Opportunity

This special report on OPPORTUNITY covers

the difference between determinism and determination,

how students who live thousands of miles away from parents cope

and the pressure on second generation immigrants to succeed.

Immigrants’ kids feel pressure

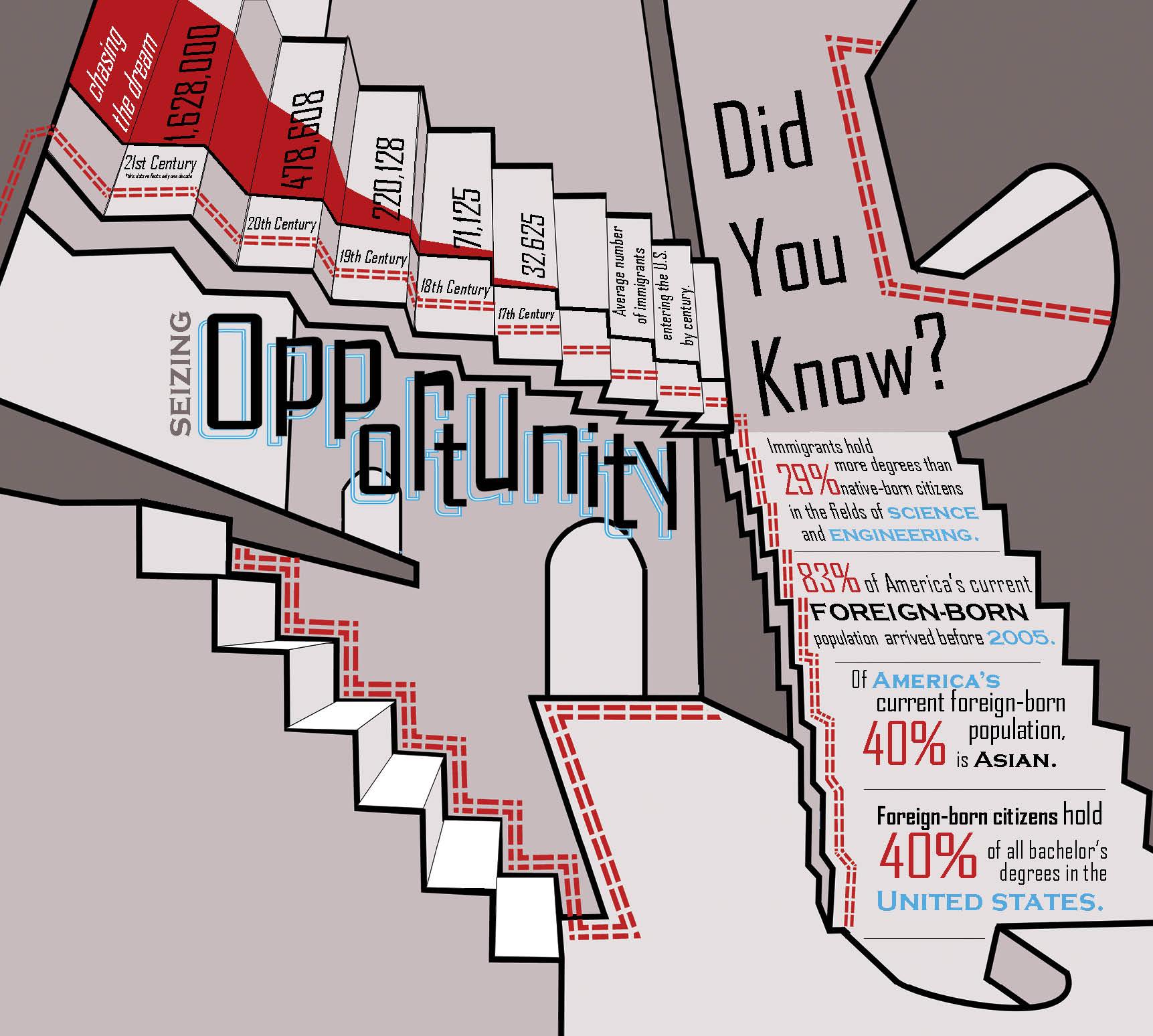

The black and white images of dirty children, women wrapped in shawls and men holding on to suitcases fill the history of America. In fact, this country’s coined nickname is “the great American melting pot,” referencing the steady flow of immigrants who established this country’s diverse cultural atmosphere.

The black and white images of dirty children, women wrapped in shawls and men holding on to suitcases fill the history of America. In fact, this country’s coined nickname is “the great American melting pot,” referencing the steady flow of immigrants who established this country’s diverse cultural atmosphere.

For many immigrants coming to the United States means providing more opportunities to their children. Immigrants leave their home countries behind, battling a new language, cultural changes and difficult jobs to provide better futures for their children.

Junior Mary Claire Sarafianos grew up hearing horror stories about immigrants’ poverty; her grandparents left Cairo, Egypt with only the money they could sew in her grandmother’s dresses and fled to Greece, where they raised Sarafianos’ father. Later, he moved to the United States for the same reason as his parents did, hoping for better opportunities for his children.

These stories, well worn with re-tellings, became the motivation for Sarafianos’ hard work in school and the measuring stick for her accomplishments. Her family is not alone. According to the Census Bureau’s 2009 American Community Survey, 12.5 percent of America’s population is made up of immigrants.

“It’s kind of like a math problem. They started out with so much less and still succeeded,” Sarafianos said. “I feel like I must succeed even more because I started out with more.”

Sarafianos said she pushes herself in school because she wants to honor the sacrifice made by her father. Sarafianos’ father encourages her dedication to education, sending her dozens of emails about scholarships, Saturday Morning Science and ACT or SAT preparatory classes.

“I’m very serious about my education,” Sarafianos said. “When I get an A on a test, it makes my dad so proud; he tells everyone in the lab he works at.”

Her father instilled important values in her, believing these would make Sarafianos successful in this land of plenty. He mainly stresses the importance of education and prudence; money is a resource that, like opportunities, should not be wasted or casually dispensed.

“He’s big on frugality,” Sarafianos said “When [his family] moved they were dirt poor but started a business, became successful and have been hell-bent on being money-smart ever since. [Because of him], I’m serious about my education, and I’m a lot more thrifty than most kids.”

Saving money and thereby creating security for their children is many immigrants’ main priority. They believe financial security will open more doors in their children’s futures. Nearly a quarter of immigrant families, according to the same survey, classify as “middle class.”

Junior Lily Qian said her parents, who emigrated to the U.S. from China, value money more than most parents.

Her dad “came from a poor farming family, and he gained a lot more opportunities here,” Qian said. “Because both of my parents didn’t come from the wealthiest families, and they know what money is worth, they tend to prefer saving over spending, and they always shop for sales, even up to pennies’ worth.”

Similarly, senior Maria Ramirez’s parents moved from Guatemala when she was two. Like Sarafianos, Ramirez’s family places importance on education and money. Ramirez said her parents value education because they lived with fewer opportunities as kids.

“Guatemala is poor and has little to no opportunities for a successful life,” Ramirez said. “I have to study during the weekends, even when there are not tests because [her parents] know what it is like not to have hope for the future. If there’s opportunity, take it.”

But the stress put on second-generation immigrants by their parents may be too great. Sophomore Inas Syed said when her father moved to America from India, he had to work many hours at a challenging job in addition to taking classes at a university.

“When my dad came over, he had very little. … So for me although he pushes me to work hard and get good grades, he doesn’t want me to stress because he knows how hard it was,” Syed said. “He has given me the ability to succeed without pushing myself as hard as he did.”

Ramirez sometimes feels the same kind of stress that Syed’s father tries to protect her from. Ramirez said although she usually appreciates the motivation from her parents, sometimes it feels like a “monkey on my back.”

Sarafianos seconded the idea, saying although she cares for her father and knows he is trying to help her, she can’t help but be worn out from the pressure some days, especially when both girls said they see their American friends at school not valuing the opportunities given to them.

Sarafianos’ mother, Mary Sarafianos, who is American, said the stress second-generation immigrants feel is self-inflicted. After many years of hearing tragic immigration stories built on work ethic and sweat, the students believe their parents want them to emulate that, when all they want is for their children to be successful and happy — the same as any other parent.

“When the image of their parents’ stories about how hard it was to get here combines with the American dream they learn of in school,” Mary Sarafianos said, “it exaggerates their need to fulfill their parents’ wishes, to honor the sacrifice.”

Unlike Mary Claire Sarafianos, junior Eric Cropp, whose mother is Japanese, said he does not feel the pressure many second-generation immigrants see. He cites the reasoning as his self motivation. This motivation to do well comes not from an immigrant’s guilt but from a want to succeed himself.

“I try to do whatever is good but not for my parents,” Cropp said. “I don’t honor my parents by achieving. It’s a lot of pressure second-generation immigrants put on themselves.”

Whether parents induce the pressure or second-generation immigrants create it themselves, this motivation to value education, money and opportunity creates a new spice in this big and strange melting pot of a place.

“Coming from a third world country, you’ve seen poverty and sickness,” Ramirez said. “You appreciate and work for what you’ve got.”

By Maria Kalaitzandonakes

Minors exchange parental security for freedom

After taking a 14-hour flight and traveling 7,000 miles, sophomore Hyo-Eun Kang arrived in the United States alone. She had left her parents behind in Korea to live with her older sister, a student at the University of Missouri—Columbia.

It would be more than a year before she saw either of her parents again.

Kang is one of the five percent of Missouri residents under the age of 18 who, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, live alone or with only siblings. For these students their lifestyles are a sacrifice. Stress, solitude and a huge increase in responsibility accompany any student who opts to live alone.

“My initial thought was, ‘This is not right. I’ve made a mistake, and I can’t bear the loneliness,’” Kang said. “Now that I’m adjusting more to the environment, I think it’s better because in terms of my future there’s more opportunities, and I feel very fortunate to take a stab at it.”

Kang’s migration to the United States embodies a larger movement in Korea where many students are spending their high school years abroad in order to receive a higher quality, yet less intense, education.

In Korea Kang attended four “cram schools,” private schools that focus on a single subject with the promise of raising test scores and chances of college entrance, in addition to a regular high school. Daily she did not return home until 10 p.m. and usually stayed up until two a.m. working on homework. Even though Kang says this was normal for Korean students, her parents decided to send her to the United States for a better education.

“In Korea everything is almost forced,” Kang said. “It’s required, and it’s very hard because so many people are talented there. So many people work so hard, so to be one of the best there, [it] is much harder than to work hard here.”

Senior Alex Sun moved to the United States from Taiwan in seventh grade. His mother stayed with him and his younger brother and sister, one and three years younger than Sun, respectively, but moved away Sun’s freshman year while he lived with a guardian. Eventually disagreements with his guardian reached a point that Sun moved into a separate condo to live with his two younger siblings without an adult.

The added independence, as well as the more individualistic culture of the United States, has opened up the possibility of a lifestyle Sun said he couldn’t have in Taiwan. He told his parents he was homosexual his freshman year, something he said he wouldn’t have done outside of the United States until college. Although Sun was excited to be honest with his parents about who he was, the contentment was short-lived. Sun didn’t believe he could have a family and be gay. The idea of spending his life alone dampened his spirits. It wasn’t until he saw a video on YouTube about the lifestyle of a family with same-sex parents the summer before his junior year that Sun said he realized new possibilities for his future.

“I always thought I was going to end up alone. I’d probably end up with my parents,” Sun said. The video “made me feel like I could have the life that my parents had, and I could have a family, and I could be very happy.”

But living without parents has also made Sun the sole caretaker of his younger siblings. He’s responsible for paying bills, grocery shopping and solving problems. For instance, last semester his condo flooded the weekend before finals week. He and his siblings slept in shifts for three nights, taking turns sucking up excess water with a SteamVac. For Sun experiences such as this highlight the advantages of attending the University of Missouri—Columbia, making it easier to take care of his younger siblings. But he isn’t ready to turn down more prestigious institutions.

“Sometimes I fear that I won’t be able to live like a teenager. I’ll just be a parent,” Sun said. “Am I required to sacrifice my life for my siblings just so things can be easier? I don’t know. I wish I could just say, ‘I don’t care.’ My parents keep telling me that I should chase my dreams, and I shouldn’t hold back and that whatever happens, happens. But sometimes it’s really hard.”

Despite the challenges and uncertainties looming in the future, Sun said he prefers his life in the United States to how he probably would have lived in Taiwan; in fact, this lifestyle has changed him.

“A lot of who I am now has to do with this position and I wouldn’t say it’s everything that I am, but it’s part of me. It’s really hard to say that [living in the United States] is worth it or not,” Sun said. “I would imagine I would be a much different person, and as I am now I would say it is worth it to make the move from Taiwan.”

Not all students who live alone, however, are searching for a better education or trying to change their lives. Rather than moving to a new high school, senior Nici Thaler decided to stay in Columbia after her father took a job in New York right before her junior year. Thaler’s mom traveled back and forth between New York and Missouri. At first her mom spent most of her time with Thaler in Columbia, but eventually Thaler said she spent as much time as a month alone.

“There are times where I wished they were still here and I didn’t have the responsibilities I have,” Thaler said. “But in another way it kind of helped me grow, and it kind of readied me for college.”

At the beginning of her senior year, Thaler’s dad moved to another new job in Connecticut. Her mother moved to stay with her father permanently, and Thaler went to stay with family friends. Even though she was living with two adults, Thaler said she still faced some challenges by herself.

“There was a point while I was applying to colleges where I was like, ‘I cannot do this,’” Thaler said. “But I talked to my mom, and I talked to friends, too, and everyone was really supportive of it, so I got through it.”

As Thaler and Sun prepare for college, Kang will spend two more years living with her sister before she decides to move on to higher education, either in the United States or in Korea. But she has already learned an important lesson from living alone.

“I think I matured because back in Korea my mother was always there to do the cooking, the laundry – all that necessary housework,” Kang said. “This really made me more appreciative of my mother’s position as well as stronger and bolder because now I know that responsibility is not a choice, it’s a must.”

By Jack Schoelz

additional reporting by Kirsten Buchanan

interviews with Hyo-Eun Kang were translated with assistance from Joanne Lee

Determinism vs. Determination:

Debate sparks from unanswerable questions

A steering wheel, it is fair to say, is considered a common object. Most Americans use it at least once a day, whether driving themselves or sitting along for the ride.

Like in real life, the steering wheel allows the driver to go the direction he chooses, as he selects which twists and turns will be most beneficial to his journey. But is it all up to the driver? Or are other unknown factors responsible for the outcome, something like fate?

This age-old question, whether free will or fate determines the path of the human races’ lives, classifies as one of the many puzzles yet to be solved.

For sophomore Megan Kelly, this question affects the journey to her dream. She idolizes spending her life performing. In her perfect world, she would be a star on Broadway. She has had this dream for her entire life, working toward it by participating in theater since the age of six. Most of the opportunities depend upon whether or not directors like her, but she concludes hard work is the true decider. To help with her impressions on these people, she improves her skills as much as she can.

“With auditioning for things and asking people for help on working on singing and dancing and acting … it’s not going to just happen to me if I just sit around and don’t try to improve and try to audition for things,” Kelly said. “But at the same time … I can’t change my future. I can try, but I’m not fully in control.”

Still, Kelly takes responsibility for as everything in her ability. From networking to auditioning for as many productions as she can, Kelly grabs her dream for herself. She said nothing will happen if she waits for it to come to her.

Those who believe in the merits of hard work and free will find comfort in having complete power to make choices. Rockford University Associate Professor of Philosophy Matthew Flamm, Ph.D., said followers of free will benefit from knowing what to expect from life, rather than anticipating life-altering turns.

“Free will is appealing for the very obvious fact that it means our direct choices can alter the course of events,” Flamm said in an e-mail interview. “If fate decides our opportunities … we can simply relax and let things happen as we might interpret them to have been ‘meant’ to happen.”

This principle of fate greatly appeals to some. Whether it gives people fast security in knowing they have a set life already planned out for them or allows them to sit back and let life come to them with a fuller swing, fate can be a great comfort for many, including junior Rasheeq Nizam.

Both of Nizam’s parents are doctors, so it seemed logical for him as a little kid to follow in their footsteps. Now that he is old enough to understand what becoming a doctor entails, he has decided to pursue the career. He does not have his future fixedly planned, and his belief in a higher power may steer him in a different direction than the one he envisions for himself right now. Nizam feels even if he works for something, it will not happen if God did not have it in his plans.

“Things are in God’s control, so whatever happens is because God decided that it should happen,” Nizam said. “But it’s also based on what you do. If you never do anything, then nothing will happen.”

This belief and Nizam’s knowledge that some things are out of his control lead his life with purpose. Even if he doesn’t feel what happens to him may be in his best interests, he must trust that God has a plan and knows what will benefit him the most.

In general, more religious people “put their entire faith in something beyond themselves,” Flamm said. “When things happen to them, good or ill, they retrospectively assign some ‘predestinating’ reason for it.”

However, many do not go to the extreme of one side of the debate or the other. They follow both free will and fate. Even though Kelly tries to make her dream a reality, she knows some factors of her life simply reach beyond the choices she makes.

Life is about “fate and opportunity and how you take control of the opportunities you have,” Kelly said.

She lives with both fate and free choice, the two affecting the journey of her life.

Despite his efforts to help his life takes the turns he wants it to, Nizam knows some things are out of his power. He accepts that a higher power has mapped out a journey for his life, and he has to just let it come to him.

“It sort of boils down to that,” Nizam said, “moving on from things that didn’t happen, with the knowledge that God knows what’s best for you.”

By Maddie Magruder