Religion provides reason for the unexplainable in post-World War II science fiction

September 27, 2022

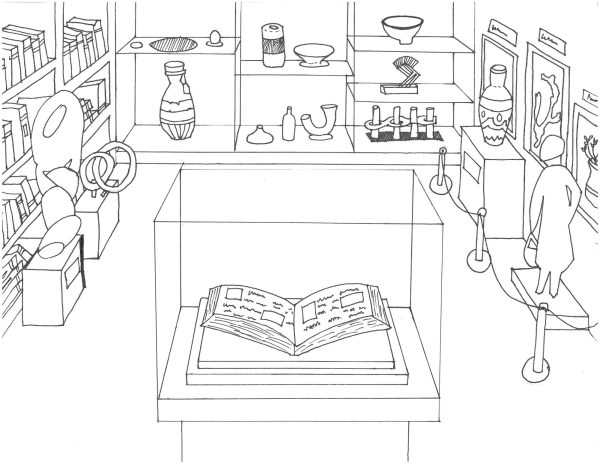

The defeated pylon stood disarmed in the vast, charred desert of the frontier planet. The Vault hidden underneath it had sent exigent beams of radioactivity toward the spaceship, unabashedly leading it to the remnants of intelligent life on the long-forgotten planet. This strategically placed structure laid out generations worth of treasures for the astrophysicists: thousands of visual records of their existence, books brimming with ancient text and pictures of cities much grander than any man had created on Earth. As the men absorbed 6,000 years of unconscious history, they watched scenes of children laughing on beaches of blue sand, wondering what made that faraway star go from providing the civilization warmth and life to suddenly obliterating its serenity. The supernova decimated the entire population of that little, prosperous world at its peak; even if God has no need to justify His actions, for what merciful reason was life not given the chance to flower? Was their destruction really essential for the bursting star to become the shining guide on that fateful night in Bethlehem?

Published in Nov. 1955, “The Star” by Arthur C. Clarke follows the journey of a Jesuit astrophysicist to a white dwarf subject of a supernova. The main character believes that space could not undermine his faith and would instead reinforce it by exemplifying God’s handiwork. His crew, though, quickly finds a planet orbiting the star that carries evidence of a past, flourishing intelligent life. The supernova upended the population, but it turns out that the light from the explosion was seen on Earth the same day the Three Wise Men walked from Jerusalem to Judea in search of the son of God. The undeserved extinction of the alien population left the main character faithless, no longer being able to justify the cruelty of the event. The exploration of inexplicit metaphysical allegory is abundant in post-World War II science fiction like Paul Payne’s “Fool’s Errand” (1952) and Walter Miller Jr. ‘s “A Canticle for Leibowitz” (1959), indicating a return to religion triggered by the irredeemable loss of life during the world wars. This inspection of the unexplainable was fostered through the possibilities of space.

The supernova decimated the entire population of that little, prosperous world at its peak; even if God has no need to justify His actions, for what merciful reason was life not given the chance to flower?

Before the world wars, theological discussions in science fiction primarily focused on made-up religions or reinforced already existing ones. In “The Wonderful Visit” by H. G. Wells (1895), an angel is brought to Earth to “observe the sins of mankind,” while Jean Delaire’s “Around a Distant Star” (1904) describes space voyages that justify Christian doctrines. Many existing religions were not questioned in literature in the 19th century and prior, and extraterrestrial religions were actually regarded as foolish in science fiction stories in hopes of reinforcing the author’s own spiritual beliefs. On the other hand, stories after World War II immersed themselves in theological thought and approached alien religions with an air of openness.

World War II destroyed swaths of land, killed 80 million people (4% of the global population), redrew boundaries and introduced the atom bomb — nations could now annihilate the entire human race. During the war itself, factors that increased religiosity such as marriage and participation in Church decreased because of a strain on resources and, in all reality, people. Starting in the 1950s, though, the economy prospered in America, and the baby boom ensued. The onset of the cold war also led to Western (America in particular) adhesion to Christianity as an effort to differentiate themselves from the “atheistic communism” of the Soviet Union, adding “under God” to the pledge of allegiance in 1954. A shift toward traditional values was also seen in science fiction, but the mindset of authors did not change; the uncertainty of humankind’s fate after witnessing the cruelty of World War II placed metaphysical speculation at the forefront of their writing process. How can God justify the pain of the post-World War II world, and how can society proceed to understand it?

In his short story “—and the Moon Be Still as Bright” from “The Martian Chronicles” (1950), Ray Bradbury describes the events following a rocket landing on Mars. The nearby Martian civilization died out thousands of years ago, but the cities remain “flawlessly intact.” Jeff Spender, one of the archaeologists present on the trip, is afraid of what humans will do to the abandoned, ancient landscape once commercial interests overpower restoration efforts. He ends up shooting five crewmates in response to his fear, and a manhunt ensues. In a conversation with the captain of the space crew, he reveals certain epiphanies he has after studying Martian life: “The animal does not question life. It lives. Its very reason for living is life; it enjoys and relishes life,” and “They [the Martians] blended religion and art and science because, at base, science is no more than an investigation of a miracle we can never explain, and art is an interpretation of that miracle.” He explains to the captain that, after some period of war or despair, there was no answer to the question, “Why live at all?” Martians learned that the answer to this question was that life was inherently good.

At the end of this story, the captain shoots Spender, and the “last Martian” dies. The main idea of this story is not religion, but while searching for the meaning of life in its text, religion is eventually discussed. It is not glorified or romanticized but is shown to be an essential aspect of existence that should not be ignored in response to an influx of human suffering or empirical notions. World War II is humankind’s equivalent to the period of conflict the Martians went through, and Bradbury’s supposed theory on how to react to it includes treating the clashing ideas of science, religion and art with impartial respect in order to bring society to the point where the question, “Why live at all?” is nonsensical.

Bradbury, in another short story, “The Fire Balloons” from “The Illustrated Man” (1951), talks about the journey of a group of pastors led by Father Joseph Daniel Peregrine to a human settlement on Mars. Peregrine hopes to eliminate all sin on Mars, not knowing whether the foreign world would present sin straightforwardly as virtue or as something else entirely. When he reaches Mars, he hears of blue orbs living in the mountains and leaves to spread the word of God to them. To his surprise, they turned out to be devoid of sin ever since they freed themselves of their physical bodies and learned to live in God’s grace. Peregrine learned from the alien life, not the other way around.

World War II is humankind’s equivalent to the period of conflict the Martians went through, and Bradbury’s supposed theory on how to react to it includes treating the clashing ideas of science, religion and art with impartial respect in order to bring society to the point where the question, “Why live at all?” is nonsensical.

Reminiscent of “— and the Moon Be Still as Bright,” the Martian civilization in “The Fire Balloons” is shown to be thousands of years wiser than its human counterpart and transcendent of Earthly dilemmas. Once again, the acceptance of religion in society is seen as immensely beneficial for all life, but humankind is never the society adopting it in the stories.

Throughout these stories, religion is discussed without mockery; it is taken seriously. Spender’s explanation for why he killed his fellow crewmates has reason. Peregrine’s fear of sin presenting itself in unprecedented forms is shared. Even the inexplicable blue, floating orbs on Mars make enough sense to cause a learned theologian to get on his knees. The loss of life seen in World War II is greater than any other war before it and is difficult to justify or ignore, so science fiction writers tried to reason with it. Using vivid otherworldly lands, disparate civilizations and deep space as scenes for their speculations, authors wrestled with philosophical ideas for the chance that some glimmer of insight would appear in their stories. The epiphanies are numerous in quantity and continue to pile up as new, timely issues arise. After all, there is still no answer to why that inconspicuous civilization had to die on that fateful night in Bethlehem.

What is religion’s role in science fiction? Let us know in the comments below.

wamp • Oct 3, 2022 at 9:37 am

AYO GREAT ARTICLE 10/10 WOULD READ AGAIN!

wamp • Oct 3, 2022 at 9:37 am

AYO GREAT ARTICLE 10/10 WOULD READ AGAIN