As we climbed the stairs from the transit and anticipated the warm California air, he greeted us — a warm smile and dark, chocolate skin stretched thin over his cheek bones.

“Why hello there!” he said, holding his bright smile and my attention. “They call me the best-dressed homeless man in San Francisco.”

My muscles instantly tensed, and I fought the urge to fetch my $200 phone from my side pocket and secure it between my palms.

He didn’t look homeless. He wore cargo pants, a few layers on top and a hat, but when this man titled himself as “homeless,” my first impression of him swiftly changed from a friendly welcomer to a scandalous beggar and low-life con-man scheming to take my money and belongings. I couldn’t help it; I have been trained to think this way.

The abundance of this new foreign breed was a shock when entering the heart of this bustling town. Even before being able to admire the three stories of a glorious Forever 21, my eyes couldn’t help but first dart to the woman lying in front of the doors on the ground, her feet bare and blackened from long trips up and down the cracked and rough pavement, no doubt shaking a can with a few pennies to any passerby. If it wasn’t for the slight up and down movement of her body when she would occasionally take a breath, you could barely tell that she was alive.

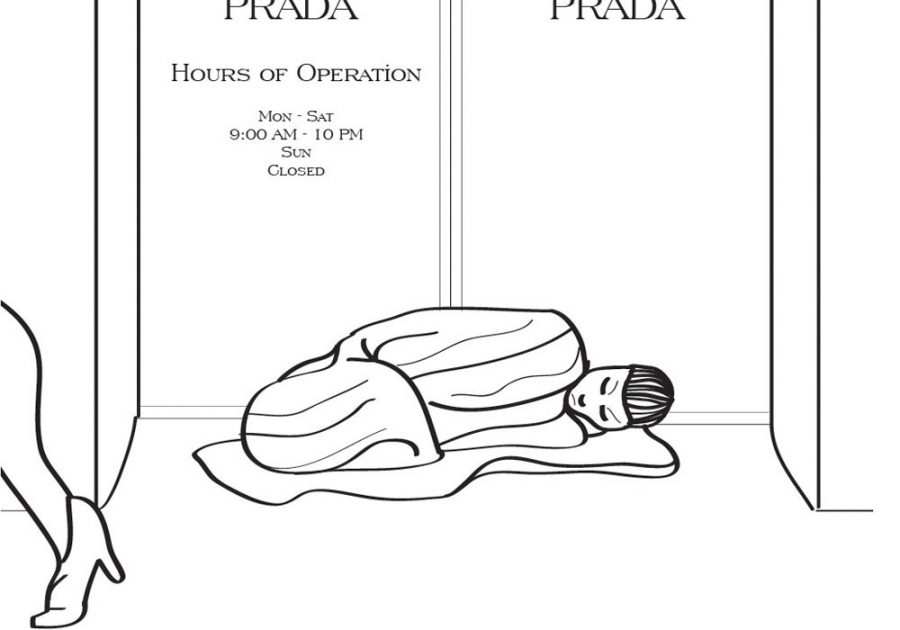

Although they usually ask for spare change during the day and hold cardboard signs on sidewalks and street corners, what’s worse is seeing them drift into slumber against light poles. Before seven, Union Square, one of the richest parts of San Francisco, fills with plastic, made-up faces and stilettos, while the night scene crawls with the hungry and helpless curling up on the marble, polished steps of Burberry and Prada.

After just being here for two days already, I have had to censor my mind to these people. Mom always said to never give them money — they will always abuse it or buy things that hurt them even more, but is this responsibility to give to the less fortunate now discarded? I have two extra bedrooms in the house I live in, I eat when I’m not hungry, I sleep in a bed made for two people, and I can’t decide what to wear in the morning because there is too much to choose from.

I have to pretend I don’t hear their cries or even that I don’t care. I convince myself they are acting the part or that someone else will give them money when, in reality, I am kidding myself. They are the less fortunate and the disabled, the worn and weary. They are people, living a life I hope to never turn to but just might have to if tragedy strikes.

I lied to a woman I didn’t know this morning. She saw me across the street and ran to meet me, and without even knowing her name, I lied to her. I assume I already know her story — she’s a good actress, she has money, and she just wants to play me.

“Will you please give to an old homeless woman?” she pried, clasping her hands together as if she was praying to ask God. “Please — Anything. Will you please help me?”

But I don’t know her story, nor did I want to know, because the truth could possibly make me show sympathy in light of my selfish nature. I told her I didn’t have any money as I clutched a Subway breakfast sandwich and coffee. I lied to her. And without a second thought, I walked on with a full wallet and a cold heart.

If I get the chance to meet this woman again, I would take her to dinner and sit with an open mind and ears. I want to know these people and view them as more than beggars and a nuisance. I want to think of them as human beings with histories, families and lives — which might just put them on the same level as any one of us.

By Kaitlyn Marsh