After a health scare in senior Sarah Freyermuth’s family slightly altered her thinking, her whole life soon turned upside down as she developed anorexia nervosa. Freyermuth tried to suppress her mental illness and keep her battle hidden from her peers. Her journey was neither short nor painless, but in the end Freyermuth said she sees the good that can come from her run in with anorexia.

Facing the Problem

Everyone has a passion, and senior Sarah Freyermuth’s passion is for people. As an extrovert, she gets her energy from being around others; she loves listening to their stories, hearing their problems and being emotionally and physically available to her friends at all times.

“My way of living had become more than a habit, [it was] an obsession and a disorder.” Freyermuth said.

“I want to spend my life working with people and being with people and studying people,” Freyermuth said. “I’ve always been passionate about spending time with people, listening to their problems and just trying to be very present in all of my friends’ lives. Their friendships are all extremely important to me and people in general are extremely important to me.”

However, as she entered her junior year of high school, Freyermuth grew away from the people she so loved being with. A health scare sent her father to the hospital with high blood pressure. Following his hospitalization, Freyermuth’s family shifted to a healthier diet to help control his blood pressure.

Combined with the building stress of her junior year, what started out as a healthier diet became something much more serious. By October, Freyermuth had developed the early stages of anorexia nervosa.

“I think I just felt like a lot of things were out of control in my life. There was a lot of things that my dad wasn’t in control of with his health, and his doctor helped him to control it through diet,” Freyermuth said. “I think subconsciously I kind of latched on to that. It started out as simple little things; I started exercising a lot more and eating slightly less. It was not a big deal at all at the beginning, but then it started escalating from there. Soon it became a coping mechanism and then an obsession. It quickly stopped being about the weight and became just about the control that I felt like it gave me over my life.”

Anorexia nervosa, defined by Dr. Aneesh Tosh, University of Missouri Pediatric Specialty Clinic, is characterized by significant weight loss, obsessive fear of weight gain, abnormal body image and the restriction of food often in the context of overexercise. Dr. Tosh, who has 10 years of experience working with patients with eating disorders at the University, said most of his patients are adolescents who may not realize they have a problem and often rationalize their behavior as just being healthy.

Someone with anorexia could be diagnosed with normal anorexia or anorexia purging type, Mind Body Connections therapist Beth Parker said. In both cases, Parker said there may be symptoms besides weight loss, such as depression and anxiety. According to Parker, there is almost always a foundation of low self esteem, lack of confidence or feeling out of control.

After losing 10 pounds, then 20 within a few months, Freyermuth’s doctor remained unconcerned. This only propelled Freyermuth to eat even less and over-exercise, leading to a total loss of 30 pounds by January, the final 10 of which were lost in less than a month. The effects of her new regimen pulled her even more from the people she cared about.

“I kind of ceased to exist except for doing my school work. I tried to be there for my friends, but the thing was I spent almost all of my time exercising, measuring out my food, or sleeping,” Freyermuth said. “I kind of felt like I was going brain dead. It would get to the point where I really wanted to spend time with my friends but I just didn’t even have the energy to get out of bed. The other thing too is that you’re kind of ashamed of what you’re going through because of the stigma surrounding eating disorders. Because of that I grew apart from those that I used to spend all my time with because I was suddenly scared of what they would think if they knew.”

Often, individuals who struggle with eating disorders experience anosognosia, or an inability to see that they have a problem, according to feast-ed.org. This was not the case for Freyermuth. She knew she was struggling with anorexia; however, she felt separate from the disease.

“I knew there was something wrong, which is a little different,” Freyermuth said. “It wasn’t sinking in whatsoever. I knew in my head, ‘Yes, I have anorexia.’ I knew that I was starving myself; I knew that I was exercising way more than was healthy, but I guess I didn’t connect my tiredness and exhaustion to the reality which is heart failure and death.”

Without food, Freyermuth lacked not only physical energy but mental strength as well. On top of sleeping roughly three hours a night, feeling cold all the time and becoming paler than normal, Freyermuth found she began to spend more and more time alone. The more time she spent alone, the less time she spent with her friends, leading to a deterioration of the relationships she valued so much. When she saw her friendships suffering, she didn’t initially see her eating behaviors as the problem.

“I’ve always been a really determined, stubborn person so when I started growing apart from friends because of my nonexistent energy I was like ‘Oh I just have to work harder,’” Freyermuth said. “I guess … I knew what was going on, but I was kind of in denial about what it was doing to me. If I had seen a friend having this problem, I would be horrified, and I would want them to get help. But because it was happening to me, it was harder to admit to others what was going on in order to get the help I needed.”

A turning point for Freyermuth was when a friend, who is normally reserved and cautious when offering advice, said, ‘No, this is a problem.’ At this point, she realized her disorder affected more than just herself.

“It kind of hits you. When [that friend] said, ‘You’re not the same person at all anymore; you’re a completely different Sarah,’ that really, really hit me,” Freyermuth said. “That made me realize I couldn’t keep living like this. However, when I tried to make changes, I realized it wasn’t that easy; my way of living had become more than a habit, [it was] an obsession and a disorder. I think that’s kind of when I also realized that I couldn’t fix my anorexia by myself and so I needed to get help.”

By Emily Franke

Road to Recovery

As Freyermuth struggled with disordered eating, she kept it to herself, hiding what was happening so her family and friends couldn’t see. Although she suppressed her internal turmoil, those around her could easily see the effect anorexia had on Freyermuth’s body. Freyermuth said her friends and family were not surprised when she admitted her problem.

“With me and my mom, it hadn’t ever been a conversation of ‘What’s going on?’ It was more a conversation of me trying to convince her my anorexia wasn’t a problem. Fortunately, in this case I’m so, so bad at lying to my mom. She would know if I wasn’t eating or something like that,” Freyermuth said. “After I realized what was going on was actually a problem and I had my moment of clarity I went up and told her, ‘You need to get me help … if you ask me in five minutes, I’m going to say I don’t need help, so you need to go right now.’”

Getting help, it turned out, took several doctors and a long process of restoring health to her body and mind. The first doctor she went to remained unworried when her weight loss increased from 10 to 20 pounds. Her second doctor, who did seem concerned, was not well equipped to work with a patient dealing with an eating disorder, Freyermuth said. Finally, Freyermuth and her mom found a doctor they believe to be competent, Dr. Tosh, and Freyermuth started a program to gain back weight, which consisted of eating as much as three times the amount of food a normal person must eat to gain weight.

“My focus is the medical well-being of my patients,” Tosh said. “We do a medical history, physical examination and recommend appropriate testing, medications and referrals to a dietician and therapist. The first appointment is a long one, typically 60 minutes, as we like to talk with our patients alone and sometimes need to talk to the parents alone. We do a detailed medical history and physical examination. The patient will also meet with our dietician and typically will need blood drawn to look for medical problems.”

Following the first appointment, Tosh said, there are three important aspects to a patient’s recovery: medical, nutritional and behavioral. Therefore, patients need to see a physician, a dietician, and a therapist.

“I use the analogy of a car running out of gas. It can appear to everyone else that they are performing at a high level until the fuel runs out, then the body shuts down very quickly. The heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature all slow down — these are signs of starvation as the body is essentially trying to hibernate to save energy,” Tosh said. “Most of the time, patients appear in a fog or a haze, as the brain is struggling to survive with limited energy. Many parents tell me that their child’s personality and sense of humor disappear. For women who have stopped having periods, they have a significant risk of bone loss — osteopenia or osteoporosis — as well.”

However, these devastating effects of starvation can be reversed with proper medical treatment, Tosh said. Many times, he said, the medical and nutritional aspects are overcome sooner than the behavioral component, and it is important for patients to continue to work with their team until their care providers feel that they are in recovery, which can take several years with the possibility of a relapse, especially in the first two years of treatment.

“The effects are reversed with appropriate, medically monitored nutrition with the goal of restoring patients to a healthy body weight in addition to therapy to treat the underlying behavioral causes that led to the eating disorder,” Tosh said. “The earlier the patient is diagnosed and receives treatment, the better the prognosis. If [someone has] a friend whom they are concerned may have an eating disorder, they should mention their concerns to their friend that they should seek help. Many times, patients are much more responsive to a peer’s concern than from an adult. Appropriate adults to contact would be the friend’s parents, teachers or the school guidance counselor, nurse, coach or principal who can then assist with getting them to appropriate care.”

Visiting her doctor once every couple of days and her counselor once a week, she missed almost the entire month of February her junior year.

“The only thing that really kept me going through those days … was knowing I had to get better for my family and my friends —specifically for my mom because I knew how much I was upsetting her,” Freyermuth said. “Most people think ‘I need to eat to keep myself healthy for me.’ I didn’t start thinking like that until two months or three months down the road after [getting healthy]. The thing is with anorexia … is that your brain is starved … A lot of people think that if an anorexic person realizes the severity of their situation you can change their thought process and get them to eat. At least for me, my brain wasn’t functioning enough to realize how severe the situation was. I had to start eating before my thought process could really change.”

Initially, Freyermuth’s recovery relied on external change rather than internal change. She said a lot of people think change has to be internal; a person must know what they want to change and have the willpower to change it. Parker said she believes the eating disorder does not go away, but rather “you have to go away from it.”

She said she tells people that they have to learn to manage eating-disordered thoughts along with the anxiety, and they have to have the presence of mind to make good choices. Over time, she said, the thoughts will dissipate, but they may never go away.

When Freyermuth saw her behavior was upsetting her family and destroying her friendships, she persevered through the first stages of recovery just for them. It wasn’t until about a month after she had returned to a normal weight that she started realizing that she deserved to eat food and be healthy for herself, not just for other people.

“I kind of liken [eating disorders] to a virus … it can go into remission, like if you have a cold sore virus. You get stressed out and you have an outbreak and then it goes away for months, years, whatever,” Parker said. “It is said … that an average recovery time can be five to eight years and I think with some people it could be better in the beginning stages; it could be one year and some people have it the rest of their life … At various times in one’s life it can reemerge, but I don’t think it’s ever cured, per se.”

Stability, Parker said, is the return of a patient to a normal, healthy weight and the absence of restriction, along with the return of a female’s period. Also, she said, stability can be measured by the ability to relate to others and a return from isolation. For Freyermuth, recovering included reconnecting with her friends who she had grown away from.

“Often what you see is someone who previously was outgoing and very sociable and had bunches of friends will start spending more time alone … so isolation, along with other things, could be definitely a factor,” Parker said. “With anorexia you often see more rigidity, more anxiety [and] sometimes more obsessive compulsiveness. Getting back in your life is really important so that you can get that support.”

A lot of people will ask what they should say to their friends and family after treatment, Parker said, and she tells them to tell people they trust about their disorder. She often sees hesitancy among high school students to return to school immediately.

Although she said it is important for kids to get back into their settings, she also feels that returning to an environment where people don’t generally know about eating disorders can be more difficult than returning to a school that is more well-informed.

Because anorexia is such a visible disease, Freyermuth said, her friends had somewhat known what was happening the entire time, but she found acceptance and understanding when she told them what had happened. She said they seemed happy that she was willing to admit what was going on and they were supportive of her recovery.

“When I started getting better, all I wanted to do was spend time with people because I had missed out on so much of that,” Freyermuth said. “I remember one week I ended up hanging out with a different friend every single night, and I was so overwhelmed and exhausted by the end of the week because I realized I didn’t have the energy to do that anymore. Anorexia can take months or even years to recover fully from … I had to work my way back up to that.”

In retrospect, Freyermuth said society’s stigma on eating disorders slowed down her recovery and increased her sense of isolation. As a lifetime perfectionist, she said she was afraid to admit that something was wrong. While she initially found it easy to talk about her eating disorder, she said she also felt separate from that part of her life, so admitting it was like admitting someone else had a problem. Even with such support from her friends, it became harder to tell people what she had been through as she started connecting herself to her eating disorder.

No matter what career Freyermuth chooses, she said she wants to use her skills to work with mental health advocacy.

“I’m sure I had people that judged me, and I’m sure that people reading this article are going to judge me, too, because so many view anorexia as an ‘attention-getting disease.’ That is not what it is at all. Some people may think, ‘Oh, that’s not a real thing. She’s just making crap up,’ and the thing is that I’m OK with having people say that about me if I know that me doing this is going to help at least one other person who’s going through an eating disorder feel comfortable admitting it,” Freyermuth said. “If you hide your whole life from something that happened to you because one or two people don’t respect it then you can’t help the other people that are going through it.”

By Emily Franke

Spreading Awareness

During the spring of her junior year, Freyermuth discovered the ANNpower Vital Voices initiative, a program committed to empowering young women with leadership skills to allow them to positively influence in their communities. Applicants to the program outlined an idea that would effect positive change in their communities, according to annpower.vitalvoices.org. Chosen applicants are able to apply for grants to put their proposals into action.

Freyermuth said she felt blessed and lucky because of the ample support from friends, family and her medical team as she recovered from Anorexia. She had seen many friends without as much help in their recovery – in some cases she’d even seen loved ones egging a person on toward eating disordered behavior. Seeing her peers experience such isolation, Freyermuth contrived an idea to create a forum for people struggling with eating disorders to share their stories, read others stories and find information to help them fight this disorder that seemed to be otherwise unavailable.

“Sarah came to me like lots of students do with a big idea to enter a contest, except her idea was really unique … She wanted people to have a safe space to share their stories and then she wasn’t sure what format to use and so we talked about [PostSecret], but we wanted it to be longer than a postcard and it was really important to Sarah that people also have the chance to connect sort of more in real life like their not just putting it in a glass bottle and throwing it in the ocean,” EEE teacher Kathryn Fishman-Weaver said. “Then we talked technology, like could we have a blog? Could we have a website? What are some different ways we could use 21st century tools of communication? So I guess that’s sort of where it was born.”

With these values in mind, Weaver and Freyermuth considered a blog-style forum when they were inspired by Humans of New York, a blog that chronicles stories of average New York denizens.

“I really want to make a website where people can share their stories and comment on others” Freyermuth said. “That way there’s an online community where people can, either anonymously or not, feel like their story is being told in a community where no one will judge. This way, even if no one in their own geographic location understands what they’re going through, they know that there are people out there that understand them, [who] are fighting against the same thing and that aren’t stigmatizing them.”

Freyermuth entered the contest with an idea that she was passionate about, and she believed would positively influence her community as well as others. Her idea was not chosen; however, she still wanted to follow through with her website, whether or not she received support from ANNpower’s grants, fellowships or leadership seminars.

To create her website, Freyermuth contacted others she knew who had previously, or currently were, struggling with an eating disorder. She asked them if they would be willing to write their story, no matter how close or far, negatively or positively they were recovering. She received quick responses with their support. Weeks after, though, she said she had only gotten a couple stories.

“I’ve figured out very fast that most of them were either unwilling to write stories or when they did write stories found it very painful to write. A lot of the time by the time that someone’s willing to write their story it’s been misconstrued by time and rosy retrospective,” Freyermuth said. “People always put their experience in this really positive light when in actuality, an eating disorder is anything but a positive experience. I really wanted to have honest stories where people feel like, ‘Oh, I can really relate to this.’ I know for me when I was going through anorexia, I would look at stories of recovered anorexics who would say ‘oh I just woke up one day and the sun was shining and I got better’. It hurt me to read stuff like that because I was like, “OK, well, what’s wrong with me, I can’t connect with any of that.”

Freyermuth said a few people were willing to write down their stories, even if they were too scared to share them with her for the website. After finishing their stories, they contacted her with overwhelmingly positive feedback, saying that although the story had been incredibly hard to write, they felt so much more free once they had written it. That was the point of wanting to do this, she said, and sometimes just writing down an experience on paper, whether others read it or not, is a huge step toward admitting what you’re going through and recovery.

Other forms of online media devoted to eating disorders can be more sinister. Commonly referenced as “Pro-Ana (pro anorexia),” and “Pro-Mia (pro bulimia),” certain individuals in the online community encourage self-starvation, binging/purging, among countless other forms of self harm related to eating disorders. Freyermuth said these sites positively reinforce unhealthy behaviors in those who come across them.

“I see girls and boys that are like, ‘Yeah, starve yourselves. This is what you should be doing.’ It makes me sick,” Freyermuth said. “It sensationalizes something that’s absolutely terrible and I think that the media does a really good job of glamorizing a body-type that isn’t healthfully realistic for most and glamorizing a lifestyle that is healthy for none.”

On these sites, individuals “cheer each other on,” Freyermuth said, encouraging others to continue to starving themselves among other disordered eating behaviors. Not only does Freyermuth see this as wrongful idealization of eating disorders, she doesn’t understand how individuals could wish their painful experience on others.

“It makes me sick, and it makes me sad because there’s just a lot of your life that you can’t live when you’re going through an eating disorder and you don’t realize that you’re not living it. You don’t realize because you don’t even have enough brain power,” Freyermuth said. “I look back on it now, and I think about how rich and full my life is now compared to the emptiness it had when I was struggling with anorexia. It makes me so sad because there are so many people that don’t have that and instead of people encouraging them to try to get healthy and live life to the fullest they’re basically telling others ‘No, stay where you are. This is where you should be.’”

Freyermuth said if her doctor had shown concern at her first appointment, she might have realized sooner that she needed to get help and get better. She said when people agreed with her opinion, it only reinforced it, making her more steadfast in her behaviors. Seeing Pro Anorexia and Pro Bulimia sites, she said, could encourage people that eating disorders are ok.

Additionally, Weaver said not addressing the social emotional needs of any learner presents tremendous costs. These costs may present themselves in a number of ways including body image, anxiety, self-esteem issues and unhealthy relationships.

“If particularly a girl has the skills to do really really well in school then the mythology goes she must also have all the tools to be healthy and happy, which is why this is such an under-served group in terms of social and emotional needs,” Weaver said. Weaver works with girls to support social emotion learning by focusing on “self-confidence, goal setting, balance, compassion, kindness to yourself, and self care kinds of things.”

To provide support for these social and emotional needs, Weaver worked with guidance to establish an empowering young women’s group. For the past five years, this group has been open to high achieving junior girls. Weaver said initial student feedback was very positive; the group enabled them to make positive relationships with like-minded peers.

Seeing this gap in support for all students beyond the academic scope, Weaver said by not addressing the social emotional needs of any learner presents tremendous costs, which present themselves in a number of ways including body image, self-esteem issues and unhealthy relationships. Weaver said in her position as a gifted educator in particular, she sees a lot of perfectionist tendencies that, for a variety of reasons, tend to be more pervasive in girls.

“Often times in school we reward perfectionism … then there’s this pressure that comes along with all of this messaging, and I think that pressure gets tied too often to our worth as people and because it’s being reinforced so often,” Weaver said. “If unaddressed there’s that cost again of, ‘Well I’m taking eight AP classes. I speak three languages. I play two instruments. I’m doing varsity sports, and I feel this need to do all of these things ‘perfectly’, and there’s certainly no time left then right to form friendships, to cultivate hobbies that I do just for fun, to laugh, to get enough sleep, to eat well and no one’s telling me that those things are important.”

Without a program to teach these skills and to stress the value of self-care, Weaver said, our focus on perfection can lead to personal health issues. Living in a society with such reward for perfection, Freyermuth said she feels like it’s such a human thing, especially in the teenage years, to hide flaws. Everybody wants to pretend that everything’s great, she said, and nobody wants to let anyone else see that they are doing anything wrong. Although she believes nobody is perfect all the time, she said it is hard to admit to imperfections, especially for those with mental health issues because there are such stigmas on mental health problems.

Additionally, Freyermuth said people think of eating disorders as “Rich, stuck up girl, vanity problems.” However, Freyermuth said eating disorders can happen to any socioeconomic, gender, race or personality; it is not a one dimensional disorder. Overall, she said society needs to be more educated on eating disorders and how to deal with them. The stigma and behavior that people act with towards eating disordered people now is only causing those with eating disorders to recede further into their shells, she said, and their fear of judgement prohibits them from getting the help they deserve.

“There are still people who believe that mental health isn’t a real thing, and there’s still people that, even if they do know that it’s a real thing, get kind of freaked out by it. I’ve learned it’s a taboo subjects that most don’t really want to talk about,” Freyermuth said. “I think that that’s probably one of the reasons that sometimes eating disorders escalate so quickly. People that are going through it feel like they have no one to talk to and anorexia is such an exclusionary disease because not only do you feel like you can’t tell anyone what’s going on because you’re embarrassed and you’re worried of the stigma … Your brain starts to shut down and your body starts to shut down and soon enough you’re really alone, and that isn’t what you wanted.”

“Often times in school we reward perfectionism,” Weaver said. “Then there’s this pressure that comes along with all of this messaging, and I think that pressure gets tied too often to our worth as people.”

Beyond misinformed assumptions about eating disorders in society, misunderstandings within families and friend groups can weaken support during recovery. Parker said family and friends need to be educated and know what the eating disorder is and how to handle it, but they also need to avoid policing a recovering individual.

“Often I think in families the eating disorder begins to emerge as a thing that sort of dominates the whole family, so it’s really important that family members see the their family member with an eating disorder as not an eating disorder with two legs, but ‘Hey this is my daughter. This is my sister,’” Parker said. They “still like the same things they always did, so getting in touch with ongoing goals and hopes and dreams is really important for family to do.”

In retrospect, Freyermuth said society’s stigma on eating disorders slowed down her recovery and increased her sense of isolation. As a lifetime perfectionist, she said she was afraid to admit that something was wrong. While she initially found it easy to talk about her eating disorder, she said she also felt separate from that part of her life, so admitting it was like admitting someone else had a problem. Even with such support from her friends, it became harder to tell people what she had been through as she started connecting herself to her eating disorder.

“I’m sure I had people that judged me and I’m sure that people reading this article are going to judge me, too, because so many view anorexia as an ‘attention-getting disease.’ That is not what it is at all. Some people may think, ‘Oh, that’s not a real thing. She’s just making crap up,’ and the thing is that I’m OK with having people say that about me if I know that me doing this is going to help at least one other person who’s going through an eating disorder feel comfortable admitting it,” Freyermuth said. “If you hide your whole life from something that happened to you because one or two people don’t respect it then you can’t help the other people that are going through it.”

In the future, Freyermuth wants to major in English and either political science or film. After college, she wants to join the peace corps. No matter what she decides on, she said, she wants to use her skills to work with mental health advocacy.

“I love hearing peoples stories and I love seeing peoples relief and animation as they tell the stories they’ve long had to hold inside. After I get a degree in writing and political science or film I would love to get to meet with people continue to tell their stories using the skills that I gained from my college education. I want to enact change, lawfully and societally, so that those struggling with eating disorders don’t have to fight the stigma of others as they are dealing with fighting their mind and body. If I did something with film I could do documentaries on that, with political science I could enact policy changes. Struggling with anorexia nervosa and hearing others stories has definitely given me a passion for getting out awareness, tolerance and acceptance for mental health among people.”

By Emily Franke

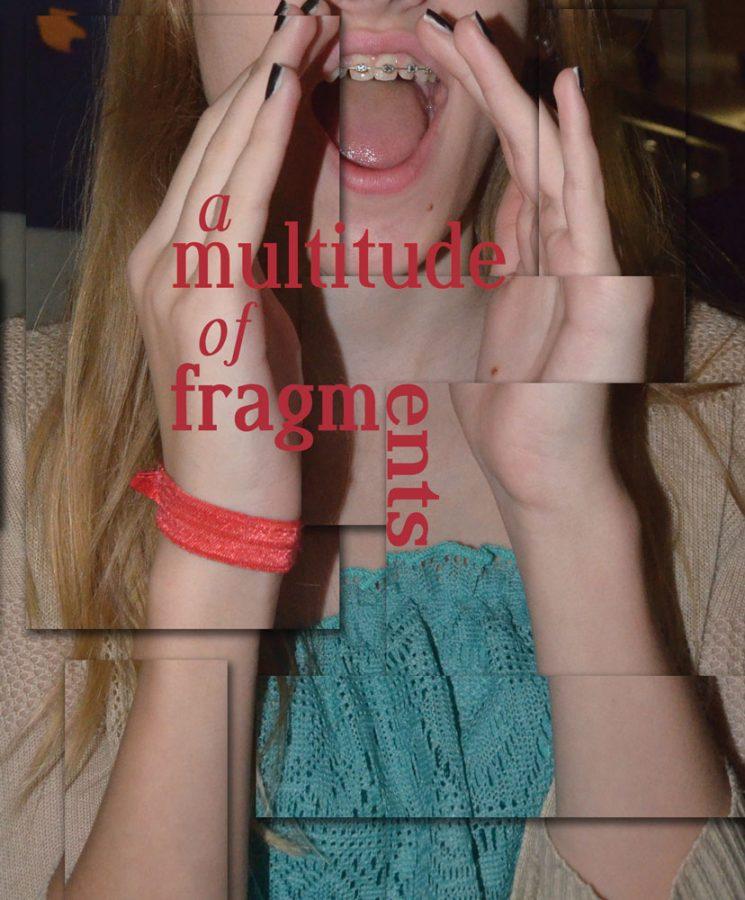

Photo illustrations by Sury Rawat