’s right because what you do affects everybody.’”

By Abby Kempf[TS_VCSC_Icon_Flat_Button button_style=”ts-color-button-emerald-flat” button_align=”center” button_width=”100″ button_height=”50″ button_text=”Previous” button_change=”true” button_color=”#ffffff” font_size=”18″ icon=”ts-awesome-chevron-left” icon_change=”true” icon_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_html=”false” tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-top” tooltipster_offsetx=”0″ tooltipster_offsety=”0″ margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″ link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bearingnews.org%2F2015%2F04%2Funder-pressure%2F|title:Under%20Pressure|”]This article is the fourth in a series. Select “Next” to view the next article in the series, or “Previous” to view the preceding article. Return to Quick Navigation.

[dropcap style=”flat” size=”5″ class=”A”]T[/dropcap]eenagers like to push limits. They go out to see a movie without parent permission or secretly hang out with their boyfriend. They go skinny-dipping at midnight or swipe a pack of gum from the gas station. But how much trouble could they get into in one night?

No one expects their night’s actions to land them in prison. It would be completely unimaginable for one night, one moment, to send a future careening in a different direction: No college. No job. No freedom.

But on the night of April 7, 2012, Lamar Mayfield, then a 15-year-old student at Jefferson Junior High School, went with friends to a high school party, and his future flipped in an instant when he fired a gun and killed another boy, a 17-year-old, formerly enrolled at RBHS, who, Mayfield said, had been an enemy for a long time.

“Bryan [Rankin Jr.] reach for a gun, and I reach for my gun,” Mayfield said, “and I end up hitting him before he got me, and my cousin grabbed [me] and pushed me off. We take off running, and I throw the gun.”

On the streets, Mayfield said, getting in trouble with the law is not a big fear. Teenagers sell drugs, carry guns and get in fights, he said. Such a lifestyle is not a question of morality; it’s simply survival.

Mayfield grew up in this environment, but in many ways he was a normal kid, with lots of friends he would do anything for and a family he loved. But unlike many kids, Mayfield got in a lot of fights, real fights. Mayfield even had a gun.

“My family [started me on the streets] because usually you don’t just decide to jump in. You were kind of born in it. My family gang bang or if they didn’t gang bang, then it’s streets selling drugs, shooting people; you know what I’m saying?” Mayfield said. “Then people I was hanging with that were doing that, and I just ended up getting sucked up with the activities, doing what they was doing. And that was it. Getting a little bit of money off of selling drugs and carrying guns, everything. You get born in it. You don’t just decide to jump in cause if they do just decide to jump in they don’t last.”

So many pressures weighed on Mayfield. Everyone had a different expectation for him. While the streets were his life, he knew at times he was letting others’ decisions become his choices, even if that wasn’t necessarily what he wanted for himself.

“You got a lot of people doing different things out there. It’s a lot of distractions. [I’m] not [going to school] every day; sometimes I just wouldn’t feel like it, and I wouldn’t go,” Mayfield said. “I was just slacking, I think. But you also got a lot of people that you think you’re cool with try to take over your mind and get you to think something different and just being around certain people and these people got problems and then their problems become your problems. I mean, they just get deeper and deeper and then they end up coming to me and when they see each other, they see they going to push on you, or you’re going to push on them.”

So Mayfield learned to do a lot of the pushing. He learned to defend himself and be independent at a young age. And on this night he felt the familiar tug while he and friends were at a party.

“I got a gun with me because I know the college parties get wild, so just in case something happened I got this gun with me,” Mayfield said. “But I don’t tell nobody because a lot of people when they got weapons or whatever they a little bit harder, a little bit tougher and everything. So I just played it cool. I had a gun, but I ain’t telling nobody.”

When his friends decided to attend a party at a different apartment, everyone piled into five cars. Mayfield said he didn’t want to leave but also didn’t want to seem like he wasn’t “chill.”

When they got to the high school party, Mayfield encountered Bryan Rankin Jr.. Mayfield and Rankin Jr. had a history, Mayfield said, and not a good one. Mayfield said he didn’t want to start anything but the two argued until Rankin Jr. left. So he and his friends got in a car again, set to find Rankin Jr.

And they did. Rankin Jr. and his brother were in a parked car. One of Mayfield’s friends had intended to fight but was nervous, so Mayfield stepped in. He walked up to the car and immediately felt the tense energy hanging in the air. Screams and curse words tore at the night as everyone was momentarily filled by the fear and exhilaration of the potential fight that lingered in the thick air.

“So I go to his car. I’m talking to him I’m like, ‘Wassup bro? What are y’all doing?’ and they yelling and everything. He was all like ‘B—h ass dude…’, all this and that blowing on everybody, so that’s why I go up to the car and I’m like, ‘Wassup with you, man? What you want?’” Mayfield said. “‘I’m like, ‘Wassup? What y’all yelling for?’ So I grab a Grey Goose bottle, I smack the window with it —boom— and I smacked the window cause now they doing all this faking. I was just gonna call him out, and we was gonna fight, or we was just gonna jump him. Whatever.”

But they didn’t just fight. Instead Mayfield caught a glimpse of Rankin Jr.’s gun, and the next instant truly changed the lives of Mayfield, Rankin Jr., and their families forever.

After a long trial process, including “lawyering up” then dropping the private attorney in lieu of a public defender, challenging his initial sentences, Mayfield was certified as an adult, pleaded guilty to second degree murder and sentenced to 17 years, with his first chance at parole after 85 percent of his sentence has been served.

For the next 17 years, Mayfield’s life is on pause.[/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Life in Prison” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Roboto%3A100%2C100italic%2C300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C500%2C500italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C900%2C900italic|font_style:500%20bold%20italic%3A500%3Aitalic” css=”.vc_custom_1429302719355{padding-top: 20px !important;}”]The cream-color building is already ominous with a tall chain-link fence and sharp barbed wire poking out from the top. This fence cuts off the South Central Correctional Center from the surrounding rural, Missouri town, Licking. A smoke stack emits a fog that only adds to the dismal feeling the building emits. For more than 1,000 inmates, this is the only view they have seen in months, sometimes years, and in cases decades.

While the rest of the world keeps moving forward, the lives of all these inmates remain stagnant. Mayfield is 18 now, but besides aging, he doesn’t change much. He has been to three different facilities, arriving at South Central only in December. These moves are the biggest changes he has experienced in three years.

Each day of the week is laid out in the same structure. Mayfield falls into a routine. There is little room for individuality. Every gray jumpsuit is filled with an offender waiting for a chance to be a person again, to make their own decisions.[/vc_column_inner]“Mondays we come out in the evening. We got evening rec, so I chill, get on the phone. I’ll probably go outside. I don’t smoke, the majority of the people smoke, so I’d be working out,” Mayfield said. “Tuesdays we got morning rec, which is from 8-10:55. Evening rec is 1:20-4. Sometimes if it’s bad weather, they’ll lock the prison down, and we only get night shifts, so we come out for 30 minutes, even though we only done that a couple of times since I been here.”

Doing the same things every day can be disorienting and distancing. Many of the memories of his life before are cleared away by the mind-numbing routines of prison. Mayfield couldn’t even remember how long he has been at the South Center Correctional Center.

“We only done that a couple of times since I been here, I just got here uh… What’s the date today?” Mayfield said. “I got here on [Jan.] 18th, so I been here about almost two months. No, almost three months.”

Mayfield said prisoners don’t look at the time they have left as years, or weeks. Instead. each hour, each minute, each second passes slowly, painfully, consciously. Measurements of time fade as clocks lose their importance and all time morphs into one never-ending moment.

He must follow rigid protocol 24 hours of the day, like waking up at 6 a.m. for morning counts and for going to solitary confinement, known by inmates as the “hole,” if he gets into a fight or breaks a rule.

“[The hole is] if you act up. I mean with a fight sometimes a CO (correctional officer) will get on [you.] Stealing and all of that gets you in there. You’re locked down 24 hours a day, you and another person, unless you on suicide, or you in protective custody or something they’ll put you in the cell by yourself. And every other day beside Saturday, you got outside for the night, but if it feel good outside, they’ll chop your time in half. But if it’s bad outside, they’ll leave you out for the longer, so you don’t wanna come out no more. Every three days we [have the opportunity to] take a shower” when in the hole, Mayfield said. “I just did two months. You know, I was in there 30 days for the fights. And I got 30 [when I transferred]. Usually when you come from a lower level to a higher level you usually going to be there a little longer cause you had to do something bad enough for them to sit you in the hole and up your level cause they know they got somewhere that’s disattached from us.”

The “hole” gives time for clarity. Mayfield says while there he studies or reads, but it can also lead prisoners to a perplexed mental state. Inmates can be sent to the hole for a myriad of reasons, from taking an extra chicken patty —everyone’s favorite— during lunch or fighting another inmate who calls them a name, such as “hoe, b—h, and p—y.”

Mayfield calls these “fighting words.” No one wants to go to the hole, but no one is afraid to defend themselves to gain respect and hopefully instill fear in potential challengers. Most teens couldn’t imagine having to stand up to a murderer or rapist just to protect their chicken patty.

Mayfield also thinks about mortality more than most teens. He is adamant about not dying in jail. While he only has a little under 15 years left on his sentence, he knows bad health could mean he could waste his already shortened time when he does finally get out.

Many prisoners smoke every day to take off the edge that prison sharpens. He avoids smoking and inhaling second hand smoke. His cellmate, whom he refers to as his “cellie,” have worked out a system where his cellie smokes in front of a fan pointed out of the cell, so all the smoke leaves the room.

“I ain’t smoke when I was on the street. On the street a lot of people smoke weed to get you high, but I don’t do nothing to get you high,” Mayfield said. “A cigarette, that can get you cancer, an upgrade. So if I’m not smoking weed, I ain’t gonna smoke no cigarette and risk my life and get cancer when I get out or die in here. I just leave that alone.”

Working out has also been a pass-time Mayfield practices to maintain his health. When he is in the hole, he exercises as hard as he can, drenching himself in sweat, meaning he has to spend up to three days sitting, stinking, in his own room. Mayfield has taken up new hobbies, too, while in the hole, such as reading. He said he’s read part of the Maximum Ride series by James Patterson, an activity he would never have taken time for before prison.[/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Preparing to Leave” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Roboto%3A100%2C100italic%2C300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C500%2C500italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C900%2C900italic|font_style:500%20bold%20italic%3A500%3Aitalic” css=”.vc_custom_1429303669484{padding-top: 20px !important;}”]Learning to enjoy reading isn’t the only skill Mayfield is concerned about. During his time in prison he realizes he is falling behind in the ever-changing world of technology and increasingly becoming distant from societal norms and structures.

Since he was incarcerated, several new iPhones have come out, smart watches have taken off, Google Glasses have intrigued many, 3D printers have expanded their abilities, and drone technology has skyrocketed.

It is hard for Mayfield to imagine a world of technology, as he doesn’t even have access to the internet in prison. Mayfield also can’t imagine being immersed in a quick-paced, loud world again. Even sitting in the visiting room in the prison, every noise causes him to whip his head around to get a view. He is at all times hyper-aware of his surroundings. He admits he is verging on paranoia.

“The first month will be the hard part of getting back to the society. I gotta be used to the technology, used to the language, used to the movement and all the commotion and try to be grown, so I gotta get out there and do grown man stuff that’s legal because I’m not trying to come back here with no charge or come back here at all,” Mayfield said. “They gonna make me apply for a job right off the cuff, but if they don’t rock with me, they don’t rock with me. Because this stuff I got to do it for myself. I can’t just jump back in there like nothing happened. I got to get right with myself, then, after that, I still won’t apply for no job until I get my license because I ain’t finna rely on no one else because if they late to pick me up, then I’m late to work, and I got to take that up with my parole officer. I just got to get everything on track.”

In order to make up for lost time in high school, Mayfield has taken classes in prison in order to pass the GED test. Taking classes in prison can be harder because the environment is not as conducive to learning as a school is. Most inmates don’t value education, and therefore slack off in class: heckling teachers and talking over lessons.

Mayfield said if he knew he would end up in prison, he would have stayed in school. Here it is almost impossible for him to gain knowledge when being surrounded with such a violent and rude ambiance.

“It was hard as a motherf—-r. Because here you have to take pre-GED, and the GED. But the … test you got to have at least a nine and the lowest is L, and If you get in the L level you can’t read. When I passed everything, I was in the hole because, I mean, you got people in the class you can talk to. Even if you’re not talking, you still can’t focus just because you got people talking around you. I went to the hole. I got good. I got the reading. I got the studying because I was in the cell by myself so at the other prison, because there weren’t enough people in the hole, I got the cell by myself so when I was down there I had the teacher bring me some books, dictionary, stuff like that, so I can study,” Mayfield said. “Took the pre-GED. I passed it. I took the GED, and I failed social studies, and I got out the hole, and I got here, and they let me take social studies again, and I passed it just like a couple of weeks ago, so I just got my diploma or whatever for that.”

Receiving a GED is only a part of Mayfield’s preparation for his life after prison. But being only 16 when he was sentenced and getting 17 years, Mayfield was facing a life in jail longer than his life on the streets. He missed out on developing his morals, his personality, his people skills and many other lessons teenagers learn in their young, formative years.

Being so young and being stacked up against so many years is a challenge Mayfield sees in many of the inmates with larger sentences around him, a flaw in the whole design of the prison system he said. With no experience in the real world, these inmates become too calloused and inexperienced to cope with leading a normal life.

“My cousin got life at 17. That’s a long time. There is another dude who been locked up since he was 15, and he’s 40 now. I can understand with the crime they did. They might have did something gruesome. But after you lock a person up for that long don’t expect them to get out and be cool now because they don’t want to go back to prison. They done a lot of time, a lot of years. All they know is standing up for themselves and violence, so don’t send them back that’s all they know,” Mayfield said. “That dude who got locked up who’s 40 now, when he was 15, Xbox wasn’t out, and PlayStation wasn’t out, and so when I get back out, all this stuff gonna be here and people gonna be talking crazy and he’s been doing this for 30 some years. He ain’t finna feel comfortable changing back to all the stuff in society. He is gonna be like, ‘Man, send me back to prison. This is my home this is where I am from.’ There ain’t none of that trying to change. He’s been here for too long.”

Still, Mayfield said he is glad he got a longer sentence because it will encourage him to stay out of trouble when he is finally freed. He said his friends and other prisoners often get minor charges and are in and out of prison in a year or two. These people become repeat offenders because they were not changed by their consequences.

Mayfield has had lots of time to think, think about his family and the heartache his mom has gone through. He remembers his parents coming to see him after he was arrested, before the process of trialing began, to see their son before he was convicted and before he was whisked away to a penitentiary. They realized their time together was draining away, minute by minute, slipping by.

“My mom come in crying. Me and my dad talk. They come in. They like, ‘You got armed criminal action and second degree murder. You’re going to have a certification hearing if you wanna take it down to JJC,’ and I’m like all right. I’ll listen to that, and I’m cool,” Mayfield said. “I’m talking to my mom and dad over here crying, so now she crying all at me, so I get to crying.”

Mayfield knows the power of time. He sees how each day can destroy friendships as people forget him while his life is on hold. He has used his days to ponder what he will tell his little brother, who will be a teenager by the time he is released.

“Basically anybody that is rockin with me now, I am gonna rock with you when I get out, and that is just how it’s gonna be,” Mayfield said. “If you get into it with somebody, I am gonna get into it with somebody. Know what I am saying? It is just how I am, but at the same time I am also gonna try to keep my head clear from their nonsense cause when I get out, I got a little brother, so I am gonna have to be on him.”

Mayfield wants his brother to be aware of the downsides of being on the street. However, he knows that teenagers hate to be told what to do. He said he will show his brother the good sides, too, and hope his brother makes smart decisions.

He says the lifestyle isn’t always what it is painted to be. Skipping out on school also means skipping out on developing social skills and living out childhood with a carefree demeanour. Prison is the last place he wants any of his family to land, but already some of his cousins and other extended family members are.

“I was 15 doing grown man stuff while all the 15-year-olds were doing their 15-year-old things,” Mayfield said. “Whatever you wanna know, I am pretty sure I know about it, so I am not gonna chose your life for you, but whatever you do I’m gonna tell you what is good about it and what is bad about it. A lot of guys in here tell a lot of stories when you get locked up, a lot of guys will be like “I was selling this on the street, this and that.’ They gonna brag about it, like ‘I had this rollie. I had cars. I had women, all this and that,’ but they ain’t got no money now, and then sometimes, half the times, they are still be going to school. There are guys 40 still in school, ain’t even got their GED, so it is just crazy, they won’t tell you about when they robbed, they ain’t gonna tell you about how many times they been arrested and how much time they was facing, and they was crying. I am gonna tell you both sides and let you decide on your own.”

Ultimately, his time to think has lead him to see what he wants for his life. While he will always hold true to his friends and family, he also holds true to what he knows is right for him individually, even if others disagree.

“If I could start over again, I would have done everything the same. I just wouldn’t have walked up to the car because that’s really what set everything off. I wouldn’t have walked up to the car, left it alone,” Mayfield said. “If I could give myself advice, I would say, ‘Don’t try to be grown at a young age. Live your young age. When you got to get grown, be grown. Do what’s right because what you do affects everybody.’”

By Abby Kempf[TS_VCSC_Icon_Flat_Button button_style=”ts-color-button-emerald-flat” button_align=”center” button_width=”100″ button_height=”50″ button_text=”Previous” button_change=”true” button_color=”#ffffff” font_size=”18″ icon=”ts-awesome-chevron-left” icon_change=”true” icon_color=”#ffffff” tooltip_html=”false” tooltip_position=”ts-simptip-position-top” tooltipster_offsetx=”0″ tooltipster_offsety=”0″ margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″ link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bearingnews.org%2F2015%2F04%2Funder-pressure%2F|title:Under%20Pressure|”]This article is the fourth in a series. Select “Next” to view the next article in the series, or “Previous” to view the preceding article. Return to Quick Navigation.

Skyler Froese • Apr 19, 2015 at 4:50 pm

What gets me in this story is that we were at the same school at the same time. I didn’t know him or even know of him. I can’t remember anyone even giving whispers about in the hallway, I can’t even remember the crime. It feels so strange to have been so indifferent to something so close.