Growing up in St. Louis, senior Michelle Yang had always held the dubious honor of being one of the only girls in her math classes. The self-described “Hermione Granger, but 10 times worse” had always been surrounded by strong, intelligent females, and nobody had ever told her that she could not do something because of her gender.

This changed in her fifth grade pre-algebra class when a male classmate leaned over and informed her that Yang could not be as good as math as him because she was a girl.

“That stuck out and I was sad about that, but then I got better grades than him,” Yang said. “I was mainly angry when he said that.”

This incident only strengthened Yang’s goal of going into a science field, which she has prepared for by taking AP Chemistry, AP biology and computer science classes. Throughout her scholastic career, Yang has consistently been one of few females in her science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) classes, particularly in her computer science course that she took in St. Louis.

“My classmates were really surprised I was there, and at the time I was playing tennis and had really preppy friends and they couldn’t reconcile that,” Yang said. “They could accept a girl, but she had to be nerdy and quiet, and I was not. I was loud and distinctly feminine.”

Today, women make up 12 percent of computer science graduates, a decrease from a high of 37 percent in 1984, according to a 2010-2011 Computing Research Association survey.

At the Columbia Area Career Center, girls make up around 10 percent of the computer science classes, teacher Nathaniel Graham said. Graham works in the computer science department at the CACC, and said this dearth stems from gender-specific cultural influences.

“Women are conditioned out of science fields by the way we just treat young boys and young girls as children,” Graham said. “Let’s say a family has multiple children, male and female, often the computer will end up in a spot that is favorable for the adult male or the male child.”

The under-representation of women is also prevalent in many other STEM fields such as engineering, but curiously fails to exist in career areas such as the life sciences, where the majority are women.

RBHS honors biology teacher Kaitlin Rulon said this shift is a result of a conglomeration of things, one being the general tendency of women to gravitate towards fields that involve caring for others.

“In general, women kind of have more of a disposition towards caring and things like that,” Rulon said. “So with the life sciences women seem to fit more because there’s more of a personal connection involved.”

However, Rulon said the greater numbers of women involved in the biological fields, where more than 60 percent of undergraduate majors are female according to a study published in the scientific journal Cell Biology Education, may also be a result of increased efforts on the parts of life sciences educators to expose young women to these subject areas.

“I think there’s been a better push from elementary and secondary education to encourage women to go into science related fields, where before I don’t think that was true,” Rulon said. “So I think there are just more women who have realized their passion or their interests in science from an earlier age.”

Here in Columbia, efforts to increase the exposure of engineering and programming at a young age already exist.

Graham said Russell Elementary has implemented a program that introduces girls and boys to such principles at the elementary level, where the gender divide in general science classes is a fairly even 50/50 split.

“There are classes that have recreated Columbia during different historical periods using Minecraft,” Graham said. “Right there we’re introducing everyone into architecture and building, and later on you can create logic blocks out of the blocks that Minecraft’s all about, which introduces programming concepts.”

Graham said efforts like this to provide increased opportunities to young women are important to combat the problems that persist in the field itself.

“Engineering has a problem where it’s a bunch of people like me, [a] generic white guy, and we have, generally speaking, the same cultural backgrounds and perspectives,” Graham said. “We view the world the same, we view problems the same, and that’s a huge issue when your job is to solve problems.”

However, junior Sydney Tyler say that while attempts to increase female representation are important, sometimes they can go too far.

“I do believe that if women are given awards, or positions or tenure on the basis of their gender it takes away from their accomplishments,” Tyler said.

Tyler has seen firsthand the realities of women in science, as her mother is the associate dean of graduate studies at the University of Missouri veterinary school, while she herself plans to go into the medical field as a physician. She said that if endeavors undertaken to increase representation of women in STEM fields, they should not be policy-oriented, but rather organic in nature.

“I don’t think that policy is an appropriate response, but an effort must be made,” Tyler said. “It needs to be a collective movement to encourage women to take part in STEM. I think growing up being told I was smart and that I could be whatever I want has freed me to make those decisions for myself.”

Junior Michael Pennella, a computer programming student at the CACC, concurred. He said that while female representation is important, policies such as quotas are misguided and ineffective.

“I think it’s a fine line between trying to increase representation and trying to force it,” Pennella said. “I think it’s great to increase the amount of opportunities marginalized groups can have, but I don’t believe that things like quotas accomplish that.”

Nevertheless, Pennella said that equal representation in STEM fields is still an essential goal that would be accomplished better through grass-roots movements.

“I think it’s one of the core principles of education to provide representation for all members of society, for all sexes, in these fields,” Pennella said. “I think that any change regarding this has to come from the ground up.”

Graham has already made efforts to do this through methods such as recruiting young girls into joining the computer science program at educational fairs, but said his endeavors alone will not do much to change the problem, which has its roots in decades of social conditioning.

“It’s a much larger issue than what one classroom can do,” Graham said. “It’s a cultural thing. Until we view Lego as a kid’s toy rather than a boy’s toy, until we say that everyone should learn to cook and sew, instead of regulating it to one half of the sexes, the issue can’t be resolved.”

By Jenna Liu

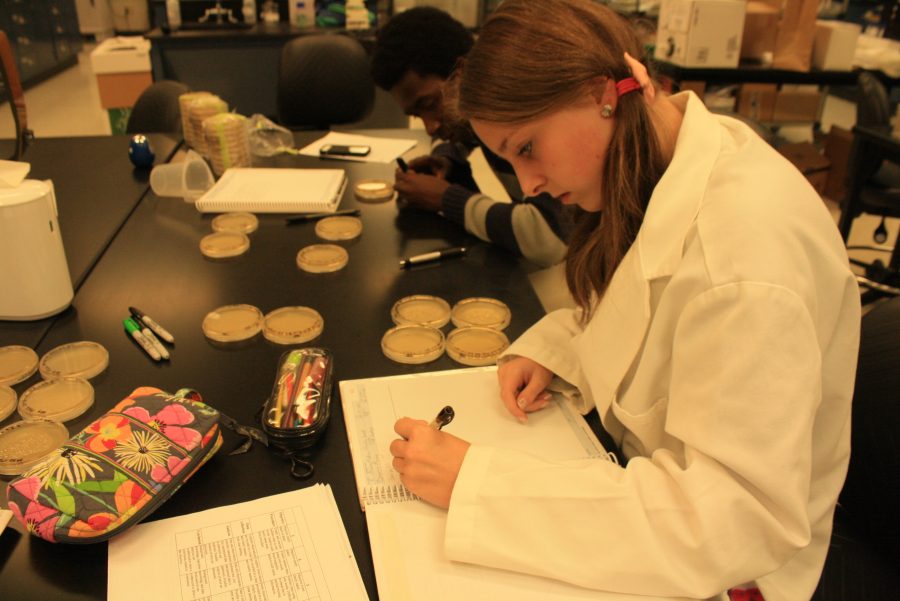

Junior Catherine Maring writes in her notebook for her 21st Century Life Sciences class.

Categories:

STEM fields see little growth in female representation

November 5, 2014

0

Tags:

More to Discover