Veto of pipeline bill puts it to rest — for now

Imagine if green energy was the sole type of energy running the world, with houses powered by the Sun and cars powered by electricity gathered from the wind. Imagine if oil was a thing of the past and if the world used the free energy given from the environment.

Now imagine a world where all the energy used is from oil and then, suddenly, this non-renewable resource ran out. Panic would cross the globe and the world would go dark.

That day will eventually happen. Somewhere down the road, oil will run out. Until then, the world will continue to search for oil beneath the surface and discover cheaper ways to get energy.

And right now, corporations have turned to tar sand oil. Canada has millions of barrels of tar sand oil under its surface, and TransCanada, an oil company, is attempting to extract it and profit from it just like any other business would.

TransCanada had a dream to build a pipeline from southern Canada all the way to Texas. So far, that dream has been a success, with three out of the four stages of construction complete.

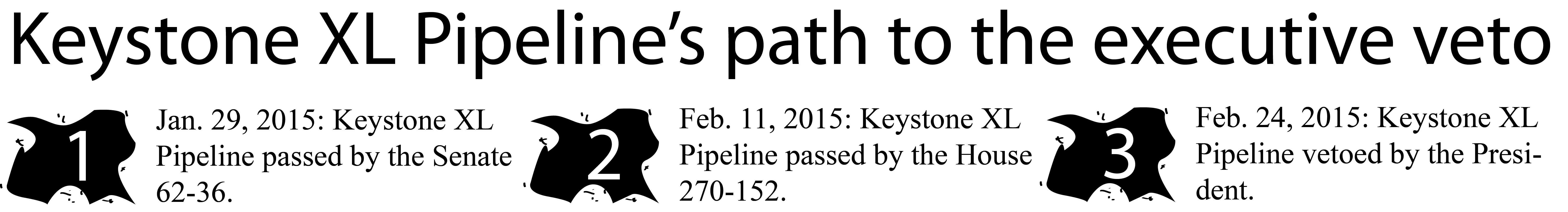

Within the past month, Congress has sent a bill to the President approving the final stage of the pipeline. On Feb. 24, President Obama, with the swipe of his executive pen, vetoed the bill Congress sent him.

infographic by Abdul-Rahman Abdul-Kafi

While this may seem like the end of the Keystone XL Pipeline, it is merely the end of one attempt. Greg Irwin, AP World History teacher, said the Pipeline will be built somewhere down the road.

“It is a classic debate. I mean the whole debate is the classic ‘what is economically helpful versus [what is] environmentally harmful,’” Irwin said. “At the end of the day, [Keystone XL Pipeline] is gonna [be built].”

However, with Obama keeping his promise of the veto, it will take at least two more years — when the next president takes office — until there is another chance to make it happen. In the meantime, supporters of the President are relieved he kept his promise.

“I think he realizes the consequences it could have on the environment,” junior Ana Ramirez said. “He wouldn’t approve of something that is so risky and bad for the Earth when he stands with environmental groups, and he is a Democrat, so he wants what is best for the environment.”

In the November 2014 midterm election, one of the key debates from both sides of the political spectrum was over the Keystone XL Pipeline.

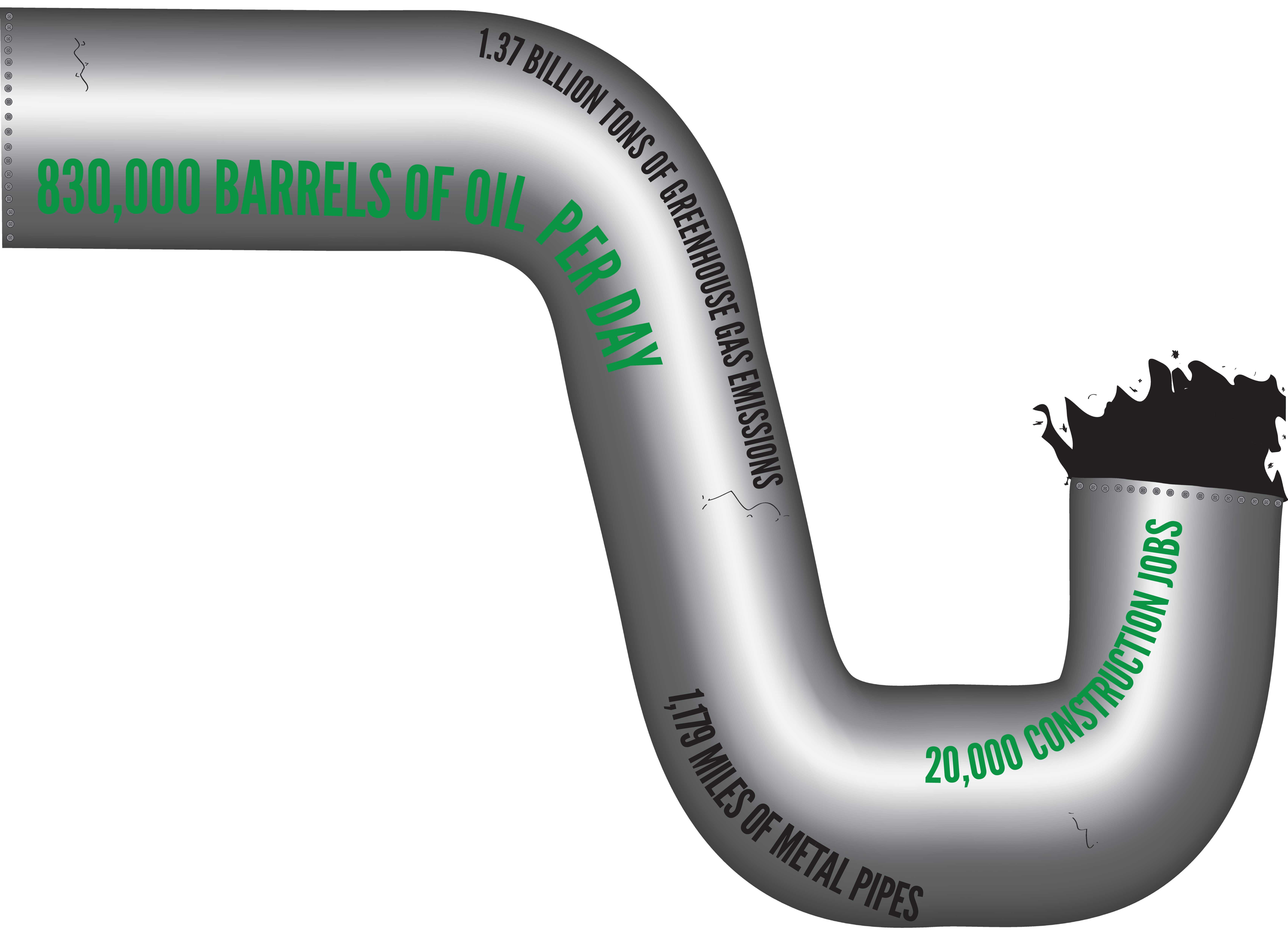

The current pipeline, stages one to three, travels east along the Canada-US border on the Canadian side a few hundred miles until it almost hits the Minnesota-Canada border, where it starts heading south to Port Arthur, Texas, near the Gulf.

The XL phase, or the currently vetoed fourth phase, would introduce a shortcut for the pipeline to travel, rather than the hundreds of miles above the Canadian border, in a diagonal from the start in Canada to Steele City, Nebraska.

The Keystone XL Pipeline would pump 830,000 barrels of crude oil per day, or 41.5 million barrels over its expected 50-year lifespan.

According to TransCanada, which is the corporation that would set out to hire workers to build the pipeline, this major construction venture would generate 20,000 construction jobs in the United States and would indirectly create 100,000 other jobs.

“I feel like usually industry overshoots [the number of jobs they will create],” Irwin said. “When IBM said they were going to bring Columbia over a thousand jobs, they brought 300. Knowing the way these business things work, it [will] probably be less than that.”

Those 100,000 other jobs that TransCanada says will be created would come from the hospitals, schools, housing and other necessities that the construction crew would need when they relocate to the site of the pipeline construction.

“Because these 20,000 people are going to be relocated, they need schools, they need hospitals, they need roads,” Irwin said. “Tax money [will go] to those states. All these sorts of things [are] profound arguments.”

The arguments Irwin brought up are in favor of the economic benefits that the XL Pipeline would bring to the states it would exist in. However, on the other side of the aisle, people argue that these jobs would just be temporary, and that when the pipeline is complete, the jobs would become obsolete.

“It may be a small, short-term benefit, and if you look at what the long-term cost is, it is just not worth it,” chemistry teacher Gregory Kirchhofer said. “If you dump money into economics to build a pipeline, you have a little bump and people move to this place, they move to Montana. This is what happens with the natural gas fracking in Montana, where it is a big boom. Everything goes up for a while and then you have a drop in prices and now you have thousands of unemployed people because it is not profitable anymore. It is not about getting energy, it is just about making money.”

Emissions from extraction, transport, refining and use of the oil brought from the Keystone Pipeline would add an estimated 1.3 to 27.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year into the atmosphere, according to a report by the Environmental Protection Agency, or the EPA.

“XL is tar sand oil, which is equivalent to what we used to do to strip mine for coal,” Kirchhofer said. “We are dragging all the surface off of the ground and heating it and adding chemicals to it and extracting the oil and then allegedly returning it to the ground. But you can’t just dig up thousands of acres of land and put it all back and expect it to be OK. It is just not the same.”

art infographic by Abdul-Rahman Abdul-Kafi

Kirchhofer said the use of energy resources today is only about the short term consequences and not about the long term, very similar to how the jobs created to construct the pipeline will only be short-term.

“When we tear up the land and we put chemicals in the ground, they end up in the streams, they end up in the ocean, they end up in the rivers. You cannot dump stuff and not have it go everywhere,” Kirchhofer said. “I think the idea of the Keystone Pipeline is more about making money for the companies who are extracting the fuel and a little bit of economic boost in temporary job creation, but the long-term damage is much more.”

Millions of people share Kirchhofer’s concern and just as many agree with Irwin’s arguments. When it gets down to it, the argument is whether or not the economic benefits that the pipeline would bring to the US and Canada outweigh the environmental concerns. To Ramirez, they do not.

“I really don’t think there are that many benefits compared to the consistency of the environment because really the environment is all we have and [the Pipeline] is not going to give us that many benefits,” Ramirez said. “I think that the Keystone [Pipeline] is a very bad idea and that it is very bad for the environment … because it is coming from crude oil, which is very thick and hard to transport. Also, extracting it would predictably take out 1.37 billion tons of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, which is absolutely terrible because we are trying to stop that by using clean energy and [the pipeline] is very dirty energy.”

Irwin believes while the environmental concerns are great and evident, for the time being, the economic benefits that the pipeline would bring to the US outweigh the environmental concerns.

“I think it is economic weight versus the environmental footprint,” Irwin said. “Typically, economic weight wins. When you attach a dollar sign to something and say the state universities in Wyoming or Nebraska could have this X extra money, people are like, ‘OK, yeah I will take that.’ So my prediction is [the pipeline] will happen, it is just a matter of time because it is a resource we desperately need. Until we end our dependence on gasoline and petroleum, we are going to keep looking to build and tap all the reserves of oil we can.”

Irwin believes in the free market. He trusts that eventually it will be more economically beneficial to use green energy rather than rely on fossil fuel. However, he realizes it will not be just by the flip of a switch.

“You have to make individual choices as a consumer and [you have to] pay some more upfront costs, but then there is a significant move for those alternative energies,” Irwin said. “I don’t think [the pipeline] will destroy the alternative energy movement or something like that. I think there are a lot of commentators that say there is not going to be a silver bullet for our independence on oil. Fracking is environmentally not great, but is it going to throw us into uncontrollable climate change all by itself? No, that’s not happening.”

Irwin recalled a documentary he showed to his world studies students a few years back.

“It said if we don’t control [carbon] emissions and all this stuff by this year, like by 2009, then by 2015 there will be uncontrollable climate change,” he said. “Miami and New York will be underwater. Shanghai will be underwater, and none of that has happened.”

While Irwin sees the climate change as being more far out into the future, Kirchhofer is not as optimistic.

“We ignore the cost of dumping tons and tons, millions of tons, I should say, of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere,” Kirchhofer said. “The other piece of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere that we tend to ignore is the effect on the oceans.”

Kirchhofer said if there is more carbon dioxide in the air, it will eventually mix with the water of the ocean, which would chemically produce an acidic substance.

“We are increasing the acidity of the oceans measurably and the majority of the things in the ocean that are the base of the food chain are small shelled animals,” said Kirchhofer, who believes building the rest of the Keystone pipeline will increasingly damage the environment. “Increased levels of acid dissolves calcium carbonate, which is what the shells are made from. We are losing animals and coral and micro-animals because the slight increase in acidity makes the carbonate unavailable to build shells with, so as we take away the base of the food pyramid there, everything else is collapsing with it.”

Irwin fears climate change will eventually cause disastrous change to the world. However, he does not think climate change will dissuade the politicians from approving the final stage of the pipeline.

infographic by Abdul-Rahman Abdul-Kafi

“Winters are getting colder; summers are getting hotter, but in general, global temperatures are increasing across the board, especially in the global south,” Irwin said. “Part of it is until it hits people in the pocketbook, until some of those significant things start happening, I just don’t see change where you get urbanized societies to buy into, to invest in those sorts of things. If energy becomes so expensive that solar panels are way, way, way worth it, like is sort of happening right now, especially in big cities, people are going to move to it. I don’t think the free market is perfect, but I believe enough in it that this sort of thing will happen. It sort of already is, but to expect everyone to buy into that overnight, I think is kind of, at least not realistic.”

By Abdul-Rahman Abdul-Kafi