[heading size=”16″ margin=”10″]Teachers debate whether universal standard benefits students[/heading] The public school system in the United States already faces scrutiny for placing high importance on standardized test scores. Missouri House Bill 365, recently introduced by Missouri Rep. Bryan Spencer (R-Wentzville), aims to become another notch in the number of hurdles high school students currently face.

The bill proposes that every student, starting in the 2018-19 school year, must score proficient or above on one of several approved tests in order to graduate with a Missouri high school diploma. The tests mentioned in the bill are the ACT, the ASVAB, the GED, the COMPASS, or four end-of-course exams in each of the four core subjects of mathematics, communication arts, social sciences and science.

Students such as junior Karson Ringdahl fear that, if passed, this bill could potentially alienate students who suffer from test anxiety or excel in nontraditional subjects. Students who scored below the proficient benchmark could have their education invalidated.

“I feel like there are a lot of smart people who struggle with tests, and hard work would be looked over,” Ringdahl said. “Plus, it would be very expensive to have multiple standardized tests implemented into our school system.”

Although the bill may seem threatening to the students who would be affected — students who don’t even attend RBHS yet — guidance counselor and head of testing Betsy Jones reassures that the overwhelming majority of RBHS students would not have to worry about the seemingly vague “proficient” threshold.

“By the time they are seniors they will be proficient in subjects they perhaps weren’t earlier,” Jones said. “It might hurt other schools though, but we have much stronger academics.”

Additionally, some tests provide safeguards between each other. The COMPASS test, given at RBHS, provides a completed test for algebra if a student didn’t meet the required score on the algebra end-of-course exam.

“I am giving the COMPASS tomorrow to students who were not proficient in Algebra 1,” Jones said. “But you can show that proficiency on the COMPASS or the ACT if you didn’t on the end-of-course. So rather than re-give the EOC, I’m giving these students the COMPASS.”

There are more concerns educators have about the bill, such as its vague structure and lack of specificity concerning English Language Learners students and students with individualized education programs.

“I think it’s problematic,” special education teacher John Cooley said. “A one-size-fits-all kind of test is going to do a disservice to a lot of students, because everyone has their own personal strengths and weaknesses that could be put to good use in the post-secondary world that’s not covered in the range of the test.”

Spencer, however, believes the exceptions and modifications offered to students in special education programs will not alienate them or impede their graduations further.

“They can have the modification as indicated by their Individualized Education Program and restricted by the [Missouri] Department of Elementary and Secondary Education,” Spencer said. “As long as the testing agency’s test validity is not compromised.”

Nevertheless, Cooley worries not all students can proficiently test, even if their program lowers the standard of proficiency. Another qualm he has with the bill is that some students he teaches may excel in technology or art or any kind of field not included in college preparatory and standardized tests, devaluing their level of education and potential contributions to the workforce.

“Students that I work with that have Individualized Education Programs will not excel in those four core areas, but they’re very intelligent and they excel at technical skills that lead to positions like electricians who are highly skilled,” Cooley said. “But those tests aren’t going to test their skills. What message does that send to kids who aren’t going to college, but are going to technical schools; that you are a lesser member of society because you are not college-bound?”

By Luke Chvalphoto by Caylea Erickson

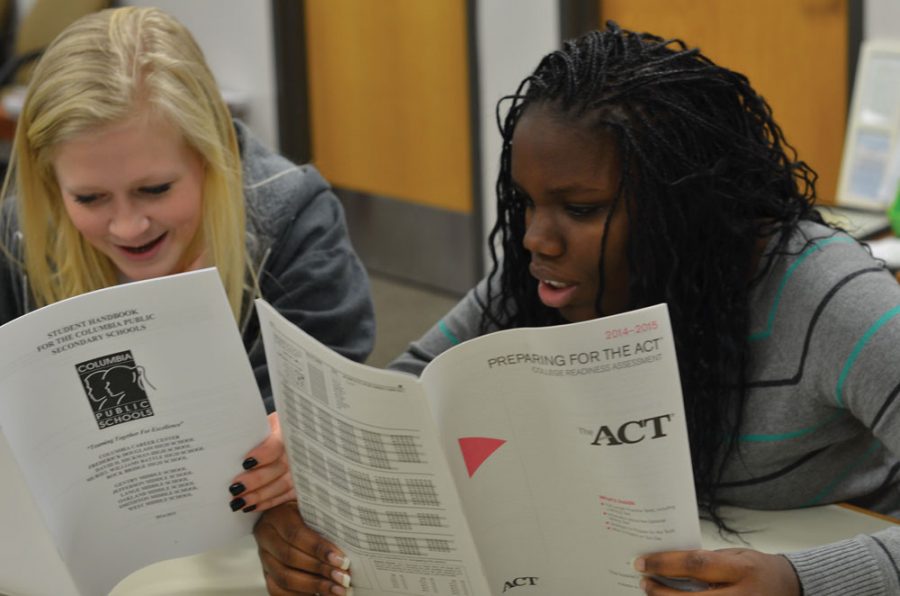

Studying for the test: Sophomores Mackenzie Marison and Janylah Thomas look through informative materials about standardized tests and course work. Missouri H.B. 365 would make standardized tests necessary to graduate high school.

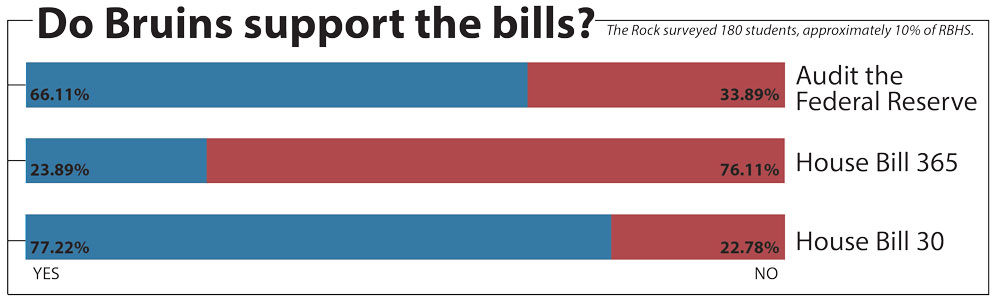

infographic by Emily Franke

poll by Devesh Kumar